'Capital Allocators' versus 'Capital Alligators' 🐊

The importance of good 'capital allocation' to drive returns, along with two relevant case studies: a Vietnamese industrial conglomerate and a Japanese consultancy firm

This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

This Insight is an extract adapted from the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q4 2016.1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Panah is always on the lookout for ‘good’ companies trading at a reasonable price. Although ‘quality’ can be a somewhat nebulous concept, most investors emphasise metrics such as high and stable return on capital and margins. We also favour firms with a solid record of shareholder value creation, and like to look at metrics such as long-term growth in book value per share (‘BVPS’) to ensure that the company has been able to compound capital over time.2

Once we have identified a ‘quality’ company which has managed to enjoy a consistently high compound growth rate, the first step is usually to understand how this has been possible.

Most ‘compounders’ which have managed to grow at a consistently high rate have been able to do so because their core business enjoys a competitive advantage (i.e., a ‘moat’) which prevents other companies coming in to compete away their high returns.3 Such firms are typically much sought-after by investors (especially when they have an easily understandable strong consumer franchise or brand), and so often trade at extremely high valuations.

While some investors are comfortable paying high multiples for good quality businesses which compound capital at high rates over the long term, our preference is to have more of a margin of safety for valuation when we invest. This is not least because it can be difficult to judge exactly how sustainable such high returns will be in the future. One always ought to consider the possibility that high BVPS growth over time might be disrupted by new technology or industry entrants.

We have also come across supposedly high-quality companies with strong BVPS growth where we think that returns will almost certainly not be sustainable. For instance, high growth over the most recent business cycle might have been driven by a combination of a strong economic upturn (driving top-line growth), a temporary (if extended) lack of competition, high operating leverage, and a fully-depreciated asset base which might well need to be replaced in the near future (at a high cost).4

In this hyper-financialised world, most markets have already been picked over by plenty of investors, and so the truth is that it is unusual to find a company with truly sustainable high returns which is also trading at a reasonable valuation. This is why it is rarely enough just to look at the headline metrics - one must also do one’s homework.

As far as we are concerned, one of the ultimate goals of long-term investment is to find a reasonably valued ‘compounder’ company which is able to continue to reinvest its cash flows at the same high rate of return.

Since inception, the Panah Fund has managed to identify only a handful of these companies trading at reasonable valuations. We remain happily invested in such stocks, even after a few have rerated to higher valuations, and we are always on the lookout for more.

Compounding through Capital Allocation

The good news is that there is another flavour of ‘compounder’ company which is also able to grow at a high and steady rate, but which seems to attract less attention from the markets. This typically means that such stocks trade at more reasonable valuations.

We are referring to companies run by good managers who have above average capital allocation skills. As a great investor once noted, a true aptitude to allocate capital well is perhaps one of the rarest abilities to be found among company managers, but probably the most important.5

Capital allocation decisions are those which determine whether and by how much the value of any company will grow over time. These decisions can be split into two broad areas: raising new capital and deploying it.

Company managers have a few ways to get their hands on new capital:

Issue stock;

Take on debt (including hybrid debt instruments); or,

Use cash flow from the business.

When it comes to deploying capital, company managers can:

Pay down debt (if any);

Pay dividends;

Buy back stock;

Invest in existing operations;

Invest in establishing a new area of operations;

Acquire other businesses;

Invest in the equity or debt of another company; or finally,

Just keep the cash in money market instruments on deposit at a bank (all too common in Japan, which is really just deferring an eventual decision!).6

Those managers who on aggregate make good decisions over time are said to be good ‘capital allocators’, and they are rare. On the other hand, we refer to the bad decision-makers as ‘capital alligators’ - they are the managers who devour investors’ capital with very little to show for it.

Capital Allocation Considerations

At this stage, a couple of theoretical examples might help to illustrate the key points.

What Happens When a Bad Manager Takes Over a Good Company?

A good ‘compounder’ company (e.g., a branded consumer goods company with strong distribution channels) is already in a fortunate position, as it is possible to generate a high level of cash flow from a relatively small capital base. Enlightened management have realised that the company’s high returns are unlikely to be matched elsewhere (i.e., no better investment alternatives), and so they decide to deploy internally-generated cash flow to expand existing operations.

In reality, capital requirements for expansion are not particularly high, and as time goes on it is not possible to utilise all internally-generated cash flow to expand operations. Management thus decides to pay out excess cash in the form of ever-increasing dividends. Investors are impressed, and are willing to pay a high valuation multiple to buy shares in the firm. Despite a high valuation, the company’s share price rises over time as earnings and dividends grow.

