This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

In Part 1 of this special two-part Insight, we watch Japan give a collective yawn as the Nikkei 225 Index hits a new high, puzzle over the Japanese government’s obsession with a ‘virtuous wage-price cycle’, take a brief look at Japan’s failure to implement structural reforms, and outline some good reasons to buy Japanese stocks anyway.

In Part 2 of this special two-part Insight, we cover the ‘Not China’ trade, summarise what sectors and stocks performed best as foreign investors piled into the Japanese equity market in 2023, and outline where we think the best investment opportunities can now be found.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Japan Yawns as the Nikkei 225 Index Hits a New High

It was a miserable cold and rainy day in Tokyo in late February this year when the Nikkei 225 Index hit a new all-time high.

On the day of the new stock market record, I was plodding around the city meeting companies, accompanied by a veteran Japanese stock market broker. He had first started trading Japanese stocks back in 1982, and then spent much of the legendary 1980s ‘Bubble Era’ in Tokyo.1

Given that he and the rest of Japan had been waiting precisely thirty-four years, one month and twenty-four days2 for the index to surpass the old high of 38,915 (reached on the last trading day of 1989), and that the index had rallied +49.1% since the start of 2023, we vaguely hoped that a celebration might be in order.

On Thursday 22 February, as the market powered up into the close, we were visiting a company based in Gotenyama. Our counterparts were vaguely amused when we mentioned the new record close for the Nikkei 225 Index. Then they politely shrugged, and we carried on with the meeting.

There were no fireworks displays over Roppongi that night. Neither did there seem to be any more salarymen than usual out drinking in Shinjuku or Shibaura.3 Japan greeted the new record with a large, collective yawn. Even the successive index highs for the next month solicited little enthusiasm. Nobody seemed to care…

Why the lack of excitement?!

Maybe it was the weak Yen (which had depreciated by -7.04% against the US Dollar in 2023, and -12.2% in 2022)? Doubtful, given that the Yen is their home currency!

Maybe Japanese retail investors were waiting for the broader, market-cap weighted TOPIX Index to break out to all-time highs as well?4 Seriously unlikely!

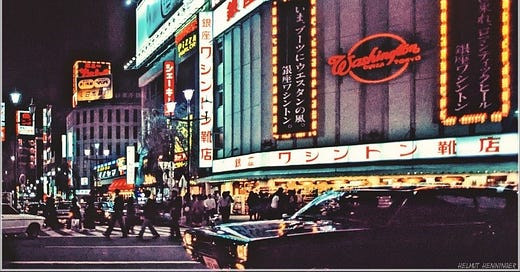

Back at the peak in 1989, when the land under the Imperial Palace in Tokyo was famously worth more than all land in California and Japanese consumer electronics companies ruled the world (Figure 2), Japanese stocks represented close to half of all global market capitalisation.

These days, after at least one ‘lost decade’ and a slow recovery, Japan is a very different place from the country that was tipped to be ‘Number One’. Japanese equities now account for just ~5% of world market cap, around one-tenth of the 1989 high-water mark.

Most importantly, we think that the reason why the new highs in the Nikkei 225 were largely ignored is that very few Japanese own their own equity market.5 There is an entire generation in Japan which has known nothing but pain and suffering from buying stocks. For most of the last three decades, it has proven too easy to lose money by investing in Japanese equities, and the older generation find it hard to imagine that this might change. (The younger generation, however, does seem to have a different mindset.)6

Several months earlier, at a Tokyo retail investor presentation held by one of the large Japanese brokerage firms, a salesman made a pitch to persuade more Japanese investors to allocate their capital to domestic equities. The Nippon Individual Savings Account (‘NISA’), a Japanese tax-advantaged investment scheme launched in 2014, was set to be expanded in January 2024 with a new higher annual investment limit and an unlimited tax-saving period. “Surely it would make sense,” he asked in vain, “To buy more cheap Japanese stocks in your newly expanded NISA accounts?!”

The Japanese retail investors were having none of it. An elderly gentleman at the back of the hall stood up and spoke his mind, “You must be joking? Do you seriously think we’re going to come in and buy all the stocks that the foreigners have already bid up?!”7

He had a point! The +28.2% rise in the Nikkei 225 Index (and +25.1% rise in the TOPIX index) in 2023 was driven by JPY ~3.5tr of foreign net inflows to the Japanese equity market.8 Foreign investors not only bought all the JPY ~3.0tr in stocks that Japanese households sold over the course of the year and more, they then also followed up with a further JPY ~1.5tr of net purchases in the first three months of 2024.

