Reflections on the Russo-Ukrainian War and a ‘New World Order’

The Russian invasion of Ukraine, the effect of the war on energy and commodities, back-to-the-future for geopolitics, the 'new world order' and the challenge to US Dollar hegemony

This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

This Insight is an extract adapted from the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q1 2022.1

Less than a quarter of the way into a new decade, the four horsemen of the apocalypse are riding high. Pestilence, war and death are already being visited upon the world, with famine soon set to strike.

In early 2020, we wrote that history would likely see the coronavirus crisis as a symbolic turning point of a similar magnitude to the Fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.2 We noted that the global reaction to the pandemic had already rapidly catalysed a massive shift in the Zeitgeist, heralding a transformation in the political, social, economic and technological affairs of mankind.

Two years later, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has laid bare the new geopolitical realities of the 2020s. The catastrophic scenes unfolding in the country are exacting a tragically high human cost. US-Russian relations are at their lowest ebb in decades, and the risk of nuclear war is probably at the highest level since the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. In the coming years, the Russo-Ukrainian War is likely to have significant lasting effects on the existing world order.

In this letter, we examine these events from a macro and an Asian perspective, attempting to draw out some of the more long-term geopolitical and investment implications of the conflict.

In Q1 2022, the world has arguably just experienced one of the most significant geopolitical events for a generation.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The Power of Eurasia, the ‘Geographical Pivot of History’ and the ‘Foundations of Geopolitics’

‘Non-Aligned’ Nations and the End of Western ‘Fiat Currency Neutrality’

Personal Reflections

In autumn of the year 2000, after studying Chinese abroad for several months as part of my degree course, I took the scenic route home – travelling by rail through China, Mongolia and Russia. I was accompanied on this trip by my 80-year-old grandfather, who journeyed with me from Beijing to St Petersburg as we traversed Russia on the Trans-Siberian railway.

I knew little about Russia when I started the trip, but I enjoyed learning more as I travelled – from books, from the people we met along the way, and from my grandfather. On our journey, we stayed with several families who were extremely hospitable. They shared their homes with us for a few days and also told us about their lives.

Almost a decade after the fall of communism, life was still tough for most people in the former Soviet Union. Our tourist dollars were highly sought after. As a student from the West, I was also surprised to learn that so many of the people we spoke to, especially among the older generation, yearned for the greater economic certainty of the Communist era.

The 1990s had been a difficult decade for most Russians (other than perhaps a few oligarchs who took advantage of the chaotic company privatisations of the early 90s). In 1998, the Russian financial crisis and chronic food shortages played an important role in Boris Yeltsin’s decision to step aside as President the following year.

President Yeltsin’s preferred successor was Vladimir Putin, a little-known politician from St Petersburg who had recently been elevated to the head of the FSB (successor to the KGB) – an emerging ‘law and order’ leader who seemed to share a nostalgia for Soviet times.

Vladimir Putin was inaugurated for his first presidential term in May 2000, just a few months before we started our trip. Floating past the autumnal birch forests of the Siberian taiga and marvelling at the wonders of St Peterburg’s Winter Palace, I had little inkling of the importance of the political changes underway in the country at the time.

It was to be more than 15 years before I travelled Russia again, this time to visit my brother who moved to the country in 2014 to work in the oil and gas industry. Over the next few years, I was fortunate to be able to meet with him in several places around Russia and in neighbouring countries – from Moscow to Samara to Vladivostok, and Almaty to Tblisi – and learn a little more about these places, in no small part thanks to my brother’s excellent Russian.

Russia had changed almost beyond recognition since my first trip to the country – each place we visited brimmed with a much greater level of affluence and confidence than before. Russia had clearly come a long way in fifteen years. This was despite the economy suffering from a recent crash in the oil price, and from the international sanctions implemented in the wake of Russia’s annexation of Crimea in early 2014.

In hindsight, these sanctions seem to have been better at creating hardships for the Russian people rather than changing the minds of the country’s leaders about their right to control Crimea. The sanctions also had some other strange effects…

Thanks to sanctions and countersanctions, it became much harder to buy Norwegian smoked salmon in Russia. It was not long, however, before the Faroe Islands (part of Denmark although not in the EU) stepped into the breach, sidestepping sanctions to export their salmon to Russia instead. Friends in Vietnam also wryly noted that Norwegian salmon imports had gone through the roof – were some of the fish perhaps migrating back towards the Arctic? In any case, any Russian knew that the best smoked salmon was their own, from Kamchatka.

President Putin’s decision in 2015 to ban all food imports from ‘unfriendly countries’ initially caused food inflation to spike. The public destruction of foreign produce also caused a stir.

Thereafter, the variety and volume of Russian domestic agricultural produce increased dramatically. World-class farm-to-table dining restaurants sprung up in Moscow, better befitting Russia’s status as an agricultural superpower. Sanctions rarely work as intended.

Panah became more interested in potential Russian investment opportunities from 2020, as our concerns grew over the state of the world’s energy markets.3 When it comes to energy, Russia is simply too big to ignore.

There were also several other factors working in Russia’s favour. One was valuation – Russian companies (especially resource companies) were among the cheapest in the world, sporting low single-digit earnings multiples and fat double-digit dividend yields. Another factor was governance – investors had been encouraged at the steady pace of corporate governance improvements among the country’s companies over the last decade.

It thus seemed reasonable at the time to invest in some Russian energy holdings as part of a broader energy portfolio. After all, Russian companies have been responsible for providing a large proportion of the low-cost energy which allows Europeans to enjoy their high standard of living. Russian energy is also increasingly important for China.

Even though geopolitical tensions between Russia and the West had been rising, it seemed logical to assume that the longstanding mutually-beneficial trade arrangement – Euros and Dollars for Russian resources – would persist as it had since the 1980s. What could go wrong?

The Invasion

Even as the US government warned in late 2021 of the potential for an imminent invasion of Ukraine by Russia, we believed this to be unlikely. Such an action would likely come at an extremely high cost for both sides, we thought, and in the long-term would likely prove to be self-defeating for Russia.

Moreover, the US had a questionable track record when it came to declassifying intelligence to justify foreign policy action. This suggested that some degree of scepticism regarding warnings of imminent invasion might be warranted.

On this occasion, however, our scepticism was ill-founded and US intelligence was proven correct as Russia launched an invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022.

The investors and institutions closest to Russia seemed to be most surprised when the invasion happened. One reason for this was that President Putin’s invasion appear to have been shared with very few people in advance. The Russian domestic media also did little to prepare public opinion in Russia for military action, which was surprising.

Many observers (including ourselves) placed too much weight on ‘rational economic analysis’ which argued against invasion, rather than fully comprehending the Tsarist historical calculus and ruthlessness which President Putin himself seems to have embraced.

As the war enters its third month, the ‘fog of war’ hangs heavy over the battlefield, and reliable information is hard to come by.

One thing that does seem clear, however, is that the human cost of the war on both sides has been horrific. While accurate casualty numbers are disputed, reports indicate that an extremely large number of Russian soldiers, as well as Ukrainian soldiers and a tragically high number of civilians, have so far been killed or wounded. The war has also caused the largest refugee crisis in Europe since WWII, with an estimated ~25% of the ~40mn population of Ukraine displaced from their homes.

The Western media has been quick to publish triumphant reports that President Putin had miscalculated in thinking that it would be easy to achieve his military aims quickly. While effective fighting from Ukrainian soldiers equipped with Western weapons and ordnance does appear to have pushed back Russian soldiers from Kyiv, this also means that the war has transitioned towards a new phase – an even more brutal and grinding conflict in the south and east of Ukraine, as exemplified by the siege of Mariupol.