Everyone is happy until one day, a new CEO is appointed. He decides to pare back the dividend and instead use excess cash to acquire another firm in a different industry, paying punchy multiples for this acquisition target (despite lower returns).

Shareholders in the compounder company react by selling shares, as they anticipate that returns will deteriorate. Indeed, over time management find that they spend more energy dealing with the problem acquisition rather than focusing on the core business, and so they allow another competitor to win market share in their core business.

Challenges for the ‘Average’ Company

The ‘average’ company finds itself in a much tougher starting situation. Indeed, most firms in most sectors only generate excess returns over the cost of capital for short periods of time (and maybe not at all over the course of an economic cycle). Rather than being able to reinvest capital in a fantastic business, management must make more difficult choices about how to raise capital and deploy it.

The manager of such a business might have to think about whether to issue equity to pursue a potentially transformative but risky and expensive acquisition, or perhaps instead buy back the company’s own shares (which is perhaps a good decision if the firm trades on a low cash flow multiple).

Would it be better to gear up to increase capacity and increase industry dominance (to become the lowest-cost producer)? Or would it be better to sit on the cash and wait to acquire a distressed competitor during the next downturn? It might only become apparent many years in the future what was the ‘correct’ choice.

Capital Allocation Considerations

Capital allocation decisions might be hard, but they are important. It is possible for a CEO who runs a business in a fairly ‘ordinary’ sector (i.e., one that is not known for producing high, sustainable returns) to grow the value of the company over time by making the best capital allocation decisions possible in the circumstances.

A necessary skill seems to be the ability to balance the potential returns of the choices on offer, tempered by an appreciation for the probability-weighted outcome of such decisions. Buying back your own stock (at cheap enough multiples) is more likely to be value-accretive though is unlikely to be a game-changer, whereas gearing up to buy an expensive company operating in another industry is far riskier but has the potential to be transformational.

Another relevant consideration is whether a company’s successful capital allocation decisions are primarily driven by an extremely talented individual, or whether there is a process-driven capital allocation culture within the company that has created value over time.7

The parallels with fund management are interesting. A fund manager should be able to point to a long-term performance track-record (ideally predicated on a bona fide and replicable investment process) to demonstrate his or her capital allocation skills. In the same way, perhaps a combination of adjusted BVPS growth and share price appreciation over time should be considered the litmus test for company managers.

In any case, for fund managers and CEOs alike, we believe that the best way to keep risk at a reasonable level is to have a healthy respect for valuations. No matter whether a fund manager is buying a new holding, or if a company manager is embarking on M&A activity, building a new plant, or even buying back stock, it makes sense to pay less for the same stream of cash flow!

Case Study: Vietnamese Industrial Conglomerate (Current Market Cap US ~$350mn)

Established in 1977 as a state-owned enterprise (SOE), this industrial conglomerate now operates businesses in various sectors, including mechanical and electrical engineering services (M&E), air-conditioners, and real estate development + management. It also invests in various power and water infrastructure utility firms.

This company was among the first in Vietnam to be equitised in the early 1990s. It was also one of the first to allow foreigners to acquire shares later that decade. The chairwoman has been in her role for more than 20 years. She has driven the development of the company through a period of rapid economic growth and substantial social change in Vietnam.

From the mid-1990s, it was the household and industrial appliance (i.e., air-con) business which drove growth. 2002 was a year of change as the company established an M&E division and also built its first major office building (on a site near Ho Chi Minh’s international airport). This building was fully leased by 2005, when work began on the second office block on the same site; this was completed and leased in the following year.

By 2010, cash flows had been reinvested to develop more office buildings and a sports complex at the same location. The company made an early modest investment in a water company in the early 2000s, and then a power utility several years later, but this was apparently just part of a diversified investment strategy involving various listed and unlisted companies.

It was not until the end of the decade that the firm started to deemphasise its portfolio investments (during a difficult period for the Vietnamese economy) and started to focus on investing in utility companies.

The strategic pivot towards utilities did seem to make sense. As recently as 1995, around half the total Vietnamese population did not have access to electricity (which was generated, transmitted and distributed by State monopolies). Ambitious electrification targets had increased power access to 93% of the population by 2004, which was when the Vietnamese government formally recognised that the power sector would need to be reformed in order to meet the demands of a rapidly-growing economy.

