Two 'Special Sits': Vietnamese Convertible Bonds and Sri Lankan Local Government Debt

Investing in some difficult-to-define ‘special sit’ opportunities: Vietnamese ‘busted’ convertible bonds and Sri Lankan local currency debt

This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

This Insight is an extract adapted from the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q2 2023.1

In past letters, we have endeavoured to bring our investment process to life by explaining the different investment strategies which we pursue, as well as describing concrete examples of our investments – both successful and unsuccessful.

In past letters, we have covered some of our ‘compounder’ investments,2 ‘deep value’ investments,3 ‘capital cycle’ investments,4 as well as single stock shorts.5 One area we have not written much about so far, however is the fund’s idiosyncratic ‘special situation’ investments.6

The fund’s ‘special sit’ positions are opportunistic investments which are by nature difficult to categorise. They usually consist of unusual situations where we believe there is a good chance to earn outsized returns in the near term.

In general, our special sit investments tend to be off-the-radar for most other investors, involve taking advantage of market inefficiencies, and generate a return stream which tends not to be correlated to the regional equity markets.

Panah is currently invested in two special sit opportunities, described in more detail below.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

‘Special Sit’ Case Study: Vietnamese Convertible Bonds

Panah first initiated this special sit investment position in September 2022. We then added to the position in late Q2 2023. This position consists of holdings in two ‘busted’ convertible bonds (‘CBs’) issued by companies controlled by Vietnam’s largest conglomerate.

This conglomerate is active in sectors such as real estate development (residential and commercial), healthcare, education, as well as electric vehicle assembly and distribution. It is one of the top ten private companies in the country, with revenues in excess of 1% of Vietnam’s GDP.

In recent years, the conglomerate has overextended itself as a result of a reckless expansion into electric vehicles. As a result, the group is burning cash and has substantial debt obligations coming due in the next two years.

Two US Dollar-denominated CBs, issued in 2021 with a maturity of five years, have put options which come due in April and September 2024. In other words, if the CBs are trading below the put price on the relevant dates in 2024, the holders of the CBs are able to demand that the company buy back the CBs at a premium to par.

Currently, the CBs are trading at a substantial discount to par, with implied yields-to-put just below 30%. This valuation implies that investors believe that the company will not be able to pay off these obligations when these put options come due.

Having performed a ‘burndown’ analysis of the company’s assets and liabilities, and discussed the company’s choices with management, however, we believe that the company is both willing and able to make good on these obligations. They are aware that if they do not, they would be shut out of international funding markets for the foreseeable future, thereby stymying their ambitious plans for the electric vehicle division.7

That does not mean, however, that the company does not have some hard decisions to make. In the absence of a massive reduction in cash burn or a substantial equity raise, the firm will likely have to monetise some of the relatively high-quality real estate assets (residential and commercial) which are held within its subsidiary companies. Indeed, this process has already begun.

Given that cash is extremely tight within the group at this time, it is unlikely that the parent company will be willing to see money ‘leak’ from any group companies to other shareholders. Cash dividends are thus probably off the menu for now. Moreover, the rules governing transactions between group companies are complex, and management does not have a reputation for pristine corporate governance.

As a result, our strong preference at present would be to avoid being a minority shareholder of any group company. We are happy, however, to be compensated with very high US Dollar yields for owning the CBs. These also sit higher in the capital structure than equity, ranking alongside other senior unsecured creditors.

If this is such a good investment opportunity, then why does it exist?

Vietnam is not an active market for CBs, and the international CB investment community is not particularly familiar or comfortable with the economic and political situation in Vietnam.

Last year’s anti-corruption campaign in Vietnam scared away many potential international investors. This was especially because it came on the back of a similar severe crackdown in China from 2021 which resulted in bond defaults and severe distress in the Chinese real estate sector.8 Such events thus appear to have prompted international investors to dump this Vietnamese conglomerate’s CBs, depressing valuations.