But what is the economic backdrop to this tremendous stock rally?

A ‘Virtuous Wage-Price Cycle’?!

After our meeting in Gotenyama, we jumped in a taxi. Playing on the video screen embedded in the back of the passenger seat was the same advertisement, produced by the Japanese Cabinet Office, which had been playing all week in every taxi that we rode in.9

The government was clearly trying to send a message…

A young man bursts into the office of an ineffectual bucho (department head) in a generic Japanese office: “Give me a pay rise or I’ll quit my job!”

The bucho, looking horrified, asks the audience: “What should I do?”

Thankfully, help is on hand in the form of a young, waiflike actress dressed as an angel who floats onto the screen: “That’s okay, the government says you can negotiate price rises with customers and then increase the salary of your employees!” [Smile!]

Cut to the bucho at a client’s office trying to negotiate a price rise for the first time in his life: “Er, our costs are up, please could I increase prices?”

The customer looks shocked until the anaemic angel – sent by the Cabinet Office – once again saves the day: “That’s okay, costs have risen and it’s fine to accept price rises!” [Bigger smile!]

The bucho, proud of his work, returns to his own company and agrees to increase the salary of his insubordinate subordinate: “Yoshi! Did it!”

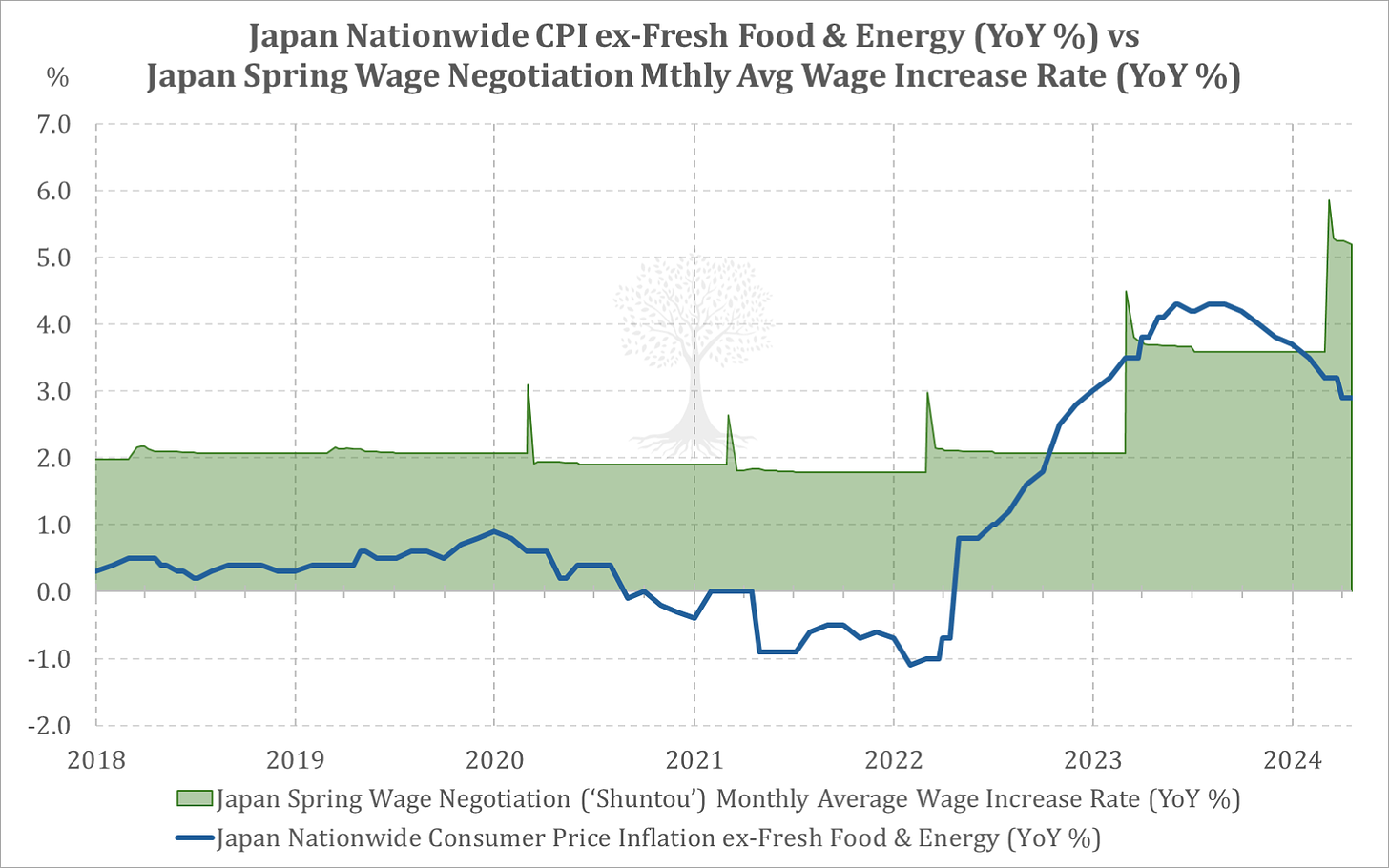

In the last couple of years, consumer price inflation in Japan has reached levels not seen since the early 1980s (Figure 3). Just like elsewhere in the world, there are several different schools of thought regarding the reasons behind the inflationary surge and whether it will persist.

In the first group – ‘Team Transitory’ – we find the majority of officials from the Bank of Japan (‘BoJ’) along with most Japanese sell-side economists and the Nikkei newspaper. They see Japan’s higher prices as cost-push inflation, driven at first by supply chain disruptions overseas and then by a much weaker Yen. They believe that these temporary factors will cease soon, inflation will subside, and Japan will revert to its enduring ‘deflationary malaise’. They remember policy missteps in years past and are terrified of tightening too early this cycle.

The second group, ‘Team Persistent’, is populated by a motley assortment of independent economists (and foreign fund managers).10 They believe that as more Japanese Baby Boomers retire and the labour pool shrinks, wages are finally being driven higher (Figure 3). Japanese companies are finally daring to raise prices, just as consumers are becoming much more tolerant of price increases. ‘Team Persistent’ thus sees current price trends as structural in nature, and inflation as more likely to be sticky.

