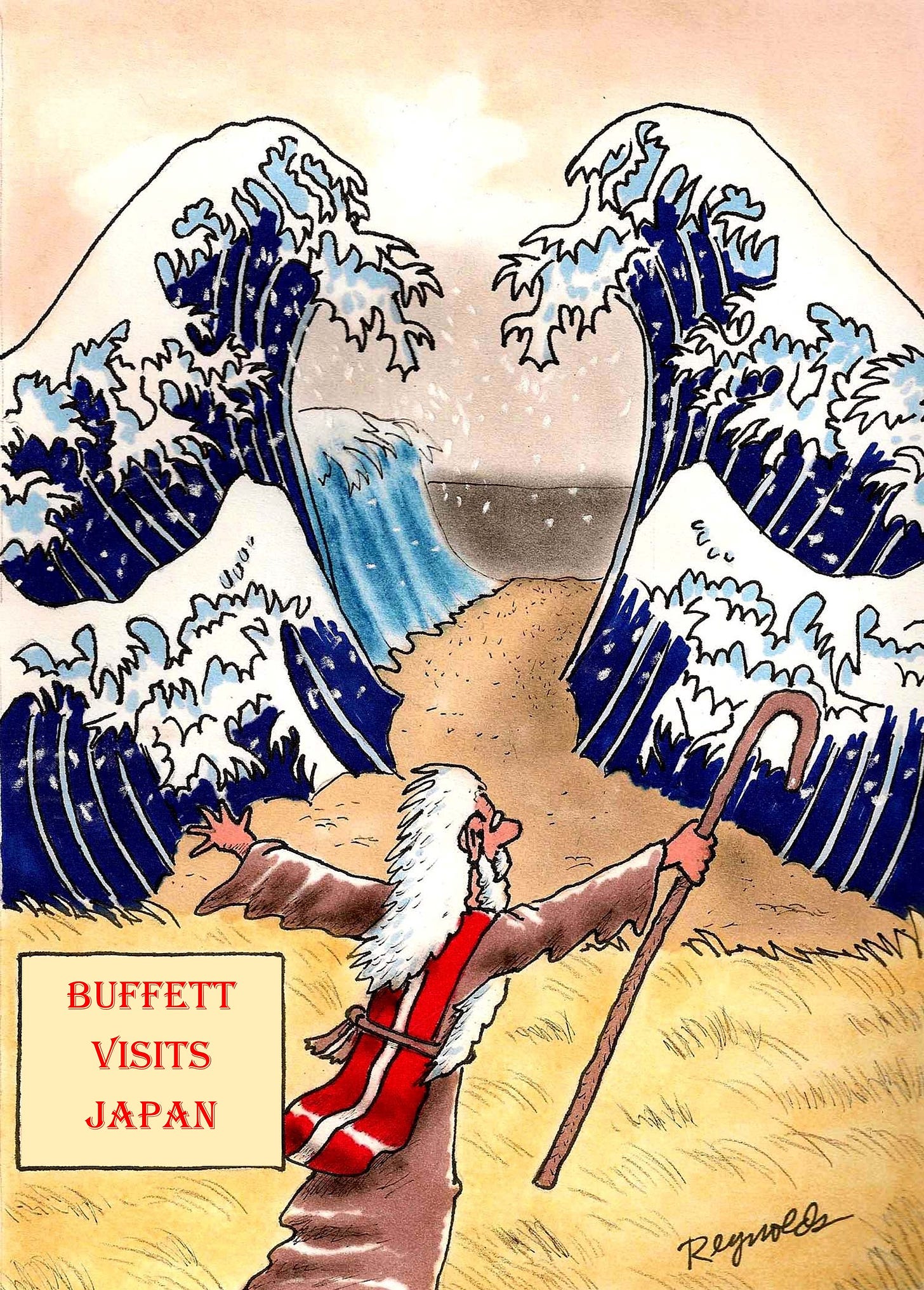

Japan: Warren Buffett Takes the Plunge & Yoshihide Suga Take the Reins

Why Warren Buffett is finally buying Japanese stocks, and the potential for structural reform in Japan under a new prime minister

This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

This Insight is an extract adapted from the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q3 2020.1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Warren Buffett Takes the Plunge

In March 2013, shortly before the Panah Fund was born, the Nikkei Veritas published an article entitled: ‘Which Japanese stocks would Buffett buy now?’.2 The journalists screened for stocks with: a market capitalisation of JPY >50bn; positive cash flow and operating profit for the last five years; an RoE of >10%; a PBR of <2.0x; and a net debt/equity ratio of <100%.

At the time, only 15 stocks met these criteria. These companies included various niche manufacturers: power drill maker Makita, dental equipment specialist Nakanishi, writing instrument company Pilot, and industrial conglomerate Hitachi. The list also mentioned various domestic retailers: Hokkaido-based supermarket chain Arcs, drugstore operator Create SD, Chinese restaurant chain owner Ohsho Food Service, and work clothes retailer Workman.