On the other hand, most domestic investors in Vietnam are either unfamiliar with investing in convertible bonds (as they focus on either equities or debt) or are unable to do so as they are not set up to transact on the international markets where these CBs trade.

Note that yields on the conglomerate’s domestic bonds with a similar tenor (which are more freely bought and sold by local investors) are currently trading with yields as low as 9-10%! We would expect the CBs to trade at broadly similar valuations, yet they trade at a massive discount.

In summary, we believe that market inefficiencies have created the opportunity to invest in these ‘orphaned’ CBs. There would appear to be few ‘natural investors’ who are able to come in and bid up prices. In the absence of specific news flow on asset divestments or equity issuance from the conglomerate, prices have remained depressed.

We cautiously note that the worst appears to be over for the real estate sector in Vietnam, with regulatory approvals starting to grind into gear, and construction and sales on various projects recommencing. Interest rates have also fallen, once again making mortgages accessible for Vietnamese consumers. This is good news for the conglomerate, which should now be able to start generating higher cash flows from its residential real estate arm.

We have also identified a low-cost hedge which, although it does not provide a perfect offset, should nevertheless protect our downside in most negative scenarios. As for ‘blue sky’ potential, while owning CBs would usually give investors the potential for additional upside (should the stock price rally beyond the conversion price), we think such an outcome unlikely in this case.

Regardless of this, we are happy with a US Dollar yield-to-put in the high-20% range for this special sit opportunity. We suspect that when the rerating comes, it will likely be sudden.

‘Special Sit’ Case Study: Sri Lankan Local Currency Debt

Sri Lanka has suffered significant hardship in recent years. Last year, the country experienced its worst economic crisis since independence in 1948, along with severe social and political turmoil.9

The current run of trouble started with the tragic Easter bombings of April 2019. Worries over national security in the wake of the attacks contributed to the reelection of the Rajapaksa dynasty later that year.

This set the stage for a series of poor policy decisions, including tax cuts, debt monetisation, and a ban on chemical fertilisers which crushed the country’s important agricultural sector. The blow to tourism from the Easter bombings was then further compounded by the Covid-19 pandemic, which denied the country an important source of foreign currency income.

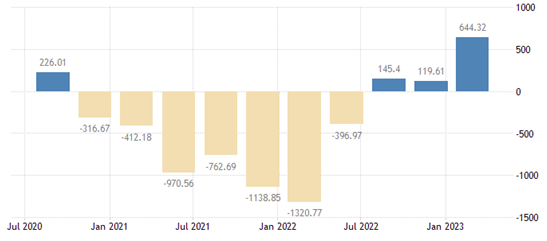

Very soon, the government found itself with little in the way of tax revenues or foreign income. From mid-2020, the central bank was also pressured to burn forex reserves to defend the currency at an unsustainable level.10

With forex reserves all but exhausted, the currency went into freefall, depreciating by a massive -45% over the course of two months from March 2022. Sri Lanka had little choice but to halt all external debt payments, and by May 2022 the country had defaulted on its external debt for the first time in its history.

The exhaustion of forex reserves and collapse of the currency catalysed a massive political and social crisis. Sri Lanka quickly found itself without enough hard currency to pay for food, fuel or medicine. This led to widespread power cuts, dramatic scenes of citizens queuing for meagre fuel rations (Figure 3.1), as well as increasingly violent protests against the government (Figure 3.2).

Protesters even managed to occupy the presidential palace. They then entered the prime minister’s private residence, setting it alight along with houses belonging to 38 other politicians. These protests forced the most prominent members of the Rajapaksa family, the prime minister and the president, to flee and resign their posts amid a state of emergency.

The economic crisis and the protests also catalysed the appointment of a new, independent central bank governor in April 2022. He immediately hiked rates from 7.5% to 14.5% in order to tame inflation and defend the currency.

Veteran politician Ranil Wickremesinghe was then elevated to the presidency in July 2022 and tasked with finding an end to the turmoil. Given the severity of the crisis, he was able to push through unpopular measures that would have been unthinkable even as recently as several months before.

