Uranium Update – A Tale of Two Markets

As the World Nuclear Association Symposium commences this week, a reminder why investors should refocus their attention on long-term supply and demand dynamics

This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

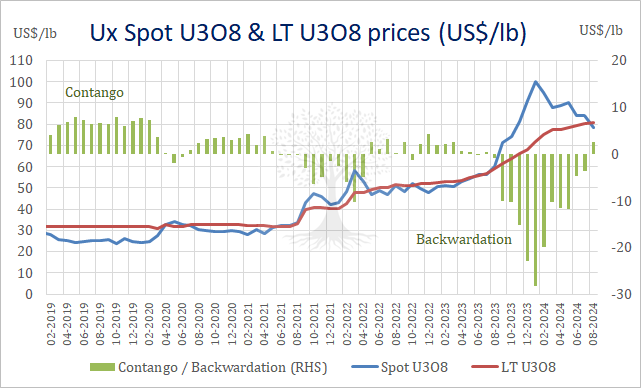

After a dramatic +91% run-up in 2023, the uranium spot price has consolidated in 2024. After briefly peaking above US$100/lb in January, the price of U3O8 for near-term delivery has settled back in a range of US ~$78-95/lb.1

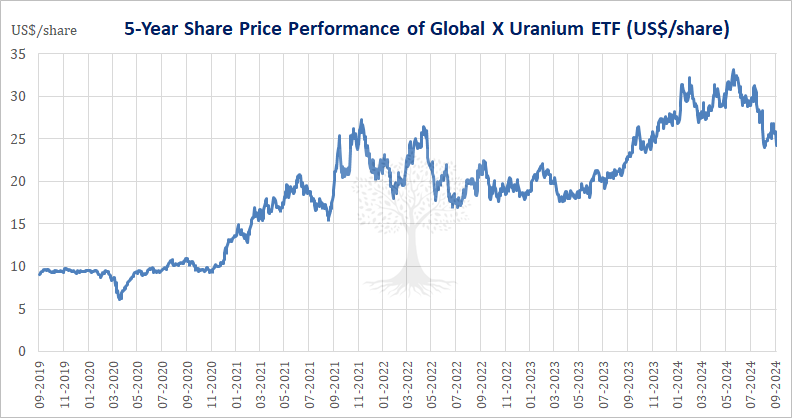

The spot market sell-off since January has in turn negatively impacted the price of listed uranium miners and developers (Figure 2), with the current stock valuations now implying an average long-term U3O8 price of just US ~$63/lb,2 a significant discount to current market prices.

While the uranium spot market tends to grab the headlines, however, the uranium ‘term market’ is telling a different story.

Spoiler alert! We think the next leg up in uranium prices will probably be driven by the realisation that uranium production costs are rapidly rising, and that a higher uranium price will be needed to incentivise more production to come online.3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Mixed Messages

First, let us briefly revisit and define the ‘two uranium markets’: the ‘spot market’ and the ‘term market’.

The ‘spot market’ is for contracts which typically specify a single uranium delivery within one year of the contract signing date (note that this represents a much longer ‘spot market’ period compared to other commodities). By contrast, the ‘term market’ is for contracts with one or more uranium deliveries which are scheduled to occur a year or more after the contract signing date.4

Historically, the vast majority of uranium transactions (>80% by volume) have occurred in the term market. For example, in the US in 2023, ~85% of volumes were purchased under term contracts, with only ~15% of volumes purchased via spot contracts. That said, many term contracts do include some underlying link or reference to the spot price (often with caps, floors, discounts, and premiums involved), which introduces a measure of circularity between the two markets.