Seven-and-a-half years later, in August 2020, Mr Buffett finally took the plunge and announced that over the previous 12 months, a subsidiary of Berkshire Hathaway had started to buy its first ever Japanese stock holdings.

The US ~$6.5bn investment comprises a 5% passive position in each of Japan’s five major trading houses: Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Sumitomo, Marubeni and Itochu. He added that in the future, Berkshire might increase each stake to 9.9%.

None of Mr Buffett’s 2020 stock picks were included in the Nikkei list from 2013. Indeed, none of the stocks purchased by Berkshire Hathaway even came close to meeting the Nikkei’s 2013 criteria (then or now). The investments also seemed to violate Mr Buffett’s time-honoured precepts to invest only in ‘easy to understand’ companies which have effective ‘barriers-to-entry’ that are able to resist intense competitive pressure.

The Japanese trading companies date from the pre-war era, and head up corporate groups which encompass a veritable cat’s cradle of interlocking shareholdings. During Japan’s post-war rise, the sogo shosha served as commodity procurement houses to feed the country’s voracious appetite for energy and materials. More recently, they have expanded downstream into retail and other unrelated business lines.

Needless to say, Mr Buffett’s latest Japanese investments have thus caused much head-scratching among western observers. Was it simply that Berkshire’s US ~$140bn cash hoard was burning a hole in his pocket?

We see cunning amid the confusion. Although some see the Japanese trading houses as old-fashioned conglomerates, we agree with their description as “conservative, old economy PE funds”. They trade at low valuations (with all of them except Itochu on a price-to-book ratio of <1.0x). They are staffed with talented individuals from the best universities in Japan. They also have extensive networks which span the globe. Mr Buffett also clearly sees the trading companies as valuable future sources of deal flow,3 and the five companies will no doubt compete to present to Berkshire the best co-investment opportunities that they can find.

Over the last year, Berkshire Hathaway has taken advantage of its stature and favourable credit rating to raise US ~$6bn in Yen-denominated bonds with an average coupon below 0.6%. This effectively hedges the firm’s Yen exposure. By investing in a basket of cheap Japanese trading companies, Berkshire is also collecting an average 12-month trailing yield of >4%, which more than covers the interest expense on these bonds. Mr Buffett is thus deploying a minimal amount of equity capital while also enjoying positive carry on his investment.

In our view, however, the most important point is that by buying stakes in the resource-heavy Japanese trading houses, Mr Buffett is investing in a cheap inflation hedge. The sogo shosha might not meet the legendary investor’s acclaimed quality criteria, but then he has often broken his own ‘investment rules’ in the past.

This decision is also in character with other recent Berkshire investment decisions, including the recent US ~$10bn purchase of a gas pipeline network from Dominion Energy, and a small (~$564mn) stake in gold- and copper-miner Barrick Gold. Perhaps it is time for investors to dust off Buffett’s articles from the 1970s, when he wrote about the risk that inflation poses to equities.

On another note, we see Berkshire’s decision to buy the trading houses as an endorsement of the ‘investability’ of Japanese stocks. Regardless of the massive exit of foreign capital over the last five years, Japan is a cheap and inefficient market (especially compared to the US). We fully expect that more foreign investors will see fit to deploy capital to Japan in the coming years.

Japan’s New Prime Minister Embraces Reform

Mr Buffett famously hails from a small city in the rural Corn Belt of the US. Mr Yoshihide Suga, the new prime minister of Japan, comes from a family of strawberry farmers in Japan’s northern snow country. He took power in mid-September after the surprise resignation of former prime minister Abe for health reasons.

Mr Suga previously served as Chief Cabinet Secretary and was known as the eminence grise of the Abe administration. His origins and instincts appear markedly different to those of the other blueblooded politicians who have sat atop the mighty edifice of the Liberal Democratic Party (‘LDP’) of Japan.

Whereas Mr Suga prefers to project an austere rather than an avuncular image, Mr Buffett would no doubt approve of Mr Suga’s economic inclinations, which are said to favour deregulation and structural reform.4 This is welcome, as in recent years, the ‘third arrow’ of Abenomics – reform and revitalisation – has misfired.5

One of Mr Suga’s first decisions was to put pressure on Japan’s oligopolistic telecom firms by announcing that phone bills are too high and should be cut, a move which is likely to be popular with voters. A few weeks later came the shock disclosure that telecom behemoth NTT, partly owned by the Japanese government, would buy out the remaining public float in its mobile telecom subsidiary NTT Docomo at a generous ~30% premium. This reportedly came after close consultation between Mr Suga and the senior management of NTT.

Another of Mr Suga’s key policies is the consolidation of Japan’s numerous moribund regional banks. One likely beneficiary of this move is a diversified financial services firm which has recently purchased minority stakes in several of Japan’s stronger local banks.

