Uranium: the Utility Contracting Cycle Finally Commences

More twists and turns for uranium – the bull market strengthens as the utility contracting cycle finally takes off

This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

This Insight is an extract adapted from the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q2 2022.1

Our last detailed update on the uranium market was in April 2021.2 In this letter, we reminded investors of the original bullish investment case for uranium which we had first laid out two years earlier.3

We saw a steady outlook for uranium demand (driven by China in particular, as well as ‘decarbonisation’ demand), along with a serious supply deficit and falling inventories. We anticipated that this meant that the price of uranium would have to more than double (from the US <$30/lb level where it stood in early-2021) towards the marginal cost of production for the yellow metal (which at the time we estimated to be close to US $60/lb). This would be in order to incentivise sufficient production to meet reactor demand.

Our investment thesis was that nuclear utilities around the world would need to pay substantially higher prices to secure long-term offtake agreements with the few beleaguered uranium miners which had managed to survive the brutal decade-long downcycle. We expected that this development would catalyse an upward movement in the share prices of the uranium miners, developers and explorers. We thus began to invest in the equity of various uranium companies.

While the price of uranium and the stock prices of the miners have moved higher since we first invested in the sector, our investment thesis has not played out exactly as expected.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Unexpected Developments

Back in early 2021, we noted that the stock prices of uranium companies had started to rally hard (+80-400% from November 2020 to April 2021) despite a much more modest move in the uranium spot price. This was as optimism around nuclear power increased. By that stage, however, there had been little news regarding increased contracting activity from the utilities.

As we entered the autumn of 2021, another catalyst emerged which drove the spot price of uranium substantially higher. This came in the form of a uranium holding company which had been restructured into a trust by its new manager. This uranium holding company proceeded steadily to buy up large amounts of uranium in the spot market.