The third viewpoint is that of the Japanese leadership (supported by some officials in the BoJ and MoF).11 They seem to be worried that higher inflation in recent years has been caused by cost-push factors, but they are so determined to exit ‘chronic deflation’ that they are willing to do whatever it takes to kickstart a ‘virtuous wage-price cycle’. Hence the cute commercials showing in the back of every taxi driving around Tokyo.

Unfortunately, the notion of a ‘virtuous wage-price cycle’ is misguided. Without productivity growth, there can be no wage gains for workers in real terms. In other words, any salary gains will just be eaten up by higher prices paid for goods and services, which sounds distinctly unvirtuous to us. Productivity gains are thus essential to avoid a government-endorsed inflationary spiral!

In the last couple of decades, productivity in Japan has stagnated, and has recently declined to new lows. In this era of worker shortages, however, it’s not hard to imagine how companies will have to accelerate labour-saving investments. Indeed, one of the reasons for poor productivity in Japan has been a lack of domestic investment over the last two decades. A long overdue shift to digitalisation in Japan is also now in process. More domestic capex, including IT investment, should help to boost productivity in Japan, although to what extent and when is still uncertain.

We find it harder to imagine, however, that Japan will embrace the other productivity-enhancing reforms that it has shirked for years.

The Real Problem: Reform Failure

Over the last several decades, it has been more convenient for the Japanese establishment to obsess about ‘structural deflation’ rather than facing the real problem: their chronic inability to implement supply-side reforms.12

Your correspondent first arrived in Japan after the deflationary ‘Lost Decade’ of the 1990s. He then cut his teeth in the Japanese market during a period of true optimism over reform. This was the reign of ‘maverick’ Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi, which spanned 2001-2006 (Figure 5).

The reforms during this period were tangible. Prime Minister Koizumi and Heizo Takenaka13 recapitalised the banks to fix the country’s prolonged banking crisis. After much drama, they also managed to privatise Japan Post in a valiant attempt to curtail pork-barrel politics.

