‘Growth in Value’: Investing in Value Stocks with 'Hidden' Growth Assets

Searching for value among stocks with hidden growth investments: three case studies

This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

This Insight is an extract adapted from the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q3 2021.1

One of the most notable features of the US-led global equity bull market since 2009 has been the massive outperformance of ‘growth’ stocks versus ‘value’ stocks (Figure 1).

The most appropriate definitions for ‘growth’ and ‘value’ are debatable. Most ‘value’ indices focus on simplistic valuation metrics such as price-to-book ratios, rather than taking a more holistic approach and considering earnings power and cash flows.

Nevertheless, few would disagree that value investors who have stuck to a more traditional ‘Graham & Dodd’ style of security selection over the last decade have dramatically underperformed other investors who were willing to buy stocks with higher growth prospects, even if these growth stocks traded at much richer valuation multiples.2

Aggressive central bank stimulus has no doubt had a large part to play in driving this phenomenon. Massive liquidity provision has meant more money chasing fewer opportunities. Central bank largesse has also facilitated a greater financialisation of society, benefitting asset-owners at the expense of wage-earners.

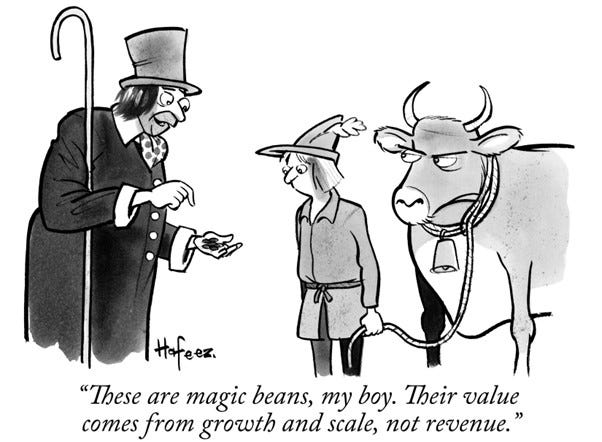

As interest rates – and opportunity costs – have been driven ever lower over the last generation, investors have been willing to suspend their collective disbelief, defer cash flow gratification into the future, and buy growth!

As growth and venture capital (‘VC’) investing has flourished at the expense of dividend- and balance sheet-oriented capital allocation, the valuation metric of choice has evolved from a multiple of cash flow to multiple of sales.

The massive amounts of capital deployed towards ‘disruptive’ companies have enabled these start-ups to undermine ‘old economy’ business models in media, retail, and most other sectors too.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Case Study: Vietnamese ‘Merchant Bank’ with Fintech Investments

Case Study: Japanese E-commerce Company with Southeast Asian ‘Growth’ Investments

What’s a ‘Value Investor’ to Do?

Over the last decade, life has not been easy for those who still care about investing with a sufficient ‘margin of safety’. Value investors have not only needed to avoid cheaper old economy stocks (which for the most part are perceived to have been ‘disrupted’ and so stay cheap) but also to find good companies trading at reasonable valuations.

This task has been particularly challenging in markets such as the US, where passive flows and other factors have driven up equity valuations to historically elevated levels. In certain popular sub-sectors of the stock market, it is necessary to peer many years into the future to project cash flows, then discount these back – at an ever-falling discount rate – in order to discern any ‘value’. Investors buying SaaS stocks at elevated price-to-sales multiples might yet prove to be right about the future prospects for these businesses, but their margin of safety is slim.

In Asia, we have been slightly more fortunate as there are still more market inefficiencies than in most western markets.3 Nevertheless, we still come across pockets of overvaluation in certain popular sub-sectors in various countries. It sometimes seems as if the ‘growth’ investors active in these areas are speaking a completely different language to the rest of the market.

It might be tempting to short some of these stocks where overoptimism seems to be rife, but we have resisted the urge. This is fortunate, as in the last few years it would have meant a one-way ticket to the poorhouse.

Instead, we have continued our quest to invest in cash flow generative companies with respectable growth which are trading at low multiples of cash flow. This has led us down paths less trodden to markets such as Vietnam.

At the same time, we have not been averse to buying stakes in cash flow generative companies which also have investments in growth companies hiding in plain sight on their balance sheets – ‘growth in value’.