Western nations reacted to the Russian invasion of Ukraine remarkably swiftly, implementing a broad swathe of sanctions on Russian individuals, companies and institutions (including the central bank). Indeed, the Russian invasion has served to unify a fractious EU, promote trans-Atlantic cooperation, catalyse a historic change in German defence policy away from pacifism, and even boost NATO membership (with Sweden and Finland seemingly set to join the alliance soon). President Putin did not seem to have anticipated this outcome.

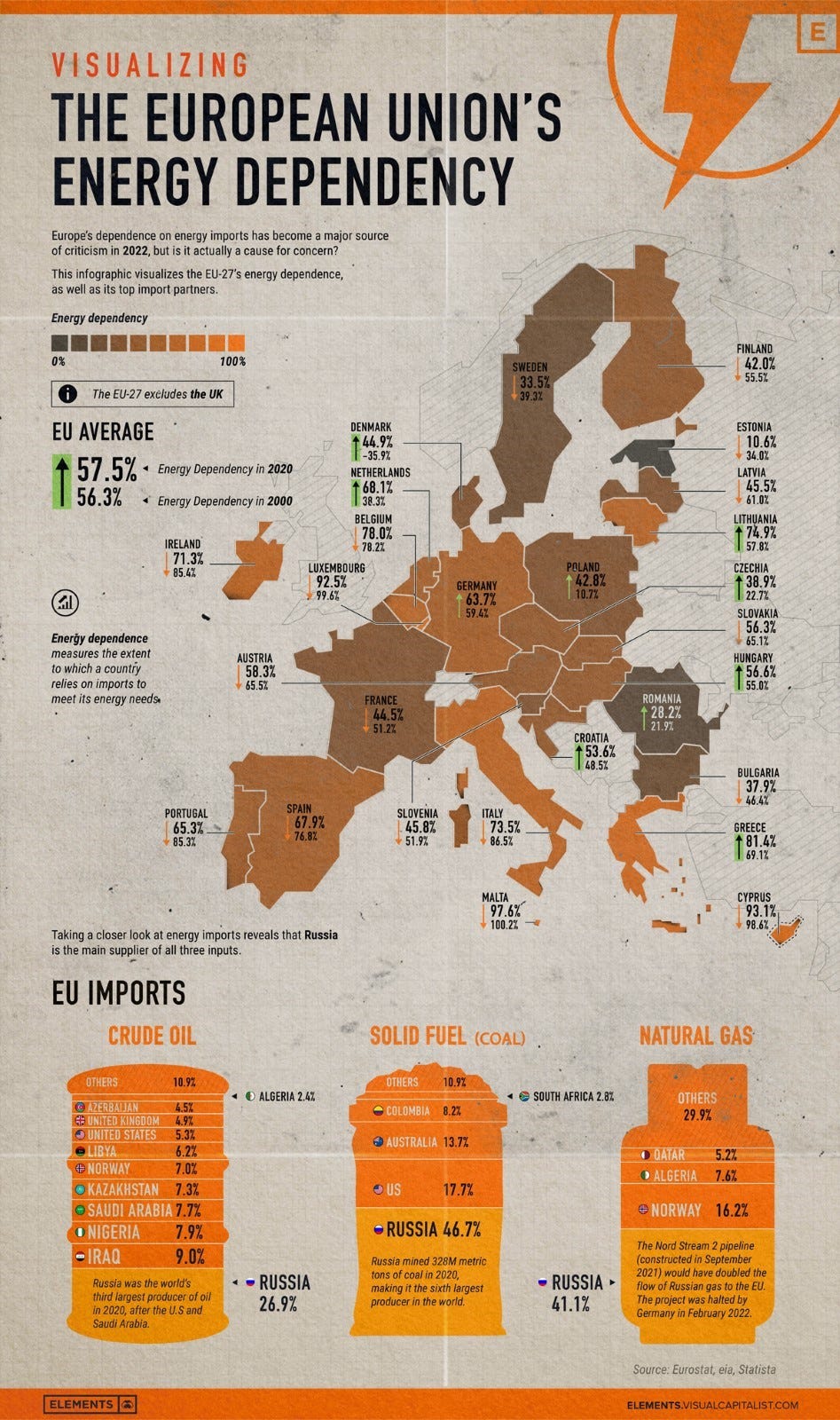

Europe has made it clear that it wishes to reduce its dependence on Russian hydrocarbons to zero as soon as possible. While it has been possible for the EU to implement a ban on Russian coal already, the EU will likely only be able to follow the UK and US with a ban on oil by year-end at the earliest (although given the economic damage this would cause in Europe, vetoes from some EU members are possible).

The EU is also seeking to impede Russia’s ability to export oil and oil products around the world by placing a European insurance ban on ships carrying Russian oil.

Reducing gas imports from Russia is a larger challenge given that >40% of the EU’s gas comes from Russia (Figure 5).4 The EU’s current ambitious plan is to reduce demand for Russian gas by two-thirds by end-2022, although it would likely take many more years to phase out Russian gas completely (assuming Russia does not ban gas exports to the EU first).

Europe currently has significant LNG bottlenecks and capacity constraints. Even as new gas projects come online, it will likely take years to build out new US liquefaction and EU regasification capacity.

Global gas prices thus seem set to remain at elevated levels for many years yet to come – the price to pay for years of naïve European energy policy. With European gas prices trading at multiples of pre-Covid levels, vast swathes of European industry are at risk of becoming uncompetitive.

The Kremlin’s strategic effort to sow discord among Western nations is likely only in its early stages. Given Europe’s resource vulnerabilities, Russia’s current focus is on ‘weaponising’ hydrocarbon supply by restricting access to “unfriendly countries”. Even in the Cold War, the gas kept flowing to Europe. Now, however, Russia seems willing to take advantage of Europe’s high dependence on Russian gas to exert leverage and extract concessions.

Gazprom (Russia’s gas export powerhouse) recently announced it would cut off gas supply to Poland and Bulgaria as the gas purchasers in these countries have not complied with the Kremlin’s demands to cooperate with its new Ruble-based payment mechanism. Several other European gas importers, however, have reportedly already opened accounts with Gazprombank as requested. A handful have reportedly already made payment in line with Russian demands, despite the EU’s insistence that this would violate sanctions against Moscow.

Other gas-importing European countries will have to decide in the coming weeks and months whether to comply with Russian payment terms. This creates the potential for more tensions between EU countries.

Gas is not the only commodity where Russia can bring leverage to bear. Fertiliser export restrictions are already in place and have recently been extended. Given gas is the main feedstock for nitrogen-based fertilisers, higher gas prices in Europe have also meant surging nitrate prices, further raising the risk of global food shortages.

President Putin likely believes that Europe is poorly placed to withstand the economic damage that higher resource prices will bring, and that as the continent wallows in a stagflationary mire, public opposition to Russian imperial aspirations in Ukraine will wane. The European outlook does look increasingly challenging – unemployment in H2 2022 seems likely to rise just as many people struggle to heat their homes this winter. The result will likely be greater political polarisation and unrest.

If such Russian strategies do not work, however, and President Putin fails to achieve his war aims in Ukraine on a timely basis, this then also raises the risk of escalation on other fronts. Cyberattacks by Russia could increase dramatically (having so far been relatively limited in scope). There might be further sabotage of vital global infrastructure (such as subsea internet cables, as in Svalbard earlier this year). The probability of the conflict spreading to Moldova and beyond also appears to be rising. As Russian shortages of conventional weapons and parts increase, attacks with chemical or tactical nuclear weapons also seem possible.