The new president also immediately commenced negotiations with the IMF. He quickly set about implementing the measures required to unlock funding, including spending cuts, large tax increases and power tariff hikes. This also required agreement from major bilateral creditors, China and India.

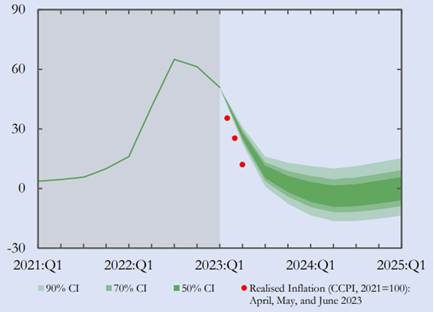

The crisis, along with these restrictive measures, took a massive toll on the economy as GDP contracted by -7.8% in 2022. As the crisis unfolded, Sri Lankan CPI spiked to as high as ~74% yoy in September 2022, driven by currency depreciation and global inflationary pressures (Figure 4).

Sri Lankan government bonds sold off hard, with 10-year yields peaking in the low-30% range in Q4 2022. The central bank had already raised interest rates to the mid-teens in early 2022 to defend the currency; it then continued to raise rates to a peak of 16.5% in March 2023.

When I arrived in Colombo in early February 2023 – my first trip to the country in several years – I found that a semblance of normality had already returned to the city. This relative stability was in contrast to the somewhat alarmist ongoing international media coverage.

While import restrictions on many goods still remained, food and fuel were more readily available. As always with crises of this sort, the poorest members of society continued to suffer. However, there were no more queues at gas stations, power cuts were rare, and medicine imports were increasing.

Holidaymakers had started to return to the country, although tourist numbers were still lower than pre-2019 levels. While there were still sporadic protests against the government – mostly by middle class and government employees who were outraged at the cost-of-living shock from higher tax rates and high inflation – these demonstrations were mostly non-violent.

Meetings with the central bank and senior executives from several major local companies indicated a high degree of realism, resilience, and willingness to make sacrifices among policymakers and corporates. Our meetings also seemed to indicate the tantalising possibility of a relatively rapid path to macroeconomic stabilisation for the island nation.

The IMF executive board was set to approve a US ~$3bn bailout for Sri Lanka in March 2023. The current account balance had already moved into surplus by Q3 2022, providing some support for the currency (Figure 5).

Taking into account base effects and falling global inflationary pressure, it seemed likely that CPI would fall into the single-digits by mid-year – a rapid reversal (Figure 4). If inflation were to fall to such an extent, this would also make it more likely that the central bank would be able to cut interest rates more aggressively, thereby alleviating some pressure on the economy.

Some brave frontier market equity investors saw this as a good moment to start topping up their holdings in the depressed domestic equity market. We also considered buying equities, but still had concerns about various issues.

These included very poor liquidity in Sri Lankan stocks; substantial ongoing pressure on the consumer and corporate earnings from higher tax rates, interest rates, power tariffs and other costs; a high level of NPLs in the banking system; the risks to growth and political stability from agricultural issues (including a failed monsoon); and the potential for a delay in the proposed IMF bailout (e.g., if major bilateral debtor China were to act as a ‘spoiler’, or if domestic political challenges were to emerge given the country’s ongoing structural issues).

In the medium- to long-term, there remains substantial doubt as to whether Sri Lanka will be able to stick to the new IMF plan, which requires far-reaching structural reforms and sacrifices from the entire population. After all, this is the seventeeth time that Sri Lanka has sought an IMF financing program. Even if the crisis has been bad enough to force through some serious reforms, scepticism is still warranted. The first major hurdle will likely be the next presidential election, which must be held before November 2024.

Even if we did not have strong conviction in the immediate investment case for equities, however, we did have more certainty that the Sri Lankan Rupee should enjoy more stability in the near-term.