This has led to some interesting opportunities for Panah in recent years. Some of these investments have been successful; others, less so. Below we summarise a few of these experiences, along with lessons learned.

Case Study: Japanese Consultancy Firm with VC Investments (Current Market Cap US ~$75mn)

In a past Panah letter, we focused on investments in two firms which we believed to have effective capital allocation processes.4 Over time, we believed that these firms would likely be able to create value for shareholders.

One of the companies we profiled was a Vietnamese industrial conglomerate with utility investments. This company has grown to become one of Panah’s largest holdings as the market cap grew from US ~$350mn to >$1bn.

Unfortunately, however, the other stock we profiled in the same letter – a Japanese consultancy firm with numerous VC investments – has not been a successful investment for Panah. At the time of our original letter, the market cap of this company was US ~$180mn. This has since shrunk to ~$75mn today.

We believe that this experience provides a salutary warning of what can go wrong when investing in cheap companies with interesting growth investments. The story of this investment, together with the lessons we learnt from the experience, follow below.

Our original case study described a holding company with a steady cash flow generative core business (specialty ‘growth’ consulting) staffed by some of the brightest graduates from the best universities in Japan.

The surplus cash flow from this business had been deployed into a burgeoning international VC ‘incubation’ operation, as well as to large ‘private equity’ (‘PE’) stakes in businesses which management expected to grow into pillars of stable cash flow generation in their own right. These PE-style investments included a niche petcare insurance firm, a Southeast Asian marketing operation, as well as a popular event ticketing app.

The consulting company had initially been a small position in Panah for a couple of years before we accumulated more shares to make it a more meaningful holding from late 2016. At the time, the stock was trading at a substantial discount to the underlying value of its investments, while still enjoying positive cash flow from its consulting operations.

Our investment thesis was that as the company’s majority-owned petcare insurance business undertook an IPO in Q2 2018, the market would be better able to understand the value of the company’s core business and investment holdings. As a result, investors would be rewarded with a higher stock price.

We also worked closely with the management of the holding company to improve investor communications, especially in regard to disclosing the Net Asset Value (‘NAV’) breakdown of the firm’s core business and numerous investments.

The stock price ran up into the listing of the insurance business, as we had anticipated. Then, however, the company’s shares embarked on a decline – still underway – and have since lost three-quarters of their market value over the last three-and-a-half years.

What went wrong?

This was not a sell-on-the-news story for an overvalued holding company trading at an aggressive multiple of NAV. Indeed, the stock was trading below 1x NAV, and NAV has flatlined for several years rather than collapsing. Instead, this was a story of disappointment as the holding company’s core business and several investments failed to live up to expectations.

The first warning sign came as the company’s core consulting revenues and recurring profits declined sharply in FY2019/3. The company did not disclose the reasons for this disappointing development. Further investigations, however, revealed that the firm had lost its largest consulting client, a respected Japanese automotive firm which had decided to terminate all outside consultancy contracts.

This incident coincided with the implementation of a succession plan which saw the founding director of the business retire, replaced by younger managers from within the business who were promoted to senior roles.

We thought that this should have been a positive development, but were disappointed when new management were slow to address the challenge of losing the company’s largest consulting client. Instead, they seemed to be increasingly preoccupied with internal company politics.

Moreover, around the same time, unexpected developments in several of the company’s ‘incubation’ investees seem to suggest that the VC due diligence process had fallen short. Management had also been overoptimistic on the prospects for one of their PE investments, the Southeast Asian marketing operation. This had been promoted as a future cash flow ‘pillar’ of the business, but now looked more likely to be wound down.

One of the bright spots was the company’s majority stake in the ticketing app business, which continued to see strong growth. The insurance business was also gaining share and forging ahead in Japan’s underpenetrated petcare insurance market.

The problem was that the management of the consulting company and insurance firm had underestimated just how hard it would be to gain regulatory approval for the insurance firm to pay out dividends early in its life.5 This was important, as it restricted the ability of the consulting company to allocate capital efficiently between its investment holdings.6

Late 2018 saw a sharp sell-off in the stock price along with many other Japanese small- and mid-cap stocks. After a share price bounce in early 2019, we took the decision to significantly reduce the size of our holding as the challenges facing the company came more sharply into relief. We continued trimming the position in mid-2019 and early 2020, as we were unable to discern any significant operational improvements. We finally sold down our small remaining residual position as the Covid-19 pandemic struck in Q2 2021, as we judged that management would find it hard to resuscitate the consulting business in such an environment.