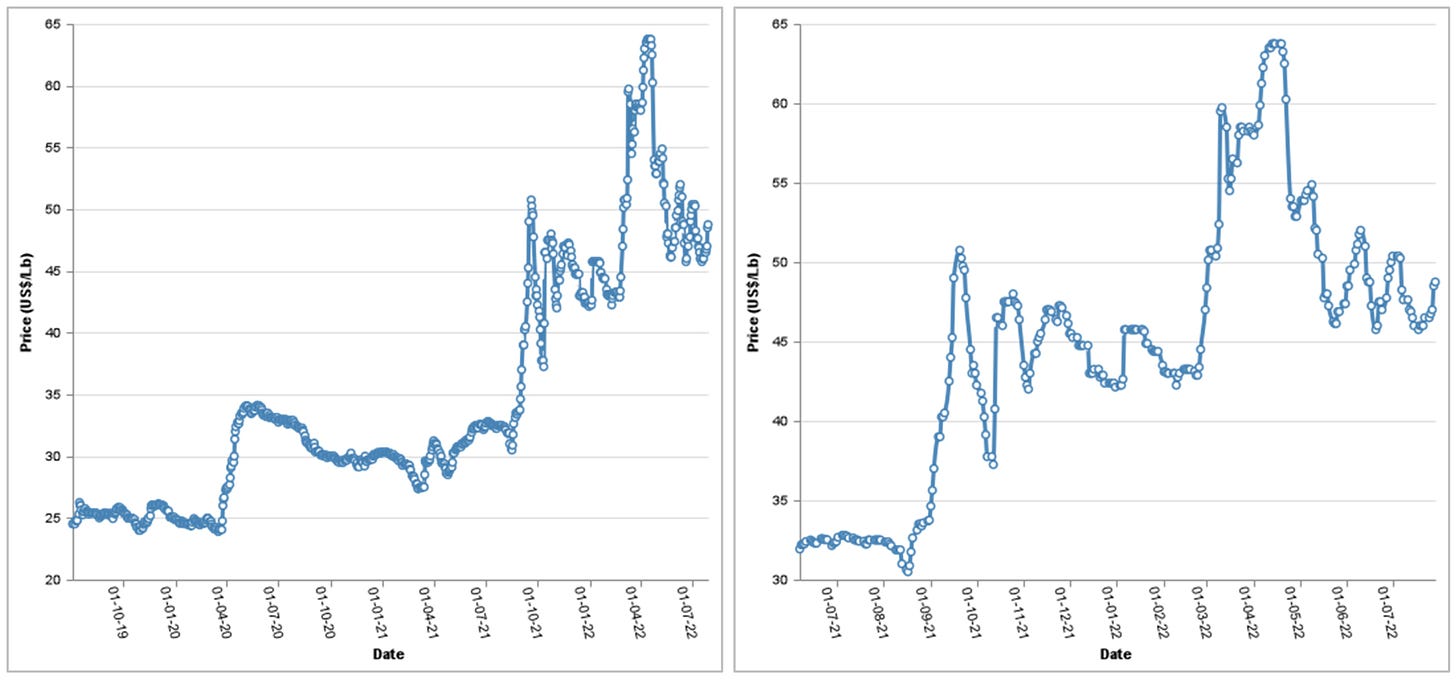

The actions of this trust pushed up uranium spot prices from US ~$32/lb at end-July 2021 to a high of US ~$64/lb in April 2022 (Figures 2.1-2.2). In turn, this also catalysed a rally in the stock prices of uranium miners and juniors in Q1 2021.

Since the restructuring, the trust has grown its holdings of yellowcake from 18.1mn lb to 57.1mn lb, a more than threefold increase. The trust’s uranium holdings are now equivalent to one-third of total annual demand for the metal, and are valued at slightly less than US $3bn.

This uranium has effectively been sequestered on the trust’s balance sheet4 in an apparent attempt to ‘accelerate price discovery’. In other words, the trust appears to have launched an attempt to corner the spot market.5

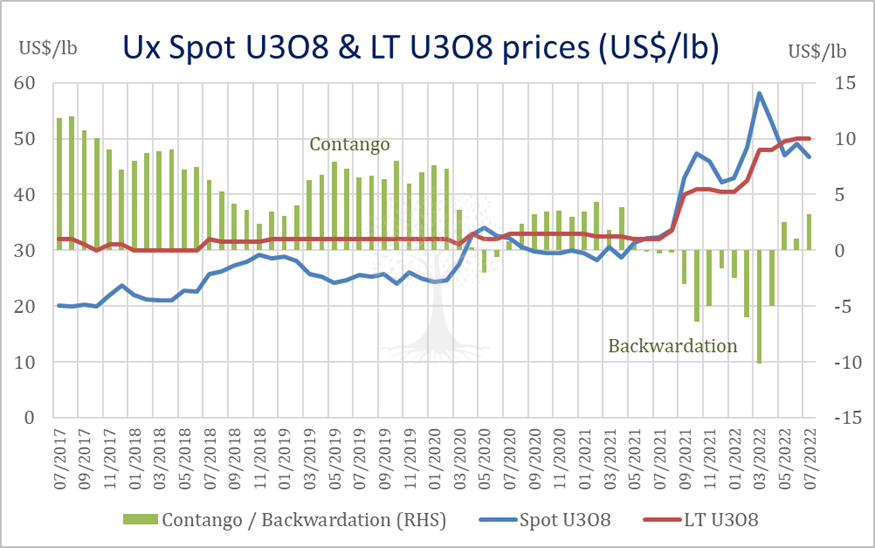

The rise in the long-term price of uranium, however, lagged behind the rapid acceleration in the spot price. This led to backwardation – an unusual state of affairs in the uranium market (which has historically more often been in contango). At the peak of this backwardated market in March 2022, the end-month spot price stood at US $58.2/lb and the long-term price at US $48.0/lb, a backwardation of more than US $10/lb (Figure 3).

Even as both the spot price and forward price of uranium have risen in 2022, however, the stock prices of uranium equities have fallen. ‘Benchmark’ uranium sector ETFs, the Global X Uranium and the Sprott Uranium Miners ETFs, fell by -18.0% and -20.7% during H1 2022, even as the U3O8 spot price rose by +23.5% over the same period.

