Uranium Update: Going Nuclear!

The reasons for uranium’s spectacular ascent, demand-supply factors, and the prospect for a secular bull market

This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

Uranium is the best-performing commodity of 2023, with the spot price up +50% in the first nine months of the year. September itself proved to be a banner month, with the U3O8 spot price rising from US ~$60/lb to US ~$72/lb over 30 days.

What has caused the price of uranium to rise so dramatically in 2023? This year, investment vehicles have not been particularly active in purchasing U3O8,1 and so have not been a major factor in driving up the price. Rather, we think that investors and utilities have started to come round to our longstanding view2 that the world is facing a large uranium supply deficit for the foreseeable future.

Despite the price increase, current uranium prices are only just reaching the incentive price required to restart a handful of second-tier brownfield production assets. Even higher prices will be needed to incentivise the development of other tier-two and tier-three brownfield assets, not to mention the greenfield production which will be required to meet even the modest base case for demand growth in coming years.

In recent months, there has been increasingly bullish news for uranium from the perspective of both demand and supply. The rapidly rising U3O8 spot price is the most obvious gauge of these improving market dynamics. Our recent conversations with uranium buyers also indicate that the market is extremely tight; it is hard to purchase even a few million lbs of U3O8 without paying substantially higher prices.

Below, we summarise some of the recent demand and supply headlines for uranium.3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Demand Factors

The utility contracting cycle for uranium has finally started.4 UxC reported ~114mn lb of contracts signed by utilities in 2022 (compared to ~72mn lb of contracts signed in 2021). So far in 2023, ~120mn lb of contracts have been signed. Despite the rapid growth, it is still early in the cycle and utilities are not yet signing contracts at a pace which would meet the replacement rate for their contracts which are rolling off.

In May, Italy announced that it would reverse its 1987 moratorium on nuclear power and consider reintroducing nuclear energy into the country’s power mix.

In June, Électricité de France was delisted as the French government completed its nationalisation of the operator of the country’s fleet of 56 ageing nuclear reactors. This allows the French government to accelerate its plans to extend the lives of existing reactors, as well as provide government funding to build a further 6-14 new reactors.

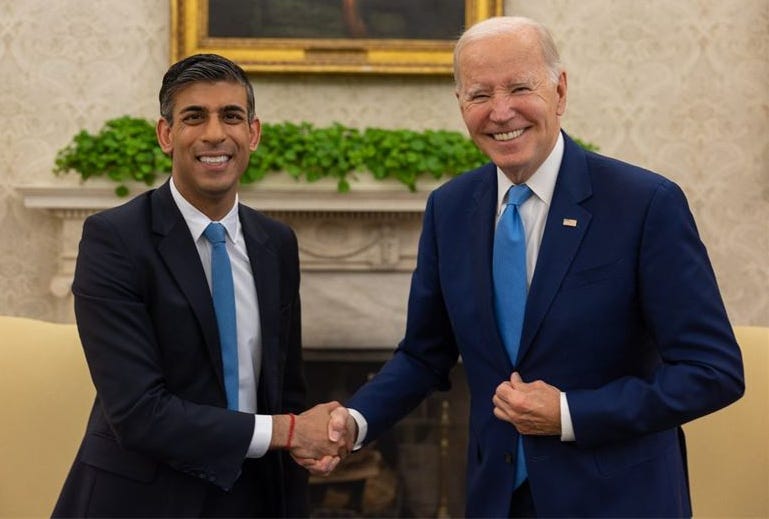

Also in June, the US and the UK signed the Atlantic Declaration for a 21st Century US-UK Economic Partnership. This includes a civil nuclear partnership, which plans to create full nuclear fuel-cycle capabilities in both countries by 2030, as well as the development of new technologies such as Small Modular Reactors (‘SMRs’). Funding will also be made available to meet these objectives.