That marked the high point of reform, however. Thereafter, the Japanese establishment closed ranks before Mr Koizumi could move onto key reforms in areas such as the tax system, medical services, pensions, limits on public works spending, reform of other public corporations and the labour market. Reforms in most of these areas are yet to be implemented, with the country’s two-tier labour market in need of particular attention.

The next real attempt at reform in Japan came with the ascension of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe14 (who served a second term as Prime Minister during the period 2012-2020). His economic plan was designated ‘Abenomics’ and consisted of ‘three arrows’: (1) monetary easing; (2) fiscal stimulus; and (3) structural reform.

The first two arrows flew from the bow, especially the BoJ’s massive monetary easing program (although we have questioned its true efficacy). The third arrow, however, badly misfired, with few effective structural reforms really being implemented.

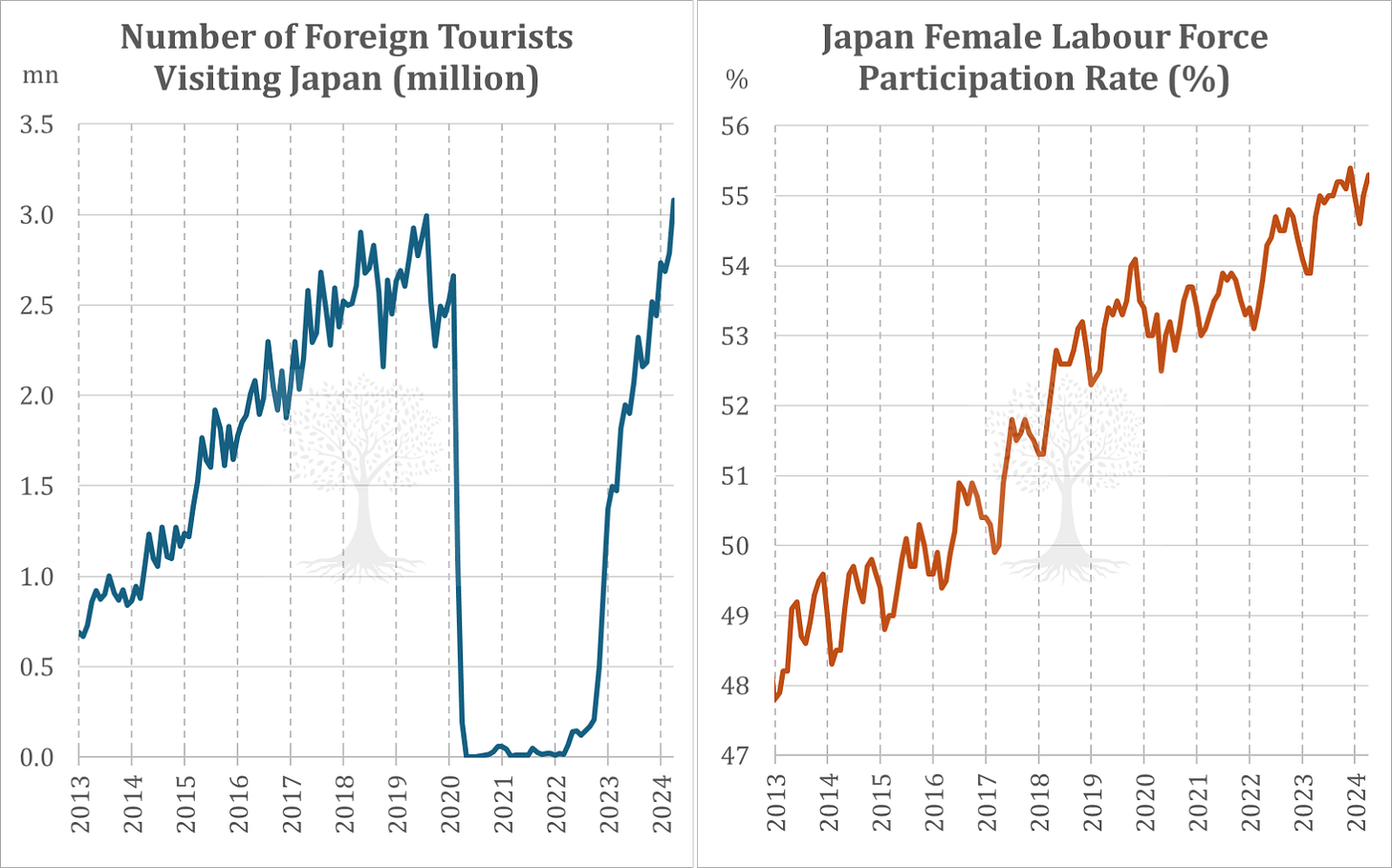

Instead, the economy muddled by with a little help from a massive tourism boom (Figure 7.1), which both used up slack in the economy and helped prompt new modernising investment in various domestic sectors such as retail, transport and leisure.15