The weakness in the stock prices of uranium miners and juniors coincided with a general equity market sell-off in H1 2022 as global liquidity conditions tightened. This appears to have been further exacerbated by a correction in energy and mining stocks from May.6

There also appears to have been heavy retail investor interest in the uranium stocks, and possibly also an overlap between cryptocurrency and uranium stock investors (as championed and hyped by ‘thought leaders’ on Twitter, as well as investment ‘research platforms’ such as Realvision). We surmise that as cryptocurrencies collapsed in H1 2022, retail investors might have also sold down their uranium stocks, possibly to meet margin calls.

The Utility Contracting Cycle Commences

Most importantly, quietly and in the background, a utility contracting cycle has finally commenced.

Industry consultant UxC recently reported that in H1 2022, nuclear utilities contracted for ~72mn lb of uranium. This is already more than the amount contracted for the whole of 2021 and is an extremely bullish signal for the sector. The long-term contract price of U3O8 has started to creep up even as the spot price has pulled back, and so the market has moved back into a ‘healthier’ state of contango (Figure 3).

Several flagship uranium mine restarts have been announced, including Paladin’s Langer Heinrich mine in Namibia and Boss Energy’s Honeymoon mine in Australia. The management of both projects had been resolute that they would only restart these mines if it were possible to secure an attractive return for shareholders. These conditions now appear to be in place.

Some investors, however, are concerned that the bulk of long-term utility contracts were signed in Q1 2022, with only a small amount in Q2 (for example, Cameco signed term contracts to supply 40mn lb of U3O8 in Q1, but only 5mn lb in Q2).7 We are less worried, and believe the Q2 ‘contracting slowdown’ happened for two main reasons:

In the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, western nuclear utilities have primarily been focused on replacing conversion and enrichment contracts with non-Russian suppliers, rather than sourcing and contracting new supplies of U3O8.

Uranium miners are in no particular hurry to sign term contracts given their expectation that prices will move higher, towards the marginal cost of production, in the short- to medium-term.

The expectation of higher prices is being driven by tight supply-demand dynamics, but also by rising costs. Given inflation in the mining sector, we estimate that the global marginal cost of production for uranium has now risen to US >$70/lb.

It is thus unsurprising that miners are hesitating to commit large amounts of future production at current prices. Although it might make sense for juniors to sign enough contracts to restart mines and get back into production, it is also rational for them to hold off on committing full production capacity at this stage. Instead, they would like to wait to ‘layer in’ contracts at higher prices and on better terms.

On the demand side, it has been positive to note several nuclear reactor construction starts in China during H1 2022. Moreover, on 7 July, the European Union chose to label nuclear (along with gas) as a transitional ‘green fuel’, which could potentially unleash a large amount of badly needed investment in the sector.

Uranium as a Call Option on Geopolitics

The big potential bull story for uranium, however, is now being driven by geopolitical factors.

On the back of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, there is a growing shortfall of gas in Europe. European nations are acutely aware of their energy vulnerability, but also remain committed to decarbonisation and the ‘energy transition’. As a result, more nations are committing to expanding nuclear power generation within their borders (although Germany remains a curious and troubled exception).

As noted in previous letters, there is also a geographical imbalance between the places where uranium is produced and consumed. The bulk of uranium production (i.e., mining, conversion and enrichment) is carried out in Asia and Russia, while the majority of uranium is consumed in the nuclear reactors of western nations.8

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the resulting sanctions on Russia from most of the western world,9 there now seems to be a reasonable chance that the uranium market will return to a state of ‘bifurcation’ (which existed prior to the 2000s). In other words, western nuclear utilities will likely look to source yellowcake, conversion, enrichment and fuel fabrication services from ‘friendly nations’, while Russian and Chinese client states will look to source these services internally and from their allies.