In July, Belgium committed to reverse its policy of exiting nuclear power by 2025, building on its decision earlier this year to extend the life of two reactors which are currently not in operation. Belgium is an interesting example of the shift of opinion regarding nuclear power in Europe, due to rising concern over climate change as well as worries over energy security following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

In July, Kansai Electric Power in Japan restarted its Takahama 1 nuclear reactor, followed by the Takahama 2 nuclear reactor in September. Japan now has 12 reactors in operation.

Also in July, President Yoon of Korea publicly mulled adding further nuclear power plants to the Korean power mix. This was on top of his commitment last year to reverse his predecessor’s policy of phasing out nuclear power.

At the end of July, China approved six new nuclear power plants to be built in Fujian, Shandong and Liaoning.

In August, it was reported that Saudi Arabia is considering offers to develop nuclear power from France, Russia and China. This is apparently in an effort to increase pressure on the US to reach an agreement; as part of the deal, Saudi Arabia is requesting that it be permitted to enrich its own uranium domestically, which the US is reportedly resisting.

The Middle East is already an important growth area for nuclear power. The United Arab Emirates started generating nuclear power in 2020 at the Barakah nuclear power plant, and in January this year the UAE signed a memorandum with Korea to further boost nuclear cooperation and expand the UAE’s reactor fleet.

In August, seven countries announced the formation of the International Bank for Nuclear Infrastructure (‘IBNI’).5 IBNI is a multilateral organisation which will provide financing for the development of civil nuclear power; a lack of financing has been a major constraint on building up the industry. A joint declaration is due to be signed later this year at the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP28).

Also in August, Sweden made the somewhat surprising announcement that it proposes to build ten new nuclear reactors by 2045. This builds on recent decisions in Sweden to restart two idled reactors and remove the country’s longstanding cap of ten reactors.

In late August, Frederick Merz, the leader of the CDU (Germany’s largest political party, currently in opposition) announced that if he were leading the country, he would “immediately reconnect decommissioned power plants”. This raises the prospect of a potential future political reversal on nuclear power in Germany too.

In early September, the World Nuclear Association (‘WNA’) held its annual jamboree in London, which was widely reported to be the WNA’s most bullish symposium in decades. As part of the event, the WNA released its biannual Nuclear Fuel Report. The WNA’s demand projections to 2030 are approximately in line with our estimates and with the WNA’s report from two years ago.6 From 2030, however, the WNA’s projected U3O8 demand growth rate more than doubles to 4.4% per annum.

The WNA’s major driver of projected demand growth in the 2030s is the rollout of Small Modular Reactors. This technology now seems set for commercialisation from the late 2020s. If SMRs do take off successfully, this raises the prospect of a secular bull market in uranium rather than just a cyclical upswing.

Recent positive news flow for SMRs includes: Finnish energy company Fortum signing an MOU with Westinghouse in June to investigate deploying SMRs; reports that Microsoft is looking to SMRs to power its data centres; and the Kingdom of Jordan announcing that it plans to use SMRs to power a water desalination plant.

Supply Factors

In mid-July, ASX-listed Peninsula Energy, announced a substantial delay to its restart plans for its Lance Project in Wyoming. This project had been expected to go into production in the near future. It will now be necessary to accelerate in-house development of resin processing and yellowcake production rather than relying on a third-party. This requires substantial capital investment, however, and delays production significantly. Such news underscores the challenges faced by uranium miners as they attempt to start and ramp up production.

On 26 July, a coup d'état in Niger raised the prospect of a complete halt to uranium production and exports from the world’s sixth largest uranium-producing country for the foreseeable future. Niger accounts for ~5% of the global primary production of uranium, most of which goes to Europe (France and Spain). This also further complicates the geopolitical and energy calculus for European countries.

In an August update, Kazatomprom – the global lowest cost producer – revised its operating cost guidance higher by 5-8%. The company is also now guiding for 2023 cash costs as much as +40% higher than last year. This is a salient example of the cost pressures facing the industry, and why a higher incentive price will be necessary for more uranium projects to come to production.