Although we have not closely followed the stock since divesting, it would appear that over the last eighteen months, the Covid-19 pandemic has taken a further toll on the consulting business and has also adversely affected several of the company’s VC investments. As a result, the company has recorded a net loss in the last two financial years, and the stock price has halved since mid-2019 (i.e., the time that we divested the bulk of our holding). This has in turn led to another management reshuffle.

The company currently trades at a -40% discount to the value of its stake in the successful petcare insurance company alone. In other words, investors are attributing negative value to the firm’s core consulting operations, event ticketing business and other VC investments. Even a recent large minority investment into the holding company (at a generous premium) in Q2 2021 from a major Japanese advertising firm has done nothing to stop the ongoing share price decline. A share buyback program has also failed to have a positive impact.

In most other countries, a listed company trading at such a large negative enterprise value with an open shareholder register would be a prime target for a takeover bid or a management buyout. The new owner would theoretically be able to pocket a profit just by selling the majority stake in the firm’s fast-growing insurance asset7 and other VC investments, before even considering what to do with the firm’s core consulting business. This being Japan, however, it is unclear what will happen.

Maybe investors will only give management the benefit of the doubt once they see a bounce back in the firm’s core consulting earnings? Alternatively, maybe the company is simply too small and complicated for most investors to analyse, meaning that the current situation might persist for many years? Maybe an enterprising private equity firm will eventually persuade management to conduct a buyout?

Panah made moderate financial losses during its time investing in the company and exited at an opportune moment when it became clear that the investment was not going as planned. We also spent valuable time advising the company on how to present corporate information in an effective way to investors.8 In hindsight, this time would have been better spent elsewhere.

What have we learned from this experience?

If a holding company is too small and complicated (i.e., with multiple small and/or obscure investments), few investors will take the time to understand it properly. Even if it’s possible to engage with the company’s management and persuade them to present information about the business (and its valuation) to investors in an effective manner, there are no guarantees that investors will listen if they cannot deploy a reasonable amount of capital to the investment idea.

If investors believe that management is being reticent with key information (such as the loss of a major consulting client), they will sell their shares first and ask questions later.

If the core business is not generating solid cash flow but instead starts losing money, investors will not pay much attention to the value of its investment holdings. This is probably because investors perceive that if the losses continue, the company will be a forced seller of their investment holdings, perhaps at a sub-optimal valuation. Minority financial investors (without control) are thus best to invest in a company with a solid, cash flow generative core business, where investment holdings provide additional upside but are not essential to the investment case.

It is important that investments undertaken by the company are within management’s ‘circle of competence’ (i.e., expertise which is derived from running the core business). Management should be clearly able to articulate their edge when allocating capital to other investments; if they cannot, then they probably don’t have an edge.

It also helps if the listed holding company’s investments include stakes in one or more well-known and successful companies, and even better if these companies are more famous than the holding company itself. In this era of ‘private market dominance’, it seems to matter less whether the investment holdings are listed. Indeed, it might even be preferable for the highest profile investment holding to be a successful VC-funded company which is growing fast and attracting multiple ‘up rounds’ of funding. In such case, the stock of the listed holdco might be seen as the only way for regular investors to ‘gain access’ to an investment in the successful private company, before a much-hyped IPO in several years’ time.9

If it’s not possible for a holding company to allocate capital with minimal friction between the investment holdings in its portfolio (and to new holdings), this will likely compromise the ability of the company to compound capital for investors over time.

This experience has also reinforced our prejudice that (most) management consultants would be well advised to stick to providing consulting services rather than using shareholder funds to test their investment theories in the rough and tumble of the markets.

On a positive note, we believe that the lessons from this experience have helped to strengthen our investment process. We have since tried to apply these lessons to our more recent investments. Two further examples are given below.