The tightening in the labour market during the Abe era was at first disguised by a massive jump in the female labour participation rate, from ~48% in 2013 to >55% by 2023, surpassing the US (Figure 7.2). An increasing number of retirees being employed on part-time contracts also helped boost the size of the labour pool, albeit temporarily.

These days, it’s almost impossible to conduct a company meeting in Japan without discussing labour shortages of skilled workers. This now ranks as the top concern for most company executives with whom we speak. These labour shortages are driving up both wages and prices.

As a result, Japan’s famous long-standing resistance to accepting foreign labour is starting to crack. Convenience stores and construction sites are already brimming with foreign workers. We expect to see much more immigration to Japan in the coming years.

During the Abenomics era, investors were also happily ‘bought off’ by corporate governance improvements. The flagship reform in this area was the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s (‘TSE’) Corporate Governance Code, which was first introduced in 2015 (and was then revised in 2018 and 2021).

This had the happy effect of encouraging companies to focus more on minority shareholders, which led to higher dividend payouts and more share buybacks. It also led to a reduction in cross-shareholdings and a rationalisation of listed subsidiaries (i.e., disposals or buy-ins).

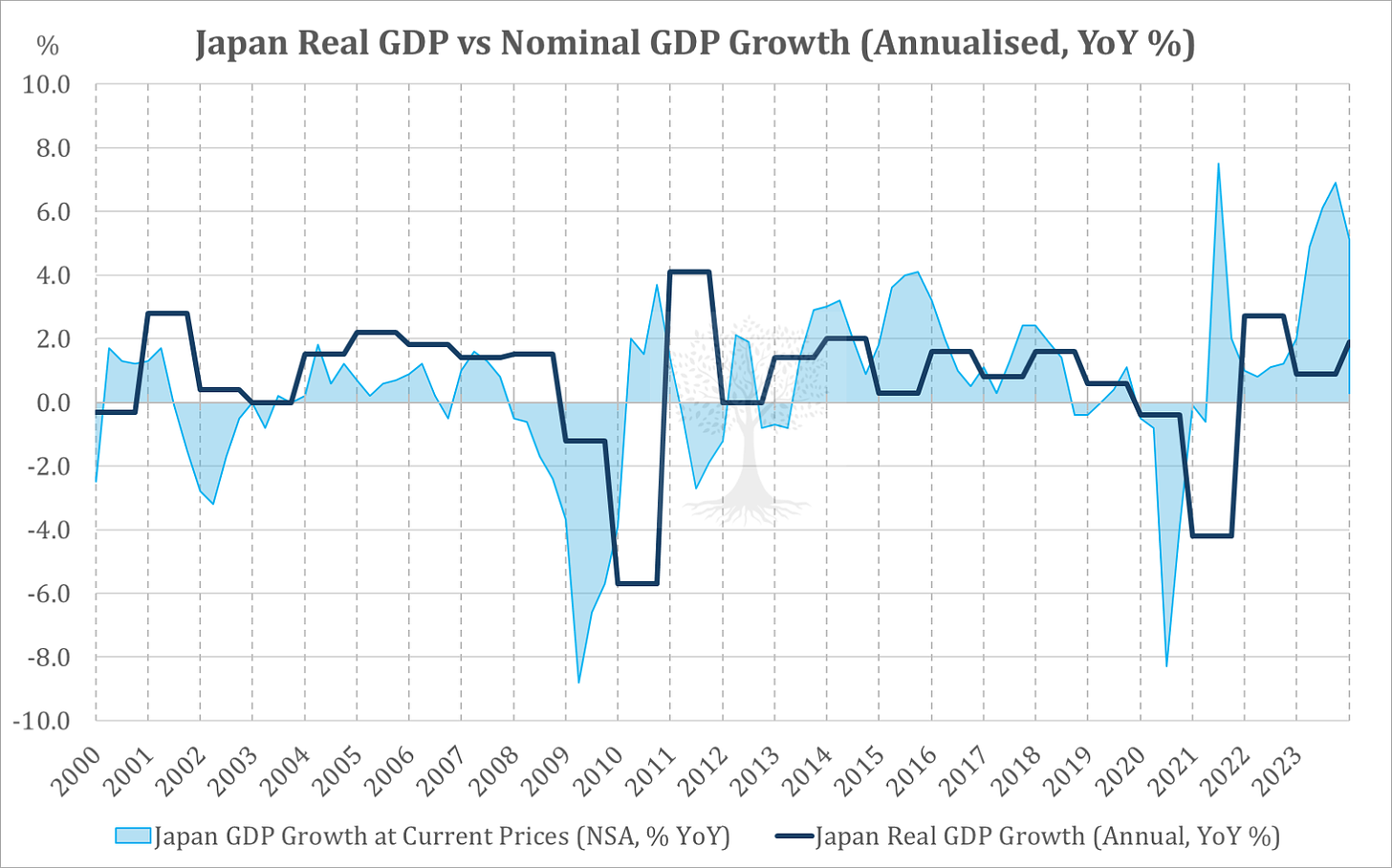

The net result of all these developments in Japan over the last decade has been a somewhat curious cocktail of moribund real GDP growth (fluctuating around +0.5% per annum, as shown in Figure 8), rising inflation, massive government debt (gross debt-to-GDP now stands at ~248%), a buoyant stock market, and cash interest rates which are still close to zero percent.

Given inflationary trends and wage growth at >5%, Japan’s interest rates should rightfully now be closer to 2-3% rather than zero, but political and debt-related considerations16 are delaying the necessary adjustment.

This post-Koizumi scorecard shouldn’t make economists very happy. We are investors, however, and we still see plenty of reasons for optimism!

Reasons to Buy Japanese Stocks

In particular, we would like to draw attention to the following points:17

Japan is finally enjoying strong positive nominal GDP growth. This represents a massive shift in the Zeitgeist for Japan - the importance of this development should not be underestimated! Note that company revenues and profits are recorded as absolute nominal figures, not in real (inflation-adjusted) terms. It is thus nominal growth which matters more for stocks. In 2023, Japan had nominal GDP growth of >5%, which was higher than nominal GDP growth in China. Positive mid-single digit nominal GDP growth in Japan should finally provide a tailwind for corporate revenue growth.