The reforms would involve breaking the government’s monopoly on power, with a clear roadmap for power market reform starting with a move towards a competitive generation market with a single buyer of power (i.e., EVN) in the early 2010s, then a competitive wholesale market by the middle of the decade, and finally a competitive retail market in the early 2020s.

While the implementation timeline has slipped, the direction of movement is clear. The government also announced ambitious targets for a large increase in aggregate power output to 2030. To incentivise the fairly rapid addition of electricity generation capacity, there has been a recognition that Vietnam’s power tariffs (among the lowest in the region, anchored by a ~40% mix of low-cost hydropower projects) will have to rise over time.

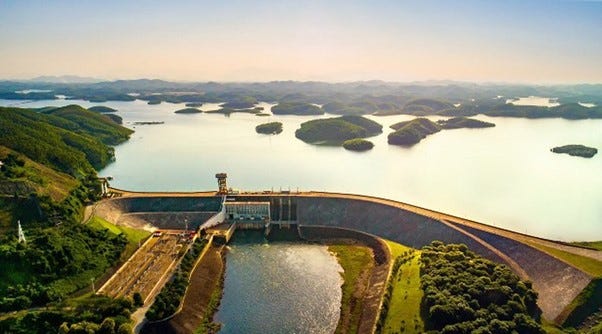

The chairwoman had started to increase the conglomerate’s investments in utilities by the end of the 2000s. One of the first major power investments was a rock-and-clay hydropower dam built during the Vietnam War era (and which is still expected to operate for a further >50 years); the company acquired a small stake at first, but it is now the majority owner of this asset.

In the intervening years, further steady investments in power plants and water treatment works have followed, with a focus on hydropower assets. The common factor among these utility investments appears to be a bias towards longer-life assets which throw off steady free cash flow, and where higher dividends can be extracted without too much trouble. These dividends are then paid back up to the holding company, to be reinvested in other areas.

In the last couple of years, most cash flow has been reallocated towards increasing stakes in existing utility holdings as well as acquiring new ones, and also developing a high-end office complex near the Central Business District of Ho Chi Minh City.

This approach to capital allocation is not rocket science, and it might well have some weaknesses. Nevertheless, the company has been careful to buy at valuations which provide a margin of safety - one recent incremental share acquisition in a power plant (admittedly in need of some upgrade capex) was transacted at an EV-to-FCF multiple of ~3.0x.8

As this conglomerate has become the de facto consolidator of Vietnamese power producers, management has found that its influence with relevant government bodies and other power companies has grown. They have also found it desirable to transfer talented employees among different portfolio companies to help encourage better operational and management practices.

Even if it is theoretically possible for a foreign minority investor to buy small stakes in listed utility companies (which might only own one plant), in practice it would be extremely difficult to replicate this conglomerate’s strategy. This is because it is effectively impossible for a foreign investor to have the same level of operational knowledge or political influence.

The company has managed to generate more than VND 1tr (~US 45mn) of net operating cash flow over the last two years, with around a third of the cash flow contributed by each main business area (i.e., [1] M&E + air-cons; [2] real estate; and [3] utility investments); the exact breakdown varies from year-to-year depending on developments in each division.

This VND >1tr in cash flow is free to be reinvested in real estate development projects or utility companies (depending on which investment opportunities meet the company’s hurdle rates), with the remainder paid out to shareholders as dividends. In practice, over the last two years the company has paid out slightly less than half this amount in dividends (implying a current dividend yield of >5%).

We first established an interest in this company in mid-2015. This grew further in the second half of 2016. At the time, the company was trading at a modest valuation (i.e., an EV-to-net OCF multiple of 5.0x).9

Despite a strong rally since that time, valuations still remain attractive in our view. The company currently sports an EV-to-net OCF multiple of ~6.5x, with anticipated growth in excess of 15% per annum.

After all, this is a company which has managed to grow adjusted BVPS at a compound rate of ~25% since 2004. We are also reassured that another well-known pan-Asian conglomerate has become the largest shareholder in this firm in recent years, and is also represented on the board.

Case Study: Japanese Consultancy Firm (Current Market Cap US ~$180mn)

Founded in 2000 by the Japan country director of a major international consulting firm and listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange in 2002, this Japanese company had a near-death experience in the wake of the Lehman Crisis of 2008.

At this point, management got religion and decided to move away from the previous strategy of levering up domestic consultancy earnings to acquire non-controlling stakes in speculative venture capital (‘VC’) opportunities. Instead, the company started to focus on how best to grow earnings from its high-return consultancy business, and then how to deploy its income to acquire meaningful stakes in businesses which over time would be able to grow into stable cash flow generators.