Case Study: Vietnamese ‘Merchant Bank’ with Fintech Investments (Current Market Cap US ~$150mn)

Fresh from our ‘defeat’ at the hands of the Japanese consulting company and its VC investments, we sought to internalise these lessons and apply them to a Vietnamese company that was introduced to us in late 2018.10

This Vietnamese company describes itself as an ‘independent investment bank’, and its scope of operations is similar to merchant banks in the west. In Vietnam, this company is also known as a brokerage firm thanks to its small stock broking business, although the company’s treasury (i.e., bond) trading and proprietary stock trading operations are larger and more significant for earnings. The company also has a niche investment banking operation and boasts a small fund management business; in recent years, these funds have consistently generated impressive returns for investors.

In general, we are not particularly optimistic about the prospects for most stockbrokers (retail or institutional). Competition is fierce and fee compression is a fact of life.11 It will probably take longer, however, for such trends to play out in developing markets.

The stock markets in Vietnam are still growing, and the firm’s brokerage operations still have room to take market share from other stockbrokers in Vietnam. The firm’s other businesses (i.e., fund management, prop trading and treasury operations) are also competitive and have room to grow.

At the time that we started to investigate the company in late 2018, perhaps the most interesting aspect of the firm’s activities was its history of seeding and building early-stage tech ventures in Vietnam. Indeed, in 2013 this merchant bank had helped to found and build what has since become the largest payments app in Vietnam, which currently has >23mn users.

At the time we first invested in January 2019, the entire market cap of the merchant bank was just US ~$35mn. A company with a market cap of this size would usually be too small for Panah to take a serious interest (as it would usually be too illiquid to establish a position or to extricate ourselves if we were wrong). In this case, however, we sensed multi-bagger potential and managed to source a small block of shares.

Taking the latest funding round valuations12 for the fast-growing payments business at the time of our investment, we estimated that the value of the merchant bank’s high single-digit percentage stake in this payments app was comfortably larger than their own ~$35mn market cap. The merchant bank itself was trading at a single-digit earnings multiple, and in effect investors were getting the merchant bank’s stake in the payments app for free.

A further funding up-round for the payments app in January 2021 has since confirmed the positive momentum of this business, giving an implied value for the merchant bank’s stake in the payments app of ~$50mn. This was still similar to the market cap of the merchant bank at the time.

Since then, the merchant bank has seen a surge in performance. Earnings from almost all segments have risen sharply, and the stock price has appreciated by ~140% year-to-date in 2021. The market cap currently stands at ~$150mn, which still puts the company on a single-digit earnings multiple. Another funding up-round for the payments app is expected before the end of this year, which should also help to underpin the value of the merchant bank as a whole.

Moreover, the merchant bank’s recent success in incubating another fintech asset management business (founded in 2017) suggests that their success with the payments app is not a one-off. This investment business also has synergies with their own operations. Although the value of this fintech asset management firm is still small in dollar-terms, the company is growing its AUM extremely quickly and is also attracting attention from various VC investors.

While we expect earnings for the merchant bank to be volatile in the coming quarters and years, we remain optimistic on the outlook for the core business as well as their fast-growing fintech investments.

Case study: Japanese e-commerce company with Southeast Asian ‘growth’ investments (market cap US ~$370mn)

We became aware of our most recent ‘stealth growth’ investment – a Japanese e-commerce company with various Southeast Asian investment holdings – in the summer of 2020 as the world started to grapple with the pandemic.

Founded in Japan in 1999 and listed in 2004 on the Mothers13 section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange, this e-commerce company has flourished over time by focusing on the niche business of selling high quality products from Japan to the rest of the world.

For some years, the company’s ‘cross-border’ e-commerce revenues were anchored by an overseas package forwarding business. This service allowed Japanese-speaking customers who lived abroad, to purchase and receive delivery of items from Japanese e-commerce websites which did not ship overseas.

This service was a hit. Over time, the company realised there was also significant unmet demand for Japanese products from non-Japanese speaking customers around the world. Japanese products have a reputation for quality and reliability, especially in Asia, yet most Japanese e-commerce websites do not support overseas payments, neither do they translate product descriptions into other languages nor offer overseas customer support.

The entrepreneurial founder of this company thus sought to build a service to fill this gap in the market. The company leverages the APIs of their Japanese e-commerce partners to retrieve and translate product information, then offers customer support across multiple languages, handles payments and currency conversion, arranges international shipping and also offers insurance. The service also allows customers to shop at multiple Japanese partner websites and combine the shipping of their purchased items into one package, thereby reducing costs.14

The online cross-border business has grown rapidly in recent years. Until last year, however, this growth was obscured by two other legacy services within the ‘e-commerce’ segment, namely ‘value cycle’ (second-hand luxury goods outlets), and ‘entertainment’ (live concerts and events).