With peace talks at an impasse and Russia seemingly experiencing military setbacks, the Western strategy in Ukraine appears to be evolving towards an attempt to prolong the war and provide more weapons in an attempt to “weaken Russia”. The UK is now also on the record as stating that Ukrainian attacks on Russian soil (even with weapons provided by the UK) are legitimate.

Russia also increasingly seems to be preparing for a long war in Ukraine, and has made it clear that it sees rising Western involvement as highly provocative. Patriarch Kirill of the Russian Orthodox church has framed the conflict as a ‘holy war’. The links between the Russian Orthodox church and the Russian military nuclear command are reported to be strong. Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov recently has warned that the Ukraine conflict is descending into a proxy war between NATO and Russia, with a non-trivial risk of nuclear war.

All sides would be well-advised to seek an off-ramp, although at present there is no sign of détente.

The Power of Eurasia, the ‘Geographical Pivot of History’ and the ‘Foundations of Geopolitics’

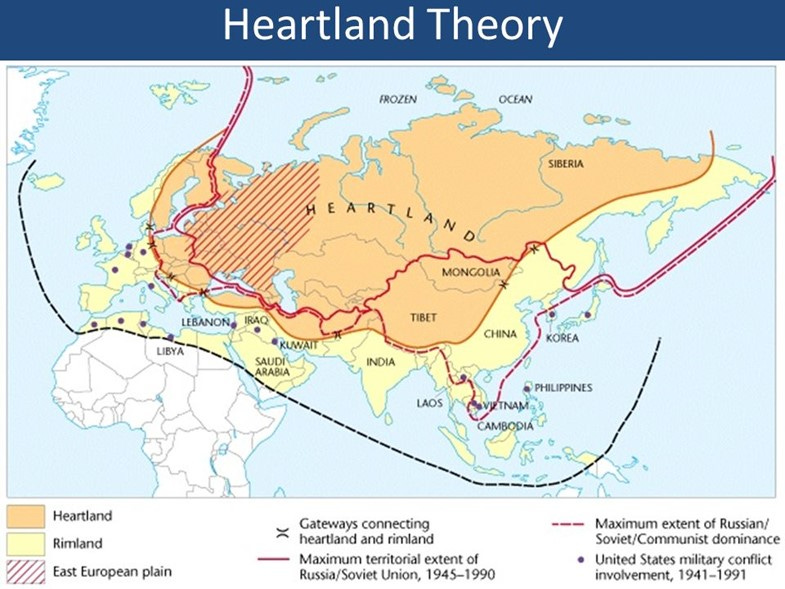

In 1904, Sir Halford John Mackinder published ‘The Geographical Pivot of History’, an article promoting his new brand of global geopolitical analysis. This later become known as ‘Heartland Theory’:

“Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland; who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island; who rules the World-Island commands the world.”5

In Mackinder’s thinking, the East European plain extends from eastern Poland in the west to the Urals in the east, while the Heartland stretches from the Volga in the west to the Yangtze in the east, and from the Arctic in the north to the Himalayas in the south (i.e., most of Russia and northern China). The larger World-Island encompasses the entirety of Eurasia, which boasts around of half the world’s resources.

While this geopolitical theory might now seem slightly outdated given the importance of sea and airpower in modern warfare, similar thinking to Heartland Theory has exerted an important influence at various times in history (e.g., the Crimean War and possibly the Nazi invasion of Russia). In 1971, Henry Kissinger’s secret visit to China served to reinforce the growing schism between Russia and China, thereby pre-emptively ‘dividing’ these two powerful potential Eurasian allies.

In his 1994 book ‘Diplomacy’, Kissinger echoed earlier warnings by Prof Nicholas J. Spykman:

“Russia, regardless of who governs it, sits astride the territory which Halford Mackinder called the geopolitical heartland, and it is the heir to one of the most potent imperial traditions…”

“Geopolitically, America is an island off the shores of the large landmass of Eurasia, whose resources and population far exceed those of the United States. The domination by a single power of either of Eurasia's two principal spheres – Europe and Asia – remains a good definition of strategic danger for America, Cold War or no Cold War.

“For such a grouping would have the capacity to outstrip America economically and, in the end, militarily. That danger would have to be resisted even if the dominant power was apparently benevolent, for if its intentions ever changed, America would find itself with a grossly diminished capacity for effective resistance and a growing inability to shape events.”6

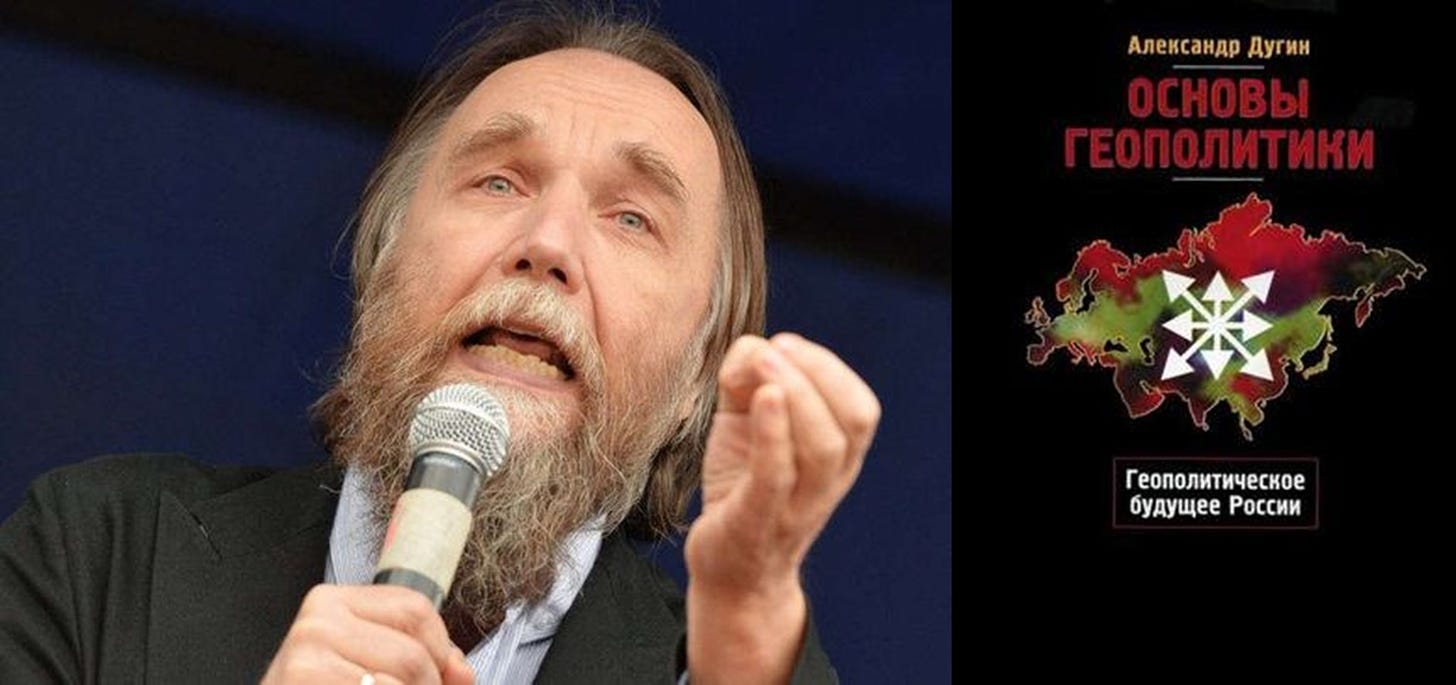

Russian geopolitical theorist Alexander Dugin, author of ‘Last War of the World Island’, is the Rasputin-like figure who appears to be the architect of President Putin’s strategy to rebuild Russian power, dominate Eurasia and create a more multipolar world.