After all, the current account balance had already moved into surplus, with a delayed tourism recovery in 2023 set to boost dollar earnings further (Figures 6.1-6.2). The country was also reported to have generated a primary budget surplus for the first five months of 2023, comfortably ahead of IMF expectations. Remittances also seemed set to climb sharply, not least because so many Sri Lankans had left the country during the crisis. The Rupee appreciated sharply in early March, from ~360 against the US Dollar to ~320, as the IMF started to disburse its first tranche of funds.

As stability returned in 2023, Sri Lankan government securities also started to rally, with yields on both 12-month T-bills and 10-year bonds falling from >30% in late 2022 to ~25% by end-March. This was despite significant uncertainty at the time surrounding the exact nature of the debt restructuring that would have to be agreed with the IMF by September – the only thing that seemed certain was that most government debt (domestic and external) would be subject to some sort of haircut.

Rather than immediately taking on uncertain and illiquid equity risk, we thought that ~25% local currency yield in a more stable Rupee seemed like an attractive prospect. To mitigate the risk of losing from the debt restructuring, we identified the one area of government debt which seemed unlikely to be subject to any haircut for ‘regular’ investors, namely local currency T-bills.

We had high conviction that these would remain untouched, as the government had discontinued bond issuance and was relying on T-bills to finance the day-to-day running of the country. The central bank governor confirmed our suspicions in late March when he announced that “Treasury bills would not be treated”.11

Rather than setting up accounts to buy T-bills directly, we opted for a relatively quicker and easier route: investing in a Sri Lankan money market fund run by impressive investment professionals at a well-established local asset management company. After setting up the relevant trading and bank accounts (and performing ‘roundtrips’ to test the subscription and redemption process), we began to deploy more funds to this trade in early May. At that time, the yield on offer was ~23%, and the fund had an average duration of around seven months.12

Sri Lanka’s progress so far in 2023 has been remarkable. Inflation has fallen from close to 60% yoy at end-2022 to 12% at end-June, with further declines expected in coming months. This has enabled the central bank to cut rates twice (in early June and early July), from a high of 16.5% to 12% for the reverse repo rate, with further rate cuts expected. This should help to reduce the burden on indebted corporates and households, supporting growth.

There are also high hopes for a rebound in tourism during the high season later this year (Figures 6.1-6.2). If any readers of this letter had been thinking about visiting Sri Lanka, we encourage you to do so soon and support the country on its path to recovery!

Even as the local currency has strengthened (to a recent high of 290/US$, and is now stable around 320/US$), the central bank has also succeeded in building its forex reserves at a faster than expected pace, to US ~$3.5bn. This provides a valuable buffer and will allow the central bank to intervene in case of any future ‘excessive’ currency volatility.

A follow-on trip to Sri Lanka in mid-June gave us the opportunity to meet several senior central bank officials and senior management from various blue-chip companies. Despite all the difficulties that the country has been facing, we were pleasantly surprised by the general confidence and determination that Sri Lanka is on the path to recovery.

On 1 July, the government approved a domestic debt optimisation (‘DDO’) plan. This provides more clarity as to the expected treatment for holders of various forms of government debt and is a key prerequisite to pass the IMF’s first review (scheduled for September).

On the back of this DDO plan, Sri Lankan government securities have rallied strongly: T-Bills with a six-month maturity currently yield ~16%, and bonds with a maturity greater than 24 months yield below 15%.

The money market fund in which Panah is invested has a duration of 5-6 months and still yields in the low-20% range. As the fund’s T-Bill investments start to mature in August and September, we expect the yield of the fund to drift lower (given that reinvestment into new securities will be at lower yields).

We are happy to run our investment in the money market fund for now, perhaps augmenting this investment by switching some of this holding into a fund which holds longer-duration bonds. These bonds are still yielding in the mid-teens, and we would expect them to make additional capital gains as inflation and interest rates continue to fall.

In the coming months, we expect various positive catalysts in the form of more interest rate cuts, parliamentary approval of the central bank independence bill, the first IMF review (scheduled for September), as well as more clarity as to the trajectory of the economy. In the medium- to long-term, we perceive more uncertainties.