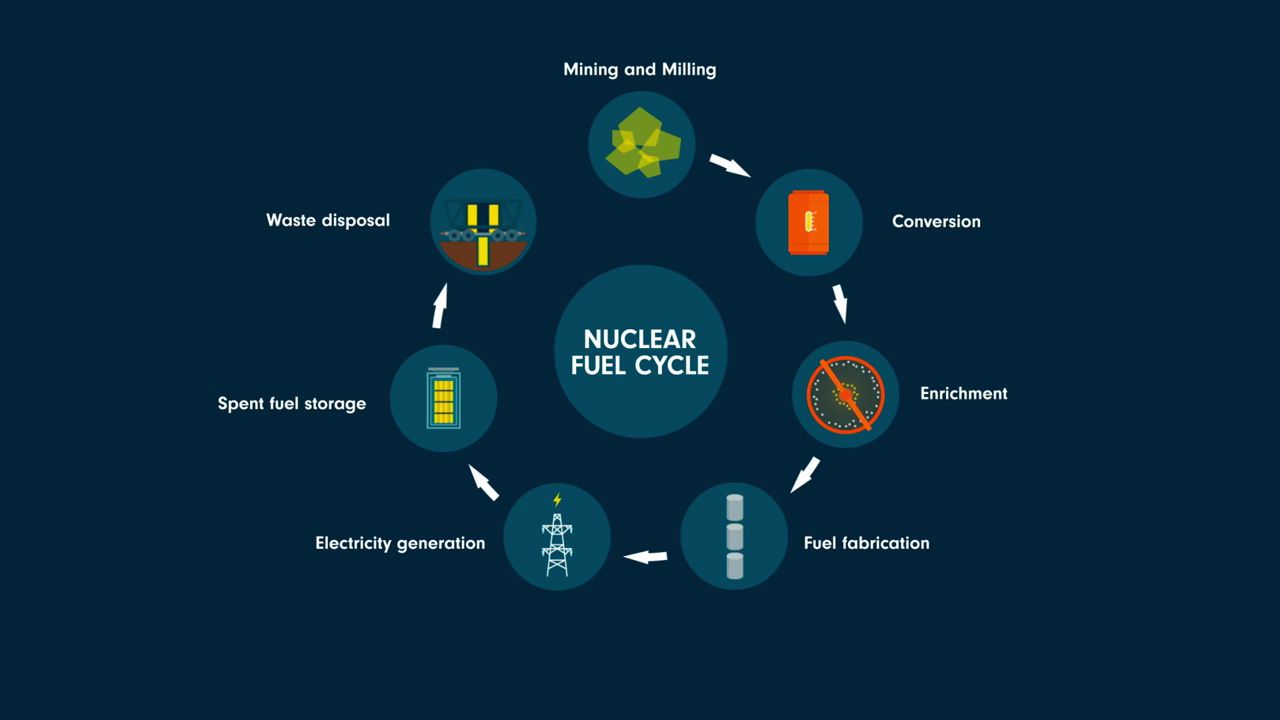

Security of supply is the critical feature in uranium procurement. This is because of the regulatory controls on this radioactive commodity, as well as the amount of time and number of steps involved in the complex nuclear fuel cycle (Figure 3). Power utility buyers of uranium typically contract separately for each stage in the process (i.e., mining, conversion, enrichment, and fuel rod fabrication), and it is critical that counterparts at each stage deliver reliably. Relying on spot market purchases for uranium would simply be too risky.

Unlike many other commodities, it is important to note that uranium does not trade on an open market. Buyers and sellers negotiate contracts privately. Whereas spot prices are reported daily, however, term prices are only reported monthly. Moreover, there is little visibility as to contract terms, with the lower end of procurement pricing bands typically reported as ‘the long-term price’ of uranium.

Pricing visibility thus perhaps explains investors’ preoccupation with the spot market as the primary source of price discovery, although in reality it often sends a confusing signal. So far in 2024, the spot price of uranium has fallen by -13.7%, while the long-term price has actually risen by +19.1%!5

Of course, the main reason for this deviation between the U3O8 spot price and long-term price is that the gap between these benchmarks has been narrowing after a period of marked divergence.

The price deviation commenced in mid-July 2023, with extreme market backwardation (an unusual occurrence in the uranium market) peaking in January 2024. More recently, the market has started to normalise, returning to a more usual contango price curve during August 2024 (Figure 4).

Last year, there seems to have been very little uranium readily available for purchase in the spot market. This catalysed a rush to buy, including from some financial investors. Meanwhile, utility buyers were loath to chase the spot price higher and lock in higher long-term prices. Uranium miners, on the other hand, have been expecting prices to move higher, and were thus only willing to contract for minimal volumes at ‘cheap’ long-term prices.

A standoff ensued, which resulted in a collapse of uranium contracting volumes. In H1 2024, there was only ~31mn lb of U3O8 contracting activity. While it is true that the first half of each calendar year tends to be a weaker seasonal period for long-term contracting activity, activity this year is particularly weak, and represents a -~73% fall in volumes compared to H1 2023.