In his 1997 treatise, ‘The Foundations of Geopolitics’ (Figure 7), Dugin “advocates a fairly sophisticated program of subversion, destabilisation, and disinformation spearheaded by the Russian special services, supported by a tough, hard-headed use of Russia's gas, oil, and natural resource riches to pressure and bully other countries into bending to Russia's will.”7

According to Dugin, Russia’s first step should be to control Ukraine: "…without resolving the Ukrainian problem, it is, in general, senseless to speak about continental politics."8 Only then can Russia hope to dominate Eurasia.

Russia and China – the quintessential Eurasian powers – are now enjoying their closest relationship since the early days of the Cold War. While the interests of these empires do not coincide perfectly, Presidents Putin and Xi appear to have formed a strong personal bond – partially founded on mutually antipathy towards the US and ‘Western values’ – which has drawn the two countries closer together.

On 4 February 2022, China and Russia announced a deepening strategic partnership as Presidents Xi Jinping and Putin met on the eve of the Winter Olympics in Beijing. “Friendship between the two States has no limits, there are no ‘forbidden’ areas of cooperation”, proclaimed their joint communiqué.9

While Russia remains a resources powerhouse, China has in the past twenty years emerged as the predominant global manufacturing dynamo (and also boasts some impressive commodity stockpiles). By forming a partnership between these two countries with strong complementary attributes, their respective leaders believe they can launch a strong global challenge to the status quo.

Seen in this light, has the Western foreign policy establishment made a serious error by allowing the emergence of a new, strong Sino-Soviet ‘alliance’?

There are of course weaknesses and constraints to the relationship. One serious deficiency is the allies’ lack of advanced semiconductor technology. On another note, China is likely to be the senior partner within the alliance, which might eventually cause tension. Russia’s ostracisation by the West will mean that China by default will become Russia’s most important ally and the biggest commodity customer, which will also mean China is the ‘price-maker’. Over time, as in the past, it also seems probable that tensions will emerge in the new Sino-Soviet relationship.10

For now, however, the Eurasian empires are allied against the West. As Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov gushed in a recent meeting with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi: "We, together with you, and with our sympathisers will move towards a new, multipolar, just, democratic world order."

The ‘New World Order’ – a Challenge to US Dollar Hegemony?

Any attempt to create a ‘new world order’ would almost certainly involve a challenge to the reserve status of the US Dollar. For some time, Russia and China have been dissatisfied with the “exorbitant privilege” that the US Dollar enjoys as the international reserve currency. This system has allowed the US to continue funding its ongoing deficits, which in turn pay for the powerful military which project US foreign policy around the globe.

Among the various functions of an international reserve currency, two of the most important are the ability for other nations to hold forex reserves in that currency (i.e., deep and liquid debt markets) and also to freely carry out trade transactions denominated in that currency.

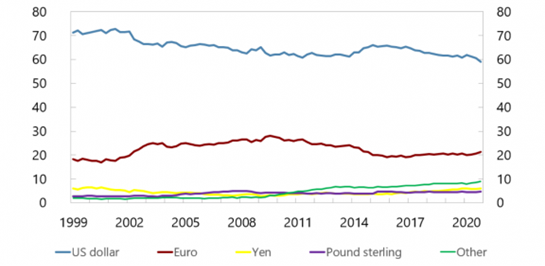

As the US carried out successive Quantitative Easing programs in the wake of the 2008 Great Financial Crisis, Russia and China chose to diversify their forex reserves away from the greenback and towards other currencies and gold.11 China has also sought to invest its national savings in other international infrastructure- and commodity-oriented projects (i.e., the ‘One Belt One Road’ program).12 Both countries have also sought to encourage more trade to be conducted in Rubles and Renminbi, with somewhat limited success to date.13

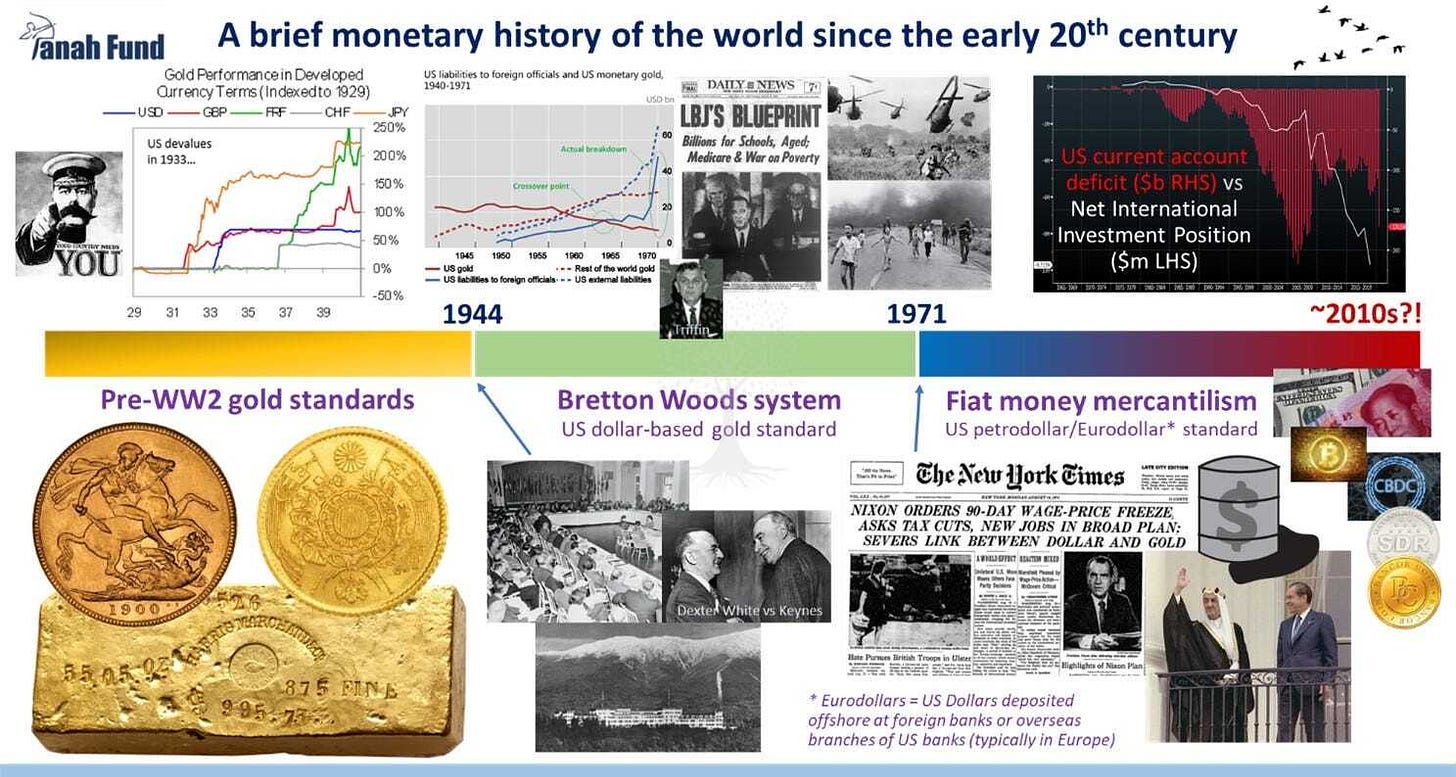

In a December 2020 Panah presentation,14 we recounted a brief monetary history of the world since the early 20th century. This summary outlined the three main monetary systems which have prevailed during this period: the pre-WW2 gold standards; the post-WW2 Bretton Woods system; and the current fiat money mercantilist (US petrodollar/ Eurodollar) regime.