The consultancy division currently employs ~90 ‘business producers’ (i.e., consultants), and aims to hire the best and brightest graduates from Japan’s top universities. They specialise in giving advice to Japanese companies on growth strategies through embracing new technology, M&A, as well as participating in government-led projects (such as the ‘green city’ initiative). They also provide consulting advice to Japanese companies venturing into foreign markets through their offices in Ho Chi Minh City, Shanghai, Singapore and Mumbai.

The consultancy business generated JPY ~2.4bn of operating revenues in FY2016/310 (on assets of JPY ~1.2bn), and operating income of JPY 1.4bn; earnings have been growing at a pace of 10-15% for the last few years. The company aims to hire five new business producers each year; the largest constraint to growth is finding the right people.

In early 2011, the company acquired a majority stake in a niche petcare insurance business (the #2 operator in the sector, with the lowest loss ratio), in which they still retain a ~64% stake. Market penetration for this niche insurance sector is only 5-6%, though over time is expected to rise to ~25% in line with other developed markets.

The insurance division generated JPY ~7.9bn of operating revenues in FY2016/3 (on assets of JPY ~7.5bn). In recent years, operating profits have been depressed by large ongoing depreciation charges,11 and then last year by a large one-off increase in policy reserves. Adjusting for these charges, operating profits have increased from JPY ~175mn to JPY ~500mn over the three years to FY2016/3; this is despite substantial ongoing costs devoted to growing the business.12 Operating revenues have grown at 20-30% for the last few years, a pace which seems likely to continue.

As of end H1 FY2017/3, the company also had investment stakes in 42 additional ‘incubation’ businesses, operating in ‘growth’ areas such as digital media, environment & energy, and robotics. The value of 24 of these 42 companies had a recorded book value of JPY ~4.04bn at the end of last September, while the company’s conservative auditors have required that the 18 other investment stakes be written down to zero.

This does not mean they are worth nothing, however. Indeed, one such minority stake in a soon-to-be-listed robotics company looks set to be sold for JPY ~700mn at an upcoming IPO; this holding is effectively valued at zero on the balance sheet, and would be recorded as an investment gain when sold. Curiosities of this nature give a salient warning why book value should not be taken at face value, and why for this company, BVPS growth is a misleading metric!

The unpredictable timing of such extraordinary gains and losses – dependent on the state of the IPO market – is the reason why this company does not offer earnings guidance. Local retail investors have acquired a habit of trading the company’s stock around IPO announcements for the company’s incubation investments. This can cause substantial share price volatility, and offers the opportunity for more fundamentally-oriented investors to increase and reduce position size.

In aggregate, the company seems to have added value over time through the investments and divestments of these incubation businesses. For instance, a stake in a well-known teenage girls’ fashion show company was sold in 2015 at double the acquisition price after three years. Another ‘asset liquidation’ firm (which trades excess inventory from manufacturing firms) was sold for a slight gain after several restructuring attempts proved unsuccessful, and despite five years of losses.

That is not to say there have not been mistakes – an investment in firm distributing Japanese medical equipment in Vietnam had to be impaired in FY2016/03 (hitting company earnings) after a plunge in the share price following management problems, though to their credit they are now working to turn the firm around.

Recently-formed alliances with strong VC houses in China, India and Silicon Valley are offering interesting minority investment opportunities which are simply unavailable to most other Japanese firms. Indeed, we think that the company’s ongoing VC investment activities provide ample scope to find and build more cash flow-generative businesses.

Management believes that one of the main reasons that there are so few successful start-ups in Japan is that they do not receive enough money or support from heavily-diversified Japanese VC investors. This company, however, is not willing to just be another passive investor in its start-up incubation investments. If any investee firm shows promise and needs help, then the company is willing and able to dispatch its own employees (i.e., consultants with operational expertise in supporting start-ups) to help build these businesses.

Conversations with top management – all of whom are substantial shareholders – have revealed that they are striving to create a process to find, invest in, and build more businesses which will in the future be able to generate sustainable cash flow.

The company currently has two ‘cash flow pillars’ (i.e., the consulting and insurance businesses), and two other businesses currently have exciting potential. One is a wholly-owned Southeast Asian digital marketing and social media survey company, which was launched in 2014 and will likely reach breakeven this year (not included among the 42 incubation investments mentioned above). Another is an investment stake in an online events-ticketing company with dominant market share for ticket resales in Japan.