Note that Sri Lanka’s geographical location in the Indian Ocean, off the southeast coast of India and close to multiple sea lanes, makes the country a place of vital geopolitical interest. China, India and the US have been competing for influence, and this has only intensified since the crisis.

The Rajapaksas were perceived to have been close to China (supporting various One Belt One Road projects), but it was India which stepped up during the worst moments of the turmoil to provide critical aid for Sri Lanka. This came in the form of more than US $4bn in credit lines, currency support, fuel and medicine, as well as essential support at the IMF.

Now, all three countries are competing to invest in infrastructure and development projects in Sri Lanka (including energy and ports). This makes it more likely that the country will attract higher levels of foreign investment in the coming years, which should help to support growth. Investors will need to balance positive tailwinds of this sort against other risks of the sort mentioned earlier.

Depending on Sri Lanka’s progress over the rest of the year, we have various choices. We might continue to hold our fund investments, we might choose to sell our holdings in the fund and repatriate our funds, or instead we might decide to reallocate into the Sri Lankan bond market or even make equity investments.

Any major decisions can probably wait until we make another research visit to Sri Lanka later this summer. For now, though, we are happy to report that our ‘special sit’ trade in Sri Lanka appears to be on the right track.

Thank you for reading.

Andrew Limond

The original source material has been edited for spelling, punctuation, grammar and clarity. Photographs, illustrations, diagrams and references have been updated to ensure relevance. Copies of the original quarterly letter source material are available to investors on request.

For more information on ‘compounder’ investments, see the Panah Fund letters to investors for Q3 2018 (pp.4-9) and Q4 2020 (pp.7-10), as well as the following Seraya Insights: ‘“Compounders”: The Ultimate 'Lazy' Investment Choice?’ and ‘Case Study of a Testing “Compounder”’.

For more information on ‘deep value’ investments, see the Panah Fund letters to investors for Q2 2018 (pp.6-8) and Q3 2021 (pp.3-11), as well as the following Seraya Insights: ‘Shareholder Engagement & Activism in Asia’ and ‘“Growth in Value”: Investing in Value Stocks with 'Hidden' Growth Assets’.

For more information on ‘capital cycle’ investments, see the Panah Fund letters to investors for Q4 2018 (pp.8-12) and Q1 2019 (pp.4-12), as well as the following Seraya Insights: ‘“Capital Cycle” Investing: The Market-Cycle Diaries’ and ‘Anticipating the End of the Downcycle in a Radioactive Sector’.

For more information on single stock shorts, see the Panah Fund letters to investors for Q4 2015 (pp.2-5), and the following Seraya Insight: ‘Single-Stock Shorts: A Focus on Aggressive Accounting’.

Our only previous ‘special sit’ case study (a Thai turnaround story) can be found in the Panah Fund Q3 2015 letter to investors for Q3 2015 and the following Seraya Insight: ‘Two Case Studies: a Japanese 'Deep Value' Investment & a Thai 'Special Sit' Turnaround Opportunity’.

The CBs are traded internationally, and not on domestic markets. (They are listed on the SGX, with Euroclear and Clearstream Lux as clearing houses.) Any failure to honour these CB obligations would likely mean that the company would be shut out of international funding markets for some time.

There have been major differences between the rolling crackdowns in China and the anti-corruption movement in Vietnam over the last 18 months. For more details, see the Panah letter to investors for Q1 2023 and the following Seraya Insight: ‘Vietnam: Disappointments and Opportunities’.

Many thanks to Marianne Page, Bimanee Meepagala and Kuhan Vinayagasundaram for their patient explanations of the complex situation in Sri Lanka, as well as their helpful comments when composing this note.

By this time, Sri Lanka had little in forex reserves other than a Chinese swap line worth US $1.5bn extended in May 2021, which was in any case not useable due to certain preconditions.

That is, all T-bills except for those owned by the central bank, which would be subject to ‘treatment’.