It’s noteworthy that this contracting activity also represents just one-sixth of the more than 180mn lb in annual demand for uranium. This barely places a dent in long-term uranium supply deficits, and if this drought continues, it will mean that not enough new contracts are being signed to replace the older supply contracts which are rolling off.

In summary, spot prices ran ahead of themselves from mid-2023 to early 2024. This has now ‘normalised’, with spot and long-term prices converging.

What next?

Producers Are Facing Higher Costs!

The cost of production for uranium is rising rapidly. This appears to be the main reason that many uranium producers have been holding back on signing long-term contracts with utility customers. Given the tightness of supply, producers assume that the longer they wait, the stronger their negotiating power should become.

The rapidly increasing cost of production is not just a negotiating point! Producers can now point to an increasing number of concrete real-world examples.

First up, Kazatomprom, the largest primary producer of uranium in the world:

In February 2024, Kazatomprom reduced its 2024 production guidance from -10% to -20% versus its subsoil use contracts level (Figure 5).6 This was primarily due to a shortage of sulfuric acid, a key raw material input in the ISL mining process. Kazatomprom does have plans to build a sulfuric acid plant in order to address this issue, but this plant won’t come online until 2027, which suggests production issues will still be with us for several years.

In July 2024, Kazatomprom unexpectedly announced a significant increase in the mineral extraction taxes payable to the government of Kazakhstan. The big step-up will come in 2026, when the mineral extraction taxes payable by the company will depend on both the annual production volume from each of its mining operations, as well as the price of uranium.

As a result of the increase in the mineral extraction taxes, as well as the scarcity of sulfuric acid, Kazatomprom’s C1 cash cost guidance for 2024 has risen to US ~$16.50-18.00/lb, +24-36% higher than the company’s actual 2023 C1 cash cost.

On 23 August 2024, Kazatomprom announced a significant downward revision to its 2025 production guidance, from a previous estimate of 79.3-81.9mn lb, to a new estimate of 65.0-68.9mn lb.7 These revised production numbers represent a growth rate of just ~+12% compared to 2024 production guidance, lower than market expectations. The reasons given for the reduced guidance were continued uncertainty in relation to sulfuric acid procurement, as well as construction delays at one of the company’s operations (JV Budenovskoye).

Rising production costs are not just restricted to Kazatomprom! Various other important producers are also reporting capex and cost inflation issues:

In March 2024, ASX-listed Paladin Energy recommenced commercial production at their Langer Heinrich Mine in Namibia (Figure 6), with the first customer shipment completed in July 2024. Production cost guidance for FY2025 (i.e. the ramp-up phase of operations) has been updated to US ~$28-31/lb, which is +26-39% higher than cost projections for the company’s original restart plan from November 2021.

On 1 August 2024, NexGen Energy provided investors with an update on the economics for their flagship Rook I project. Both the estimated capex and opex over the life of mine have increased significantly, from US$975mn and US$5.69/lb (as set out in the company’s March 2021 feasibility study) to US$1.58bn and US$9.98/lb respectively (as per the most recent study).

Judging from these announcements, as well as our recent conversations with uranium miners and developers, we believe that the incentive cost of production for uranium has already moved towards US ~$100/lb!

We believe that soon enough, prices in the three-figure range will likely be needed for miners to bring on new primary production.8 This is even without assuming any large increase in reactor rollouts, or adoption of new nuclear technology such as Small Modular Reactors.

Geopolitical Risks

It is not just escalating cost pressures which are affecting the uranium miners. Geopolitical risks are also growing.

Niger has historically been the world’s third largest uranium producer (with ~5% of global output). Significant uncertainties emerged following a coup d'état in Niger in July 2023, and in recent months these fears have played out (Figure 7).

In June 2024, Niger’s military government revoked Orano’s operating license for its Imouraren deposit in the country. This was followed soon after by the decision to withdraw GoviEx Uranium’s mining permit for the Madaouela deposit. There has also been significant uncertainty around Global Atomic’s Dasa Project in Niger, despite the company’s recent announcement of government support for the project.