In September, Cameco cut its full year production guidance by ~9% (~3mn lb). This is due to operational issues at the Cigar Lake and McArthur River mines and the Key Lake Mill. Part of the problem appears to be a lack of experienced workers – a common refrain in mining, and indeed apparently across all sectors and countries. This highlights the lack of talent in the industry and the difficult operating environment, even for experienced uranium producers.

In late September, Kazatomprom announced a higher-than-expected 2025 production target of ~80mn lb U3O8, an amount which would be ~+48% higher than 2023 production levels. This target includes production for existing assets as well as two new mines (Budenovskoye 6 & 7). The uranium market initially pulled back on this news, but then stabilised as investors realised that this new Kazakh uranium production likely already had a buyer lined up, given recent contracting deals signed with both Russia and China.

A larger than expected supply response from the world’s largest low-cost producer Kazatomprom remains one of the key risks to the uranium market in the short- to medium-term. It is thus an area that we continue to monitor. Nevertheless, we see a reasonable chance that Kazatomprom will miss its challenging new 2025 production targets given supply chain and operational challenges (e.g., procurement of sulfuric acid and other key equipment for ISL mining).

The ‘bear in the room’ when it comes to the uranium market is the issue of Russian supply.

While Russia is a relatively small producer of uranium itself, the major reliable route for exporting shipments of Kazakh uranium to the world has been via Russia, shipping out of St. Petersburg. Kazatomprom has developed an alternative route to western markets, although substantial challenges exist.

Even more importantly, Russia accounts for ~30% of global conversion and ~40% of global enrichment supply.

Western nuclear utilities are thus still very dependent on Russia, which explains why the US has not formally sanctioned the Russian nuclear complex (i.e., Rosatom and associated companies) in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, despite sanctions on most other sectors.

That said, numerous bills are now working their way through US Congress which seek to sanction Russian nuclear-related exports.7

Moreover, many Western utilities are already self-sanctioning, in other words they are taking deliveries from existing contracts, but not signing any new supply agreements involving Russia. This is in the expectation that they will only be permitted to procure uranium from “friendly” nations in the near future.8

In other words, owing to geopolitical factors, the world is rapidly heading towards a bifurcated uranium market. Note that a world with two uranium prices (for the West and for the Soviet Union) was the status quo before 2003, and we anticipate a return to this situation in the 2020s. This would mean much higher prices for uranium in the West. Uranium is thus effectively a call option on increasing geopolitical tensions.

In summary, developments in 2023 have been extremely bullish for the uranium market. Even amid uranium supply shortfalls, we perceive there is a growing prospect for a nuclear renaissance.

We remain invested in the sector, while at the same time cognisant of the risks.

Thank you for reading.

Andrew Limond, Varun Dutt

The Sprott Physical Uranium Trust has purchased less than 3mn lb to end-September 2023, vs ~18mn lb in 2022.

For our original uranium investment thesis, see the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q1 2019 (pp.4-12) and the following Seraya Insight: ‘Anticipating the End of the Downcycle in a Radioactive Sector’. For other more recent updates concerning our view on the uranium market, see the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q1 2021 and Q2 2022, as well as the following Seraya Insights: ‘Uranium: Reflexivity in Action’ and ‘Uranium: the Utility Contracting Cycle Finally Commences’.

Thanks to Alex M of Eightstone for his regular uranium news updates.

For more details, see the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q2 2022 and the following Seraya Insight: ‘Uranium: the Utility Contracting Cycle Finally Commences’.

The seven member countries of IBNI are: Canada, France, Japan, South Korea, the UAE, the UK and the US.

While overall WNA demand projections are similar, the demand breakdown has changed. Construction delays in countries such as China and India are offset by US reactor life extensions, France’s new-build reactor plans and a reversal of South Korea’s nuclear phase-out.

There have been bills introduced in the House and the Senate which seek to ban Russian uranium.

One proposal (which passed a US House subcommittee earlier this year) would gradually restrict access to Russian uranium for US utilities on a ‘slide down’ basis by allowing waivers for several years. However, these waivers would be fully phased out by 2028, not permitting any Russian imports from that year.