Even if US Dollar hegemony is now facing an external challenge from Eurasia, the bar to challenge the supremacy of the greenback is set extremely high. After all, the only modern example of a change in an international reserve currency was when Sterling slowly ceded its dominance to the US Dollar during the inter-war period, a period of almost three decades which involved two world wars.

While some have advocated that the Renminbi (perhaps in digital form) will soon emerge as an outright competitor to the US Dollar, China has no wish to run a structural current account deficit in the same manner as the US. Moreover, there seems little chance that the CCP would be willing to relinquish any control over the Renminbi, certainly not to the extent that would be required for it to become a major international trade and reserve currency. At present, Chinese domestic political trends are moving in the opposite direction.

So, is it even worth spending time talking about any challenges to the US Dollar’s reserve status? We believe so, as this process will likely indicate the accelerated emergence of a more multipolar world, which we believe to have important investment implications.

A respected market strategist at Credit Suisse, Zoltan Poszar, recently declared the birth of a new monetary system, ‘Bretton Woods III’.15 This thesis embraces his trademark complexity, based on ‘four prices of money’ and their counterparts in the commodity world.

The thrust of Mr Poszar’s proposition is that the Russian invasion of Ukraine has birthed a new commodity-backed monetary regime focused on Eurasia (i.e., Russia and China), which will lead to a massive inflation problem for the G7 (especially Europe).

Where Mr Poszar appears to see a decisive break in the international monetary system, we see an acceleration in the existing trend towards a multipolar world. This time, nobody is sitting down around a table at Bretton Woods to discuss the shape of the international monetary system in an amicable fashion. Instead, real time changes are being forged in adversity.