Reporting was also confusing, which meant that investors found it hard to unravel the profit contribution from each of these sub-segments. Following engagement by Panah and other investors, disclosure improved markedly in 2020.

While the pandemic adversely impacted the value cycle and entertainment sub-segments, it also allowed the online cross-border e-commerce service to flourish. From 2020, investors were suddenly able to see how the GMV15 of the new cross-border sub-segment had been growing at a double-digit annual rate for several years, with a stable take rate16 of just under 20% and operating margins of >25% – an extremely attractive core business.

In FY2019/9, the cross-border sub-segment generated JPY 726mn in operating profit. The following year, in FY2020/9, this had grown by +132% to JPY 1,686mn. Strong growth has continued this year. During the last two years, however, the other e-commerce sub-segments (value cycle and entertainment) barely broke even.

When Panah first established a holding in this e-commerce company, the entire market capitalisation was ~JPY 35bn. This meant that the e-commerce business alone was effectively trading on a trailing mid-single digit operating earnings yield –a reasonable valuation given the growth potential for the e-commerce business. This segment, however, was not the only exciting thing that the company had to offer.

There was also significant value hiding within the ‘incubation’ segment, home to the company’s substantial investment portfolio. The company’s founder17 had made a series of savvy early-stage investments over the last fifteen years, most of which were focused on Emerging Market e-commerce firms. These had grown in value over time.

Current investment holdings include a valuable stake in what is now Indonesia’s largest e-commerce platform (expected to IPO soon), a ~5-10% stake in a leading Indian online auto marketplace (expected to IPO in 2022), and several other exciting businesses. When Panah first started researching this Japanese e-commerce company last year, the value of the investment portfolio was equal to the market cap of the entire company – classic ‘growth in value’.

The incubation segment also includes several early-stage ventures established by the company itself. We believe the most important of these to be the partnerships established with several leading e-commerce platforms in China and elsewhere in Asia (all household names).

These partnerships will eventually allow overseas customers to purchase Japanese goods directly from the online shopping platforms that are already available in their countries. While the partnerships were established recently, volumes are already starting to ramp up. As these businesses become profitable, the plan is to transfer them into the e-commerce segment. We believe that these partnerships have exciting potential and might eventually even grow to be larger than the original e-commerce business itself.

Of course, this investment is not without risks. The global pandemic has given a huge boost to e-commerce, but it is uncertain whether consumers will continue to buy online in the same volumes (especially cross-border), once retail outlets reopen and travel resumes.

We also originally worried that the Japanese e-commerce sites might eventually decide to bypass this company and sell directly to foreign consumers. Following further research, however, we believe that there is little incentive to sell directly to foreign customers at present, as the company’s transaction fee is charged to consumers rather to the e-commerce platforms. Moreover, it would require significant time and investment to develop the sort of high-quality cross-border customer support and logistics function already offered by the company.

Ramping up the partnerships with leading Asian e-commerce platforms is also challenging, as it requires cooperation with partners, country-by-country operational rollouts, as well as experimentation to see which SKUs are popular by location. We believe that the challenges experienced in building up these partnerships, however, will also serve as a significant barrier-to-entry and prevent other firms from easily replicating this business model.

The value cycle and entertainment sub-segments have been badly impacted by the pandemic, and we have questioned the ongoing relevance of these businesses. Management has a similar view and would be willing to de-emphasise these services should it not prove possible to increase synergies with other segments.18

In terms of valuation, the company has a current market cap of ~JPY 42bn and an enterprise value of ~JPY 22bn (adjusting for net cash and for the latest fair value of the investment holdings). Meanwhile, we estimate the operating businesses (excluding the sales from the incubation segment) generated operating cash flow of ~JPY 2.2bn in FY2020/9.