The trend towards better shareholder returns, including higher dividends and more share buybacks, has taken root in corporate Japan. In virtually every company meeting we attend these days, management feels obliged to bring up the topic of shareholder returns and explain what they are doing on behalf of minority shareholders. This represents a massive shift compared to the situation in Japan 5-10 years ago.

Low valuations for the Japanese market as a whole, even after the 2023 rally, mean that there is ample scope for rerating. If interest rates – real and nominal – remain too low in Japan, as seems likely, then there is a chance that valuations rerate much higher if Japanese investors ever decide to buy their own market! We are hopeful this will happen – there is currently a generational shift underway, and older Japanese investors who have known nothing but pain from the equity market are being replaced by younger risk-takers who are more willing to trade stocks.

Various reforms are underway which should incentivise more domestic M&A activity, including unsolicited bids for companies. This could very well allow more value realisation through takeovers; a lack of such activity in the past was arguably one factor which depressed valuations in the Japanese stock market.

Banks in Japan finally have incentives and confidence to lend. Nationwide land prices bottomed out in 2016 (earlier for Tokyo), with land price rises accelerating recently. This should theoretically give the banking sector more confidence in collateral values for loans. The Japanese yield curve has also steepened following the relaxation of the BoJ’s yield curve control, meaning that lending is more profitable than it has been in years for the banks (but still cheap for borrowers). All that is needed now is more confidence to borrow!

Japan is an inefficient market with ~4,000 listed stocks and patchy analyst coverage. As we never tire of saying, market inefficiencies = opportunities. Despite a moribund broader economy, Japan’s corporate sector is also very dynamic and boasts a critical mass of companies which are globally competitive in their own niches. There are also various tailwinds for certain areas of the market, for example those companies benefitting from ‘themes’ such as Demographics, Digitalisation and Domestic capex (the three ‘D’s).