This consulting company is probably best described as a ‘small, growth- and cash flow-oriented consultancy conglomerate’! Unsurprisingly, there is no sell-side analyst coverage of the company, and we can find no peers with a similar business mix.

We arrive at an appropriate valuation range by looking at the company on a sum-of-the-parts basis, comparing multiples for the consultancy business and the niche insurance business to other domestic companies operating in these areas. Without going into too much detail, the value of these two main businesses appears to exceed the market capitalisation (and enterprise value) of the company by a comfortable margin. While disclosure regarding incubation investments (excluding insurance) is more limited, we still see them as interesting ‘free call options’ with the potential to make a positive contribution in the future.

The company has no debt, and cash + marketable securities currently account for ~60% of total market cap. Much of this cash is restricted, in the sense that regulations require that it be kept within the insurance business for the time being. That seems likely to change in 2017, however, as the plan is to spin off the insurance business in an IPO. A partial divestment of this attractive business would free up cash for new investments and would also hopefully allow the insurance business to pay dividends in the future. This insurance IPO might also provide a catalyst for the share price of its parent company, as it will become much easier for investors to value the company on a sum-of-the-parts basis.

In private, management admit that they are inspired by the Berkshire Hathaway approach to capital allocation, while they also have an infectious enthusiasm for the growth potential of the new businesses in which they invest.

We have substantial confidence in their approach. Our only recommendation to date has been to recommend that the company considers hiring investment professionals as it grows, to help implement the investment process and assist on due diligence. Management appears to agree, but as always, the challenge is to find the right people.

Thank you for reading.

Andrew Limond

The original source material has been edited for spelling, punctuation, grammar and clarity. Photographs, illustrations, diagrams and references have been updated to ensure relevance. Copies of the original quarterly letter source material are available to investors on request.

It is necessary to make various adjustments to BVPS (e.g., to account for capital reductions). Depending on the company in question, there are also clearly drawbacks to being too reliant on metrics such as BVPS, as inaccuracies can creep in for various reasons, for instance: property, plant and equipment are recorded at cost minus accumulated depreciation, but depreciation rates might be inappropriate and carrying values can underestimate the replacement cost of such assets; real estate and securities are recorded at cost in many accounting jurisdictions, which can be much lower than market value; the value of intangible assets (especially goodwill) can be overstated in the accounts; jumps in BVPS as a result of one-off asset injections and/or trading gains, etc. It is always possible to make adjustments on a company-by-company basis.

Typical examples of competitive advantages are: product differentiation (e.g., brand); strong distribution channels; high switching costs (i.e., customer loyalty); high capital requirements; technological edge (e.g., patents and IP); economies-of-scale (e.g., lowest-cost producer, network effect); government regulation and policy (including tax benefits); other specific advantages (e.g., access to materials, unique location), etc.

We have come across some companies in fairly ‘ordinary’ sectors such as low-end detergents, plastic pipes and cardboard boxes, that have managed to sustain high returns on invested capital of >25% for most of the last decade, and churn out strong BVPS growth of >30% for the last five years. We do not have strong conviction, however, that such returns and compounded profit growth will be sustainable. We can envisage various challenges which might emerge, such as higher materials prices, more stringent environmental standards, more intense competition, or expensive capacity expansion needs. (Indeed, previously high returns and impressive BVPS growth for many Chinese low-end manufacturing companies proved unsustainable post-2011.)

“After ten years on the job, a CEO whose company annually retains earnings equal to 10% of net worth will have been responsible for the deployment of more than 60% of all the capital at work in the business.” (1987 Berkshire Hathaway letter to shareholders). For those with further interest on Mr Buffett’s views on capital allocation, his 1994 Berkshire Hathaway letter to shareholders and AGM comments might also be of interest.

This summary is drawn from the book ‘The Outsiders: Eight Unconventional CEOs and Their Radically Rational Blueprint for Success’ by William Thorndike, which also includes eight interesting case-studies of companies lead by managers with notable capital allocation skills.

The classic example of the effective maverick allocator is Henry Singleton of Teledyne.

Enterprise Value to Free Cash Flow ratio - the lower the multiple, the ‘cheaper’ the company.

Enterprise Value to Net Operating Cash Flow (i.e., cash flow after maintenance capex) - the lower the multiple, the ‘cheaper’ the company.

The fiscal year ending March 2016.

For depreciation of deferred assets, a peculiar requirement of Article 113 of the Japanese Insurance Business Law which states that set-up costs must be amortised over ten years; these have now been fully amortised. The same law allows deferral of business expenses for the first five years after establishing an insurance business.