Bear in mind, however, that cash flow is currently being depressed by ~JPY 1.2bn in annual operating costs for the various new e-commerce ventures housed within the incubation segment, many of which are now ramping up and which we expect to break even in the coming 12-18 months. On a forward-looking basis, we estimate the company is trading on an adjusted EV-to-EBITDA multiple of ~7x for FY2022/9.19

In summary, we anticipate continued strong growth for the core cross-border e-commerce business, as well as good potential for the new partnerships with leading Asian e-commerce platforms. There is also the potential for greater synergies with the value cycle and entertainment sub-segments. Meanwhile, the company’s savvy early-stage e-commerce investments help to underpin the value of the company.

This unusual company is also becoming more confident and articulate when communicating with investors, and in the coming years we expect the stock to be rewarded with a higher multiple as management prove that they can execute on the firm’s exciting growth initiatives.

Meanwhile, upcoming IPOs for this company’s investment holdings have the potential to generate market excitement and create trading opportunities in the stock.

We believe that ‘growth in value’ investments of this sort are an interesting reflection of the inefficiencies that are on offer in Asia. Such investments also present a valuable opportunity for those investors who are willing to go the extra mile.

Thank you for reading.

Andrew Limond, Varun Dutt

The original source material has been edited for spelling, punctuation, grammar and clarity. Photographs, illustrations, diagrams and references have been updated to ensure relevance. Copies of the original quarterly letter source material are available to investors on request.

For more information on our value-oriented investment approach, see the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q3 2017 and the following Seraya Insight: ‘The Trials & Temptations of a Value Investor’.

For a review of Asian market inefficiencies, see the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q4 2019 and the following Seraya Insight: ‘Why Asia's Market Inefficiencies = Opportunities’.

For more information on the importance of capital allocation in the investment process, including these two case studies, see the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q4 2016 and the following Seraya Insight: ‘“Capital Allocators” versus “Capital Alligators”’.

The Japanese insurance regulator prefers to see early-stage insurance companies retain their earnings and build up capital buffers so as to be able to withstand future claims by policyholders.

The ability to reallocate capital between investments is a key difference between this Japanese consultancy company and our more successful investment in the Vietnamese industrial conglomerate, which over the years has been able to extract large dividends from its utility investments and redeploy these in new accretive investments, thereby compounding capital for investors.

Insurance is in general an ex-growth business in Japan. The larger Japanese insurers are thus willing to pay up for majority stakes in smaller insurance firms with dominant shares in fast-growing niches such as petcare insurance.

This lives on in the company’s investor presentations, although we’re not sure many people are paying attention given that the stock is trading at a -75% discount to the declared NAV.

The ‘private market dominance’ phenomenon might well be temporary, as a result of developments in market structure which currently favour private investment. So long as interest in VC remains at fever pitch, however, it remains relevant.

This opportunity emerged as a result of a recommendation from an experienced Vietnamese fund manager with whom we often consult – many thanks, JW.

The retail brokerage market in many countries is already seeing a trend towards consolidation among a few tech-savvy larger brokers who are offering transaction fees at or near zero. These companies will likely survive on margin fees and also payment for order flow in certain markets (a controversial yet common practice).

Supported by reputable international PE investors such as Warburg Pincus.

We are not aware of companies elsewhere in the world which focus on facilitating mass market cross-border e-commerce transactions. This may also be because the products available on Japanese e-commerce sites are sufficiently different from those available in other countries. In Japan, this company has longstanding and often exclusive relationships with many of the country’s leading e-commerce websites, so faces limited competition.

The Gross Merchandise Value (‘GMV’) is the total value of goods sold through an e-commerce platform.

The take rate is the fee charged by the e-commerce platform, thus: the take rate * GMV = revenue.

The founder eventually resigned as CEO in 2014 to focus on running an independent VC firm. He has been succeeded by an experienced management team but remains the largest individual shareholder of the e-commerce company and an important advisor to the company.

These synergies are not imaginary. For example, in the value cycle sub-segment, the company is developing an online marketplace for second-hand luxury goods sourced from Japan and selling to overseas customers. In the entertainment sub-segment, they aim to help Japanese artists and musicians sell their merchandise online and expand their followings overseas. It has been encouraging just how quickly the company has already been able to shift its ‘entertainment’ model and generate profits by taking events online.

This assumes that the new e-commerce partnerships break even within the next year (but do not make any profits) and that the EBITDA of the operating business continues to grow at ~20% per annum. Note that this also assumes the company does not divest any of its investment portfolio during the period.