The Japanese Yen is the least expensive major currency in the world right now. Indeed, the currency is just about cheaper than it has even been on a real effective exchange rate basis. It is entirely possible that the Yen will continue to weaken in the near-term if interest rate differentials with the rest of the world (especially the US) do not narrow. Nevertheless, Japan’s current account is in comfortable surplus, and it is hard to imagine how interest rate differentials can widen further in the near-term. We thus expect a snapback towards Yen strength at some point this year.

Based on this analysis, one might have expected that the best performers in Japan during the recent rally would have been a selection of niche champions which enjoy strong revenue growth, pricing power, good cost controls (especially for labour), improving corporate governance and idiosyncratic tailwinds.

In fact, this is precisely what has not happened.

In Part 2 of this special Insight on Japan, we look at which stocks have performed the best since the start of the rally in early 2023, and where we think the best investment opportunities can now be found.

Thank you for reading.

Andrew Limond

Many thanks to RARM and his colleagues for their support and wise counsel on Japanese stocks.

Or 12,473 days.

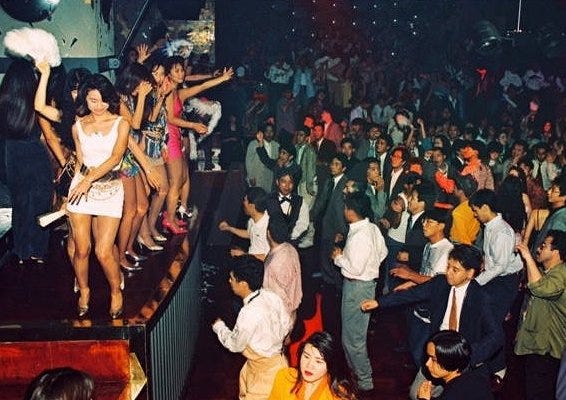

Sadly, Juliana’s, the legendary late Bubble Era nightclub, closed down 20 years ago, so we couldn’t go there to celebrate.

As of the date of this Insight, the TOPIX Index has not quite yet managed to break out to new highs (although it is close).

At end-2023, only 12.9% of Japanese household assets were invested in equities, with almost 53% of savings in cash. While this small proportion of Japanese household assets invested in equities does represent an increase relative to the previous year, it is still a long way from the ~40% of US households assets which are allocated to stocks.

Many thanks to DM for his contributions to this Insight.

Much of the NISA flows have been invested into foreign stocks and funds rather than the Japanese market.

In comparison, there were almost JPY 25tr of foreign net inflows to Japanese equities during the first three years of Abenomics (from 2013). These inflows then completely exited the country over the next five years.

The content of the commercial is described as remembered; the main message holds although details may differ!

These independent economists include Tsutomu Watanabe, Professor of Economics at the University of Tokyo, whose analysis served as the inspiration for this section of our Insight.

Intriguingly, this group might well also include the new BoJ Governor Kazuo Ueda. There are some hints that Governor Ueda believes that ‘this time is different’ and inflation is finally returning to Japan.

Many thanks to GCB for his erudite economic analysis, which served as the basis for this section of our Insight.

Heizo Takenaka served as Minister of State for Financial Services and head of the Financial Services Agency under Prime Minister Koizumi.

Prime Minister Abe, Japan’s longest-serving premier, was tragically assassinated in July 2022. May he rest in peace.

Inbound tourist numbers have rebounded, with visits to Japan now at record highs of >3mn per month. Inbound tourism is thus once again an important macro factor for Japan.

Policymakers remember past policy errors (involving premature monetary and fiscal tightening in previous cycles) and are afraid of tightening too early. Japan would also rather not be paying higher interest rates on its massive debt load. In reality, however, a slow increase in interest rates would first boost private sector interest income (given high levels of corporate and household cash savings), before gradual debt refinancing requirements would slowly force the government to make difficult decisions regarding spending cuts for the pension and welfare system.

For the background to the first four points of this analysis, please refer to our ‘matrix of equity returns’ which appears in the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q2 2019, as well as the following Seraya Insight: ‘Why invest in Asia? A Fundamental Look at the Drivers of Growth and Stock Returns in Asia since 1960’.