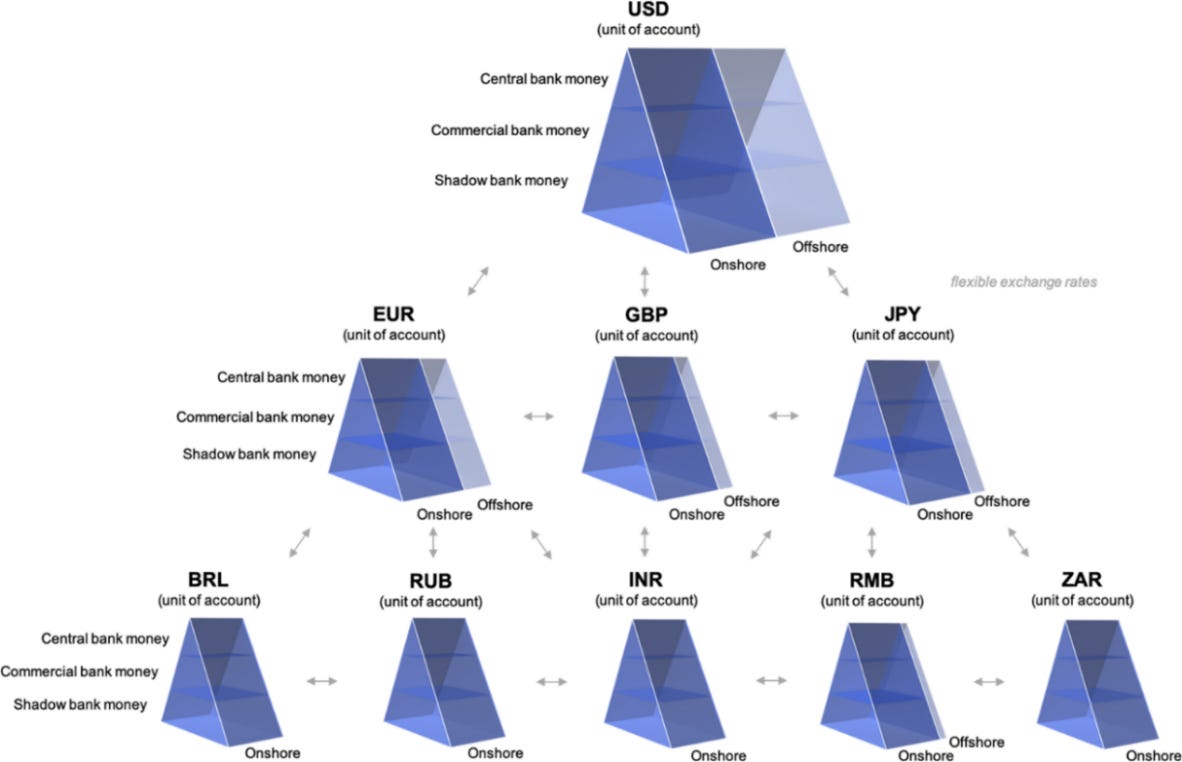

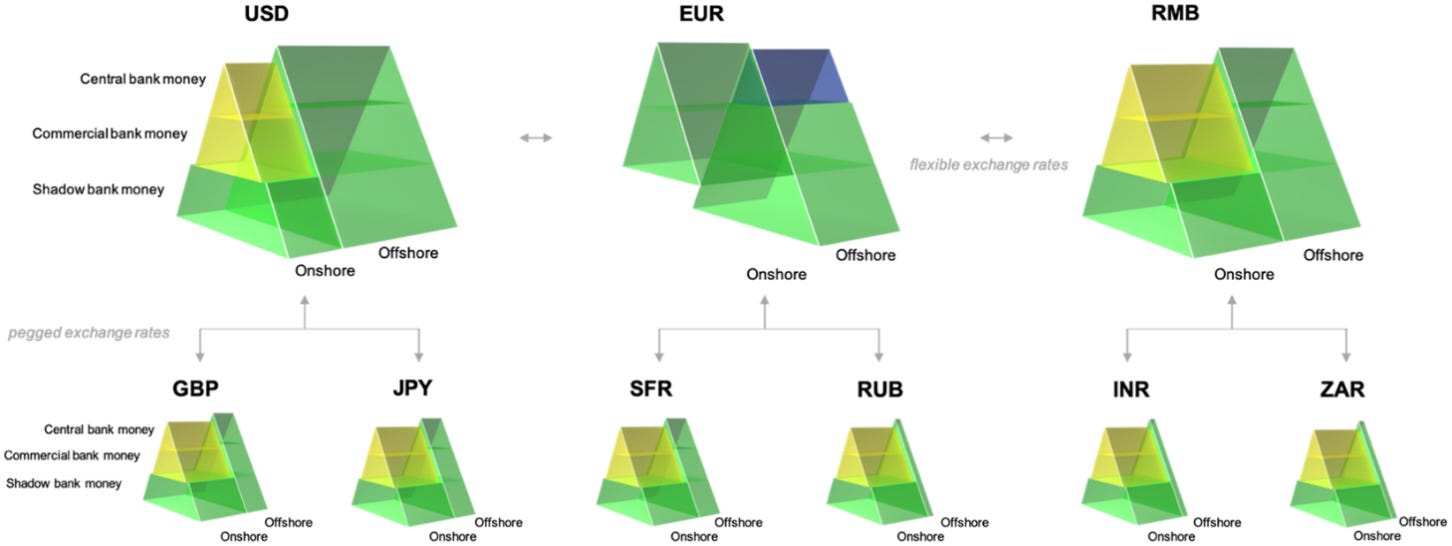

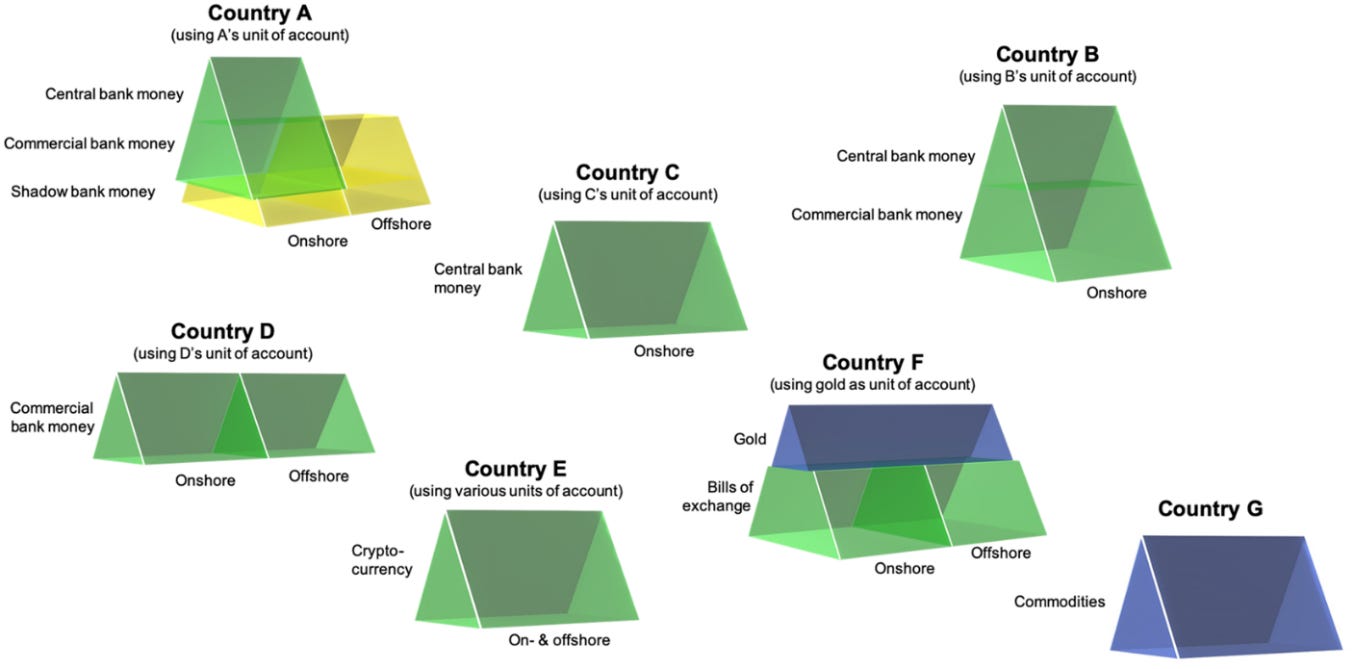

What might a new global monetary system look like? Rather than having a fixed idea about how this new system might evolve, we are trying to keep an open mind. To that end, we find the work of Dr Steffen Murau to be helpful. In mid-2020, he co-authored a paper on the Eurodollar (i.e., ‘offshore dollar’) regime. This examined the past, present (Figure 11.1) and four possible futures of the system.16

One of these four possible futures was an ‘international monetary federation’ (Figure 11.2), which would probably be the optimal monetary system if the goal were to create a more multipolar system with high levels of monetary stability. The design might be similar to the ‘Bancor’ regime proposed by Keynes at Bretton Woods and would probably centre around the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (‘SDR’).

China would likely be supportive of a transition to an SDR-based arrangement – former PBOC governor Zhou Xiaochuan once described the SDR as “the light in the tunnel for the reform of the international monetary system”. Moving in this direction, however, would require high levels of international cooperation, which at present seems unimaginable.

Instead, investors should be wary of the possibility that the global monetary system is already starting to fragment towards a regime which more closely resembles Murau’s ‘competing monetary blocks’ trajectory (Figure 11.3). In a worst-case scenario, there might even be a chance that the global monetary system spirals towards ‘international monetary anarchy’.17

Russia now does appear to be attempting to set up the Ruble as a ‘hard currency’ backed by commodities. Even as Russia slashed its US Treasuries holdings over the last decade, it strongly boosted its holdings of physical gold (Figure 12.1).

Despite confident predictions of sanctions-induced collapse, the official Ruble rate has rebounded to a higher level versus the US Dollar than before the invasion (Figure 12.2). What’s more, this has occurred during a period where the US Dollar has itself been strong against other currencies. Ruble strength is mostly thanks to capital controls and interest rate hikes, as well as continued oil and gas exports.

Not only has Russia started to demand payment for its hydrocarbon exports in Rubles from “unfriendly countries”, it is also threatening to do so for other commodities such as grain, oil and metals. On 25 March, the Russian central bank also introduced a floor price for gold of 5,000 Rubles per gram in the domestic market.18

This measure helped to free up liquidity for Russian commercial banks adversely impacted by sanctions. The Bank of Russia subsequently suspended its floor price gold buying program from 8 April due to a “significant change in market conditions” (i.e., the Ruble rebound). There now appears to be an ongoing discussion within the Russian leadership as to whether to introduce a Ruble gold standard.

The Kremlin has worked hard since the invasion of Crimea in 2014 to build up a ‘fortress’ balance sheet, slashing Russia’s debts (including those dominated in foreign currencies) and adding to its ‘war chest’ of foreign exchange reserves (although half of these are now frozen). As of end-2020, Russia’s gross debt-to-GDP ratio still came in at below 20%, the lowest among all G20 nations. Despite payment difficulties as a result of frozen funds and payment restrictions, Russia has so far made significant efforts not to default on its debt obligations.

A strong sovereign balance sheet and a potential Ruble-gold link also send a message of stability to those countries which still wish to trade with Russia. As the West continues its attempts to crack down on trade with Russia, it does not seem outlandish to imagine a resurgence of Soviet-style bartering and countertrade with ‘non-aligned’ nations (see below). Commodities produced by Russia are in high demand right now, and it would be harder for the US and the EU to impede barter deals compared to trade carried out in US Dollars and Euros.

China is of course the one other country which would be most closely associated with Russia in this new hypothetical ‘currency block’ backed by both commodities and factories. Beijing is expected to be as supportive as possible to Moscow without directly contravening US sanctions on sending military-use material to the Ukraine conflict.19 Although the pace of Russian commodity purchases by China have been slower than expected (partly because of sanctions and partly because of China’s ‘Zero Covid’ lockdowns), these seem likely to increase over time.

Further practical help might involve the PBOC providing liquidity for the portion of Russia’s forex reserves held in Renminbi and gold, facilitating payments via alternatives to SWIFT, as well as reactivating swap lines to support bilateral trade. Direct Chinese investment in Russian commodity companies also seems likely at some juncture (replacing the Western companies which have been quick to divest their Russian holdings).