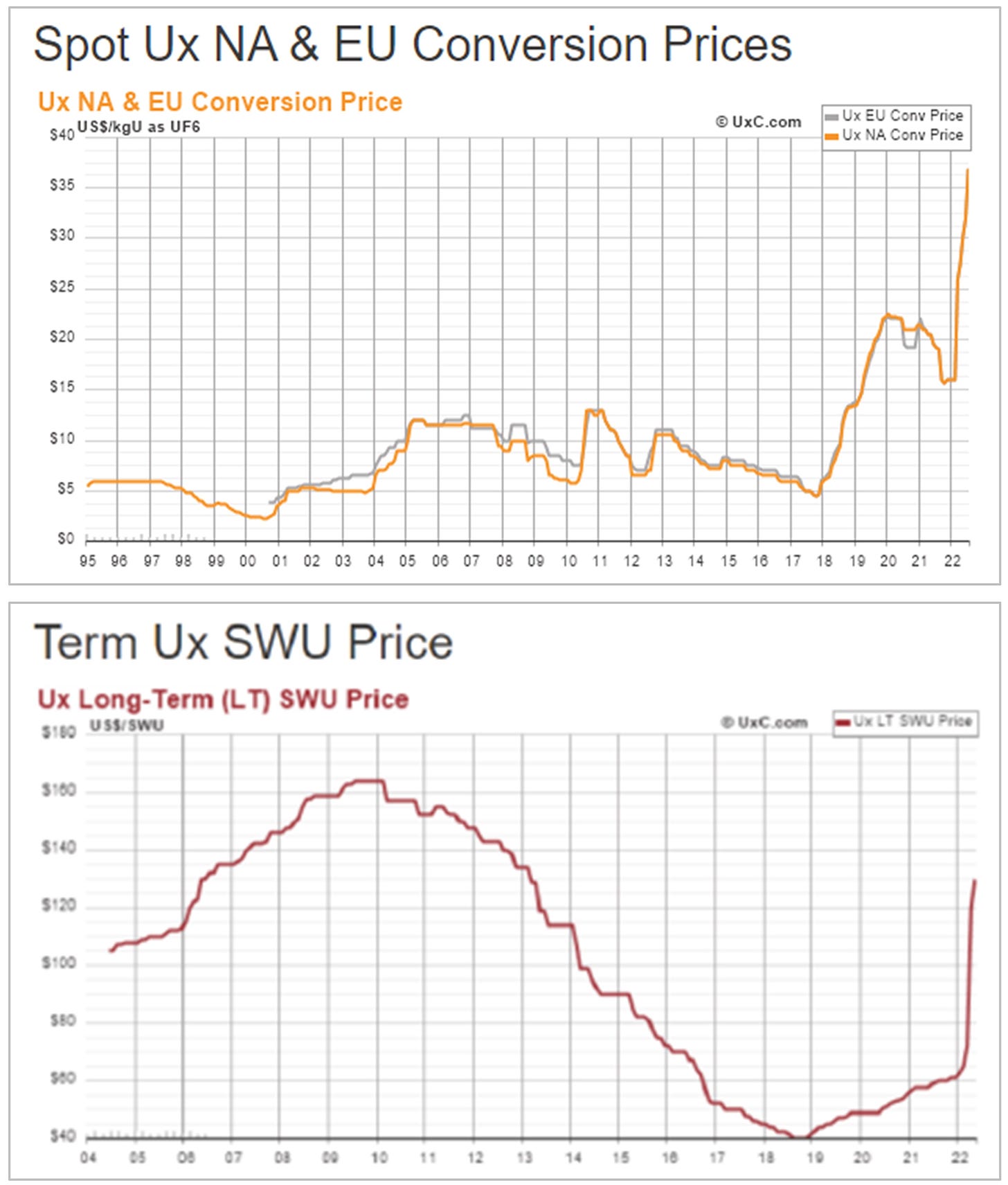

Although the West has not yet introduced formal sanctions on the Russian nuclear services behemoth Rosatom, there are already US senators agitating for this to happen. Even without formal sanctions being introduced, however, it is noteworthy that western nuclear utilities are already rushing to sign source conversion and enrichment contracts with friendly nations. Indeed, it is this which explains the rapid rise in the price of these services since the Russian invasion of Ukraine (Figures 4.1-4.2).10

Why would the bifurcation of the uranium market be such a big deal? The marginal cost of mining uranium in the west (together with friendly nations) is substantially higher than the current global marginal cost of production (currently underpinned by cheap Kazakh supply).