Neither Imouraren nor Madaouela, both of which are higher-cost projects, were expected to go into production soon. Dasa was expected to commence production in 2026, but that might now be delayed given that there are now higher risks involved with funding this project.

Overall, the events in Niger underline the significant supply risks faced by the yellow metal. It’s difficult to avoid the fact that a significant amount of uranium production comes from jurisdictions with higher levels of geopolitical risk.

The major geopolitical event of the first half of this decade has been the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which commenced in early 2022. Increased US-Russia tensions in the wake of this invasion have now finally resulted in action to reduce US dependence on uranium shipped from Russia.

In May 2024, President Biden signed bipartisan legislation to ban the import of low-enriched uranium products from Russia, effective 11 August 2024. This was a significant move, as around one-third of enriched uranium used in US nuclear reactors is imported from Russia.

Given the magnitude of the decision, the US Department of Energy (‘DoE’) has created a waiver process to allow some imports from Russia to continue for a limited time, through 1 January 2028 at the latest. During this period, the expectation is for the US to expand its own domestic uranium conversion and enrichment facilities.

We believe that this move to restrict Russian important will eventually lead to a bifurcated market for uranium (the West and the Rest), as was the case in the 1990s and before. In this case, uranium in the Western world would likely trade at far higher prices than in Russia and its nuclear clients.

Right now, however, the US ban on Russian uranium and waiver situation has created significant uncertainty for buyers in the long-term uranium contracting market. In particular, a lack of clarity in the enrichment market would appear to be an important reason why contracting activity across the uranium fuel cycle dried up in mid-2024. As and when there is more clarity on the DoE waivers and alternative uranium enrichment strategies, likely in late 2024, we would expect contracting activity to pick up.

Demand Remains Robust

Meanwhile, demand for nuclear energy is alive and well.

In June 2024, US Congress passed the ADVANCE Act (‘Accelerating Deployment of Versatile, Advanced Nuclear for Clean Energy’). This was designed to enhance ‘US nuclear leadership and security’ through a wide range of measures, including support for existing nuclear generation capacity, promoting the deployment of advanced nuclear technologies, expanding the overall US nuclear supply chain, and streamlining the licensing process for nuclear energy.

In August 2024, China announced the approval of a record 11 new nuclear reactors, which are to be constructed over the next five years. Note that China approved ten new reactors each year in 2022 and 2023, and the country now seems to be accelerating its buildout. As part of our original thesis investment for uranium, we expected to see China increase its dependence on nuclear power, to diversify away from its heavy dependence on coal.

On a separate note, the Artificial Intelligence (‘AI’) theme has been front and centre of financial markets in 2023 and 2024. Investors have also realised that AI represents a massive energy demand story (Figure 8).

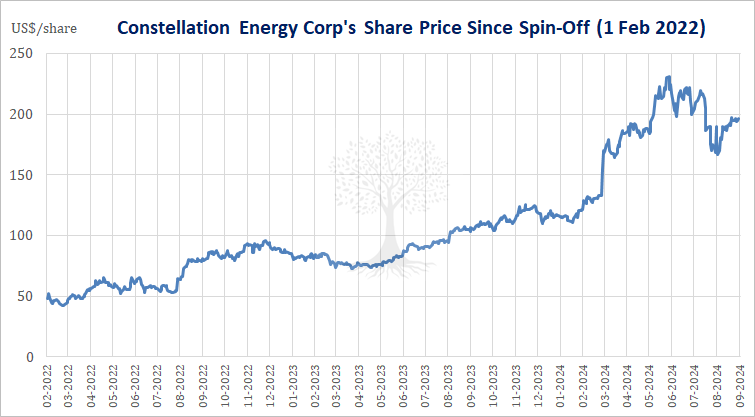

One only has to take a look at the stock price of nuclear-heavy US utility Constellation Energy over the past year (Figure 9) to realise that nuclear energy is likely to be the key beneficiary of the surge in AI-driven data centre capex.

Nuclear power for AI is a trend which is being driven by the large tech companies themselves, as the emergence of AI has put at risk the decarbonisation goals which are so important for them and their customers.

It is still unclear how much AI-related demand might add to overall nuclear energy demand over the long term, but not much is factored into most uranium demand forecasts today.

We still see the main potential risk to demand from a major ‘nuclear incident’ which might increase concerns about the safety of nuclear power.