Even as Russia demands payment for commodities from enemies in Rubles, China has also been trying to encourage Saudi Arabia to price some of its oil sales to China in Renminbi. Saudi Arabia is now reportedly considering pricing a small amount of oil sales in Chinese Yuan, if only as a reminder to the US of its security commitments (amid poor relations between the two countries over human rights concerns, Saudi’s war in the Yemen and an attempted revival of the Iran nuclear deal).

As yet, this is still just a straw in the wind. In the coming months and years, however, we would not be surprised to see more trade conducted in Renminbi.

‘Non-aligned’ nations and the end of Western ‘Fiat Currency Neutrality’

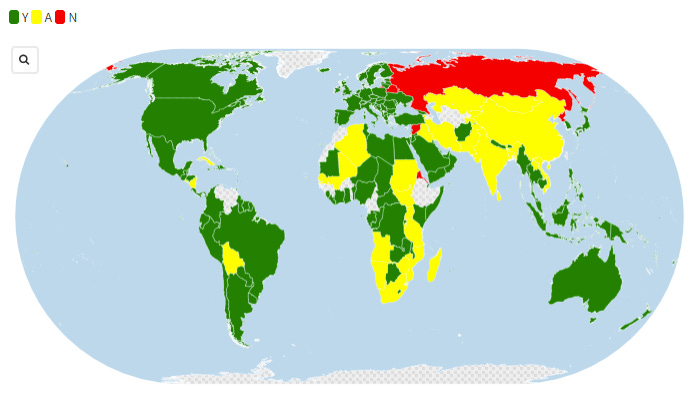

Amid the dominant Western media coverage of the Russian invasion, it is easy to forget that a significant number of countries, representing a majority of the world’s population, abstained from voting for resolutions demanding an end to the invasion of Ukraine during recent votes in the United Nations Security Council (‘UNSC’) and General Assembly (‘UNGA’).

Abstentions in the UNSC included China, India and the UAE. In the UNGA, abstentions included numerous countries (Figure 13), including: Bangladesh, Bolivia, China, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Mongolia, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Tajikistan, Vietnam along with various other African and Central American nations. (Russia and North Korea voted against.)

Many of the abstaining countries might well have seen Ukraine as a distant problem and were more concerned about keeping cordial relations with Russia (in order to maintain access to commodities and other exports).

Public opinion in some countries, particularly the Middle East, also seemed unmoved by pleas that the invasion crossed a line by violating the integrity of a sovereign nation’s borders. For them, that precedent had already been set earlier in the 21st century with the invasion of Iraq in 2003 by the US and its allies.

India’s double abstention (in the UNSC and UNGA) was particularly notable given its supposed geopolitical alignment with the US, Australia and Japan as one of the ‘Quad’ nations.

India supposedly took this decision due to a variety of reasons, including the country’s deep historic relationship with Russia, as well as its dependence on Russian military equipment amid an overriding concern about the military threat posed by China. On a more opportunistic note, since the invasion of Ukraine, energy-poor India has not been shy about attempting to procure more hydrocarbons from Russia at mark-down prices.

Our key takeaway from this is the West will have its work cut out winning over ‘non-aligned’ nations to their cause. For many of these countries, even supposed allies, it makes sense to play the Western and emerging Sino-Soviet blocks off against one another to gain maximum advantage. This will likely involve more ‘hedging’ for non-aligned nations in terms of allocation of trade and forex reserves.

As indicated by a recent IMF blog post, even before recent events “the share of US dollar reserves held by central banks fell to 59 percent – its lowest level in 25 years – during the fourth quarter of 2020”. The ‘winners’ have been other currencies including the Australian dollar, Canadian dollar, and Chinese Renminbi, which increased their share to 9% (Figure 14 – ‘Other’ line, in green).

This trend seems likely to continue. Indeed, the Bank of Israel recently decided to reduce USD and EUR holdings in favour of a higher weighting towards GBP, as well as new allocations to JPY, CAD, AUD and CNY. While such moves are incremental, they will likely add up over time.

More importantly, we believe the rush to implement sanctions against Russia by the US and Europe in early 2022 has further undermined any pretence of ‘US Dollar neutrality’. Over the last fifteen years, successive US administrations have sought to ‘weaponise’ the US Dollar in order to achieve their foreign policy goals.

The latest moves by the US and its allies have further pushed these boundaries, and we believe will likely lead to unintended consequences. As shown by the Faroe Islands’ surging salmon sales, sanctions rarely work as expected.

The decision to block several Russian banks from the SWIFT payments messaging system is notable.20 While this creates serious difficulties for these banks on the international stage, it also raises the likelihood that Russia and China will increasingly seek to rely on their domestic bank messaging systems – SFPS and CIPS – for transfers. In the future, Russia and China might well seek to encourage other trade partners to use these messaging systems.21 In effect, this would give the US less visibility and control over banking payments.

The most significant sanction by the US and its allies, however, was the decision to sanction the Bank of Russia, the first time in the modern era that any major central bank has faced such restrictions.22 These sanctions mean that Russia can no longer access around half of its US ~$640bn in forex reserves.23

The US expects that these sanctions will hit Russia’s economy hard, acting as a form of punishment and supposedly dissuading Russia from engaging in further military action in Ukraine.

This decision is particularly relevant for China, which holds US ~$3.2tn in forex reserves (of which slightly more than $1tn is invested in US Treasuries). These reserves reflect the large historic and ongoing bilateral trade relationship between the two countries. In recent years, however, tensions have been rising.

In a recent SCMP opinion piece, respected Chinese economist Yu Yongding wrote that “honouring debt obligations is one of the most important rules” in the international financial system, and that “freezing a country’s foreign exchange reserves is a blatant breach of that trust”.

Yu added, “The US, which issues the main global reserve currency, is jeopardising its financial credibility”. He did not offer a solution to safeguard China’s foreign assets, but did note that policymakers in China – and in other countries – would be “thinking very hard about solutions”.

Indeed, we think that the unintended consequences of abrogating Russia’s reserves – which some see as tantamount to selective default – are likely to be significant. This action against the Bank of Russia has sent a strong message to the world that forex reserves denominated in US Dollars or held in the banking systems of the US and its allies are no longer inviolable.24

It would be unsurprising to see strategic competitors to the US such as China now look to implement an effective freeze on further investment in US Treasuries, as well as possible divestment of existing assets in control of the US and its allies (i.e., de-dollarisation). These recent events will likely also provide an additional impetus for ‘non-aligned’ countries to think very carefully about their US Dollar exposures.

Coming at a time when the Fed is set to implement Quantitative Tightening, any trend towards de-dollarisation would place further upward pressure on US interest rates. The US Treasury will have to hope that, as in 2019, relative value hedge funds step up to buy more bonds.

Realistically, however, do China and other non-aligned nations currently have any alternative to the US Dollar?

Some individual and institutional investors believe that cryptocurrency provides the ultimate solution. While crypto might perform well for that reason, this market is probably still too small and with an insufficient track record to command the confidence of those allocating their country’s forex reserves.

Instead, we think that at present, gold is probably the only reserve asset with a market of sufficient size and standing to absorb the de-dollarisation reserve flows which seem set to increase in the coming months and years.

Even as Wall Street analysts worry about the possible impact of aggressive US interest rate rises on the precious metals market (given the negative historic correlation with real rates), we expect global central banks around the world to step in and ‘buy the dip’ on gold. At present, for those countries which might conceivably want to pursue their own independent foreign policy from the US, there would appear to be few liquid alternatives.

Macro Roadmap & Investment Views

The length of this ‘War and Peace’ letter perhaps attests to the degree of complexity and the many uncertainties which have emerged in the early months of 2022.