Major Canadian uranium miner Cameco recently estimated that if bifurcated markets were to become a reality, the marginal cost of production for uranium would rise to US ~$90/lb.11 We think that this estimate is likely to prove conservative.

There is now also a very real concern as to how sufficient volumes of Kazakh uranium will be able to find its way to market. Until the invasion of Ukraine, uranium travelled through Russia and was shipped to international customers from St. Petersburg. This route is still operating, but there is a serious risk of disruption. Kazatomprom is thus in the process of reinforcing an alternative non-Russian ‘Trans-Caspian’ route to market.12

Volumes for this route are currently limited to ~7mn lb, however, and it does not yet appear to be open to certain western miners which partner with the company on some of their Kazakh projects. Indeed, Cameco recently indicated that it has chosen to suspend deliveries of the attributable Kazakh production from its Inkai JV for the time being (although for now it can probably access some uranium through swaps on Kazatomprom inventories held abroad).

In 2021, Kazakhstan was responsible for ~45% of the global production of U3O8. So, if for any reason it became difficult or impossible to deliver Kazakh uranium to the international market (e.g., because of further unrest in the country, potential developments in Russia or shipping insurance restrictions), then this would have the potential to cause a massive price shock.

In summary, the recent sharp correction in the stock prices of uranium miners and juniors thus belies increasingly supportive supply-side dynamics. There is also further potential for non-linear geopolitical shocks to catalyse a sudden price spike in uranium.

Indeed, we believe that the current disconnect between fundamentals and stock prices likely provides the best buying opportunity for uranium stocks since we first became involved in this sector in 2018. Given the risks of market bifurcation, we think it makes sense to focus on western producers and uranium holding vehicles.

Major risks to this investment thesis still exist. This includes a nuclear accident (similar to the Fukushima disaster in 2011, or perhaps involving military damage to a reactor in Ukraine), Another risk to uranium prices might be a sudden end to the war in Ukraine and the emergence of détente between the US and Russia (which we currently judge to be unlikely). In the near-term, investors should also be concerned about liquidity flows in and out of this highly volatile sector.

Thank you for reading.

Andrew Limond

The original source material has been edited for spelling, punctuation, grammar and clarity. Photographs, illustrations, diagrams and references have been updated to ensure relevance. Copies of the original quarterly letter source material are available to investors on request.

See the Panah letter to investors for Q1 2021 and the following Seraya Insight: ‘Uranium: Reflexivity in Action’.

For our original investment thesis on uranium, see the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q1 2019 (pp.4-12) and the following Seraya Insight: ‘Anticipating the End of the Downcycle in a Radioactive Sector’.

The uranium trust is able to act in this way – effectively ‘locking away’ uranium inventories – as it is able to issue more shares to buy uranium whenever the shares trade at even a slight premium to NAV. On the other hand, the trust has restrictions which prevent it from selling uranium to buy back shares when the stock price trades at a discount to NAV. In contrast, the previous manager of this uranium holding company was able to dispose of uranium to buy back shares when shares traded at a discount to NAV.

The spot price of uranium is an imperfect benchmark, as historically it reflected a price at which a handful of less price-sensitive producers disposed of a small volume of non-contracted yellowcake. The vast majority of uranium is bought by the utilities via longer-term contracts with the miners, at prices and on conditions which are opaque. Historically, term contracts were (almost) always at a premium to the spot price, although this changed in 2021.

This is despite the fact that uranium is much less economically sensitive than other commodities given steady baseload demand from nuclear reactors and a long-term contracting cycle.

See the transcript of the Cameco Q2 2022 results call for details.

See the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q1 2019 (p.10) and the following Seraya Insight: ‘Anticipating the End of the Downcycle in a Radioactive Sector’.

For more commentary on the Russian invasion of Ukraine, see the Panah letter to investors for Q1 2022 and the following Seraya Insight: ‘Reflections on the Russo-Ukrainian War and a “New World Order”’.

Note that Russia currently accounts for ~30% of global uranium conversion capacity, and ~46% of the global enrichment market.

As described in the recent Cameco Q2 2022 results call.