Sentiment around nuclear power, which has been improving, would no doubt be badly affected by another nuclear accident (such as the tragic Fukushima Daiichi accident in 2011) or by a potential war-related incident. For instance, there are concerns over the safety of Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant, which is located on the front line of the Russia-Ukraine war (Figure 10).

Explaining Spot Market Weakness

Given that the fundamentals and outlook for uranium appear to be strong, why has the U3O8 spot price been so weak?

As a reminder, the spot market only represents a small percentage of total uranium trading activity each year. In reality, the spot market is a thin, low-volume market which is mostly driven by traders rather than long-term demand fundamentals. It is also the place where certain producers sometimes offload small amounts of uncommitted uranium production that do not have a long-term buyer.

As a result, spot price weakness over shorter periods of time might be attributable to a variety of factors, including more general energy market weakness (which has been the case in 2024), seasonality, uncertainty (e.g., the uncertain waiver situation around the impending US ban on Russian uranium imports), as well as a lack of financial buyers.

Indeed, investment by financial buyers (or ‘speculators’!) has been an important driver of the uranium market in recent years. In particular, the Sprott Physical Uranium Trust (‘SPUT’) – which took over from Uranium Participation Corporation in 2021, modified its structure, and was then able to grow its AUM from US $630mn to US ~$5.2bn currently – has been a significant source of financial demand for uranium, particularly at certain key moments.

The mechanics of SPUT are such that when its shares trade at a premium to its NAV, the trust is permitted to raise capital by issuing shares to fund additional uranium purchases. In the first half of 2024, however, SPUT has only traded at a premium for five of 126 trading days, and so the trust has made limited spot market purchases (a total of ~2.3mn lb). This compares to a total of 18mn lb of SPUT purchases in 2022.

It's also worth noting that SPUT made only modest uranium purchases in 2023 (~3.9mn lb). Given that the spot price still increased significantly over the course of last year, this might be a sign of just how tight the spot market is getting. In other words, even relatively small volumes were able to move the uranium price meaningfully.

Conclusion

In summary, although the spot market can be a powerful driver of sentiment, it is less important for the direction of the uranium market than long-term supply and demand dynamics. Investors would thus be well advised to focus their attention on the term market and on the uranium price curve (which has returned to contango).

There is a positive backdrop for the long-term uranium price, which is being driven steadily higher by growing worries over the security of supply, as well as rising costs for producers. Utilities are also still not yet signing contracts at a sufficient pace to meet the replacement rate for their contracts which are rolling off.

This suggests the bull market for uranium is still not yet done!

Thank you for reading.

Varun Dutt, Andrew Limond

For publicly available uranium price data through August 2024, please refer to the website of uranium major Cameco (which publishes the average of UxC and TradeTech month-end prices).

This average ‘implied price’ is based on analysis by Canaccord Genuity across their listed uranium equity coverage universe. The implied price states the effective long-term uranium price derived from the current share price of a uranium producer, based on a discounted cash flow model.

Thanks to Alex M of Eightstone for his insights and contributions to this Insight.

The ‘term market’ can be further be broken down into the ‘mid-term market’, for deliveries within one to three years, and the ‘long-term market’, for deliveries three years or more later.

Pricing data from 1 Jan through 31 August 2024 is from Cameco’s website (and represents an average of the month-end prices published by UxC and TradeTech).

In Kazakhstan, subsoil users are granted rights from the government for the exploration and/or production of minerals. These agreements are subject to various terms and conditions, including minimum production levels. Some flexibility, however, is allowed (albeit still subject to regulatory approval) in order to align with current market conditions, operational constraints, and/or contractual commitments.

Or, as per Kazatomprom’s disclosure, from 30,500-31,500 tU to 25,000-26,500 tU (assuming a conversion ratio of 2.5998lb to 1 kgU).

A quick note on secondary supply, which has been an important additional source of supply in recent years. Secondary supply includes uranium generated by underfeeding during the uranium enrichment process, recycled uranium from used fuel, mixed oxide fuel and re-enriched depleted uranium tails. Without going into too much detail here, these secondary sources of supply are expected to play a gradually diminishing role in the uranium market. The World Nuclear Association estimates that these will go from ~11-14% of reactor requirements currently, to as little as 4% by 2050.