Below we summarise our current working macro roadmap and investment views:

China is in lockdown and economic activity has plunged – the economy is probably already in recession (although official data are unlikely ever to show this). The speed of the rebound will depend on how quickly lockdowns are lifted, but for political reasons, this is difficult to predict – not least because of the Party Congress in October 2022.

Given energy problems and other issues, Europe and the UK are likely to slip into recession soon. The US is probably the most resilient among all major economies, but is also already slowing even as the Fed starts to tighten monetary policy. A ‘soft landing’ will be extremely difficult to pull off, and it seems more likely that the Fed will overshoot the runway (and the economy).

Inflation in the developed world will likely soften as global economic activity slows, but we expect it to remain stubbornly higher than in recent cycles and to rebound fast in any recovery – the inflation genie is out of the bottle.

While the US Dollar has become overbought in the near-term, we still see a risk of a blow-off top in H2 2022-H1 2023 as monetary policy is tightened and liquidity stresses come to the fore.

Thereafter, it seems likely that de-dollarisation flows and other factors will contribute to a weaker US Dollar over a multi-year period during the mid- to late-2020s.

While commodities have already surged, we still see a risk of near-term blow-off top, especially if any exogenous shock or sanctions misstep causes funding stresses. In particular, we are watching energy markets.

Despite Wall Street worries that rising real rates will torpedo the price of precious metals, we think that central banks will buy any dip in gold as they look to diversify their holdings. As the global economy slows and tightening expectations fade, gold should also be a beneficiary. We remain more constructive on royalty companies and service providers than on miners, which are suffering from cost pressures.

Even if commodity prices do buckle in a downturn (especially industrial metals which are sensitive to economic growth), structural supply constraints suggest that commodities and resource stocks might still be leaders in the next cycle.

Even in a downturn, certain commodities with structural supply constraints (and vulnerabilities to supply disruptions) might remain surprisingly resilient.

Vulnerable Emerging and Frontier markets will probably be in for a rough ride in 2022-23, following in the footsteps of Sri Lanka and Pakistan. They will likely have to contend with a stronger US Dollar and higher interest rates, as well as surging food and fertiliser costs. Poverty and hunger will rise, and widespread political unrest seems inevitable.

China is at a crossroads – the closer that it hews to Russia, and the longer that regulatory repression and ‘Zero Covid’ lockdowns are sustained, then the more likely that the equity market rerates to a structurally-lower earnings multiple.

The equity markets of certain ‘non-aligned’ nations might be among the better performers in the 2020s, if their political leaders can successfully navigate the complex, emerging multipolar world.

As always, we reserve the right to change our minds on any of these points as the world changes around us!

We continue to believe that one of the best ways to invest during difficult periods is by sticking with companies with cash flow-generative business models and pricing power, as well as strong management teams who are able to cope well during uncertain times.

We wish all of you well in what is likely to be a difficult year.

Thank you for reading.

Andrew Limond

The original source material has been edited for spelling, punctuation, grammar and clarity. Photographs, illustrations, diagrams and references have been updated to ensure relevance. Copies of the original quarterly letter source material are available to investors on request.

See the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q1 2020 (published in April 2020) and the following Seraya Insight: ‘Covid-19 – the Catalyst for a Massive Shift in the Zeitgeist’.

For more information regarding our concerns on the energy markets, see the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q4 2021 and the following Seraya Insight: ‘Evaluating our Four Predictions for the 2020s & the Current Energy Crisis’.

European dependence on Russian gas supply varies by country; some nations are completely dependent on Russian imports.

‘Democratic Ideals and Reality, A Study in the Politics of Reconstruction’ (1919) by H.J.Mackinder (p.150).

‘Aleksandr Dugin's Foundations of Geopolitics’ by John B. Dunlop.

‘The Foundations of Geopolitics: The Geopolitical Future of Russia’ (1997) by Alexander Dugin.

There has been much debate in the Western media about how much President Xi knew of President Putin’s intention to invade Ukraine less than three weeks later – was he credulous or complicit? We have read plausible commentary arguing both viewpoints but have no particular insight. It’s probably more important, however, that China has decided to stand by Russia despite the invasion of Ukraine. Even if some in China are uncomfortable that the Ukraine invasion violates their own ‘non-interference’ principle, China has blamed the US and NATO expansion for the conflict. Absent a serious escalation in the Ukraine conflict (e.g., a use of nuclear weapons which might damage China’s standing with other nations), we see no reason for China to stop supporting Russia.

At some future date, it’s possible to imagine tensions growing over the two countries’ competing influence in Central Asia (e.g., Kazakhstan).

Over the last decade Russia has slashed its holdings of US Treasuries to almost zero while gold holdings have quadrupled to ~2,300t (Figure 12.1).

The ‘One Belt One Road’ initiative has proven to be more challenging in practice than in theory.

The Renminbi’s share of global payments currently stands at ~3% of the total, in 4th place behind USD, EUR + GBP.

This presentation is available on request.

This harks back to the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference attended by 44 nations at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire in July 1944. The delegates to the conference agreed on the shape of the international monetary system post-WW2. This lasted until the early-1970s and became known as the ‘Bretton Woods’ system.

‘The evolution of the Offshore US-Dollar System: past, present and four possible futures’ (2020) by Steffen Murau, Joe Rini and Armin Haas, Journal of Institutional Economics, 16, 767–783.

El Salvador and its problematic transition to Bitcoin as legal tender is not providing a persuasive model for those who might wish for widespread sovereign crypto adoption, i.e., Country E in Figure 11.3.

This was equivalent to RUB 155.5k/oz or US ~$1,520/oz on the day of the announcement, although would theoretically be worth as much as US ~$2,378/oz at the current Ruble to US Dollar forex rate.

Any infractions involving provision of military-use material to Russia would almost certainly trigger secondary US sanctions on Chinese companies, institutions and individuals. Memories of Trump’s Huawei ban are still fresh, and China is already experiencing an extremely challenging year in the wake of ongoing regulatory crackdowns and ‘Zero Covid’ lockdowns. With such a backdrop, and in advance of the Party Congress in October, it would be surprising if China were to risk incurring the wrath of the US by sending arms or ammunition to Russia.

As far as we are aware, there is only one precedent for a SWIFT ban – when Iranian banks were blocked from the system in 2012 following sanctions on the country’s nuclear program.

There have also been suggestions that Russia might attempt to use cryptocurrency for some payment cases (although the limited size of the crypto market makes this a challenge to implement at scale).

The US has in the past frozen the forex reserves of Iran, Syria, Venezuela and most recently Afghanistan (in early 2022 as the Taliban took over).

At present, Russia’s domestic gold holdings and Renminbi assets in China remain unaffected by the freeze, although there are attempts by the US to restrict trading of Russia’s gold holdings.

Several other actions by the US and its allies are also likely to have unintended consequences. One of these has been the recent targeting of Russian oligarchs under Western sanctions regimes, and the confiscation of their assets around the world based on apparently arbitrary decisions made by individual politicians (under sanctions and AML legislation) rather than according to any due process with a right to response. While such punitive measures might be politically popular, they set a worrying precedent for property rights and the rule of law. Another recent Canadian initiative in Feb 2022 was for the government to invoke the Emergency Act and freeze the bank accounts of protesters involved in the ‘Truckers Protests’ against Covid vaccine mandates in downtown Ottawa. Those providing funding to the protesters were also targeted. While many bank accounts were soon unfrozen, this move appears to have done lasting damage to the credibility of the Canadian government.