This firm provides these affiliate banks with operational and risk software, and also gives them access to investment products, thereby ‘picking the winners’ (or at least the survivors) among the regional banks. In the future, such an alliance or combination of regional banks might have the potential to compete as a new ‘megabank’. We expect more news from late November as Japan’s antitrust rules for regional companies (including banks) are set to be eased.

At the heart of Mr Suga’s proposed reforms is the recognition that despite Japan’s much lauded technological excellence, especially in manufacturing, the country is running far behind the rest of the developed world when it comes to the efficient use of Information Technology.

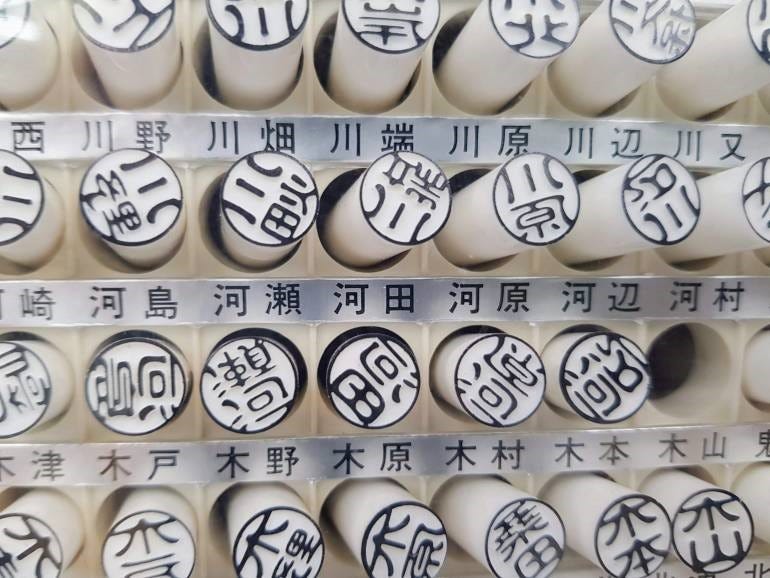

Anyone who has spent time in Japan can recount numerous anecdotes about the still widespread use of inefficient fax machines and hanko stamps for documents. Indeed, Mr Suga’s new Administrative & Regulatory Reform minister, Taro Kono, would like to replace these antiquated technologies with a more efficient, online approach to government services. A digital agency is due to be established in 2021 with input from the private sector.

Japan’s larger problem, however, may well be in the corporate sector. Many Japanese companies have a habit of maintaining expensive, inefficient legacy IT systems6 which are not fit for purpose and often have glaring security vulnerabilities. A recent example is the recent full-day trading shutdown of the Tokyo Stock Exchange owing to a technical glitch, which is attracting widespread media scrutiny and criticism. The Mitsubishi Electric breach, involving the theft of sensitive government data, is one of a series of recent defence-related hacks.

Japan’s IT deficiency has already been recognised as a serious problem by the top levels of the Japanese bureaucracy. In September 2018, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (‘METI’) released a comprehensive and uncharacteristically blunt report which warned that the economy is facing a ‘2025 Digital Cliff’, when economic losses from maintaining outdated IT systems will snowball to JPY 12tn per annum (three times the current level). The solution they proposed was that business owners should embrace ‘Digital Transformation’ (‘DX’) to boost growth and enhance competitiveness.

Mr Suga now appears keen to take concrete action to encourage change. It seems likely that Japan’s FY2021 budget will include incentives, including tax breaks, to encourage private companies to adopt DX. We also see a strong possibility that the upcoming NTT consolidation is a prelude to creating a digital champion to drive adoption of 5G and IoT technologies.

Foreign investors in Japan have long bemoaned the country’s low productivity, which has supposedly caused several ‘lost decades’ of growth. The solution embraced by former prime minister Mr Abe was extreme monetary easing from the Bank of Japan, albeit tempered by fiscal consolidation from the Ministry of Finance (involving two consumption tax hikes in the last four years). Despite tax cuts and other piecemeal changes, Mr Abe made few transformative structural reforms during his record long tenure as leader of the country.

Perhaps this was because Mr Abe’s main concern was not growth. Instead, he saw a strong economy as a means to attain his ultimate goal, which was to change Japan’s pacifist post-war Constitution. This policy lacked popular support in Japan (although public opinion may change sooner rather than later if China continues on its current aggressive foreign policy trajectory).

Mr Suga, on the other hand, appears to be focused on economic strength for its own sake. Rather than relying on monetary policy to do all the heavy lifting, the initial signs are that he understands the need for supply side reform. There will undoubtedly be strong resistance from vested interests. Nevertheless, if Mr Suga can maintain support within the LDP, he stands a chance of effecting the real change that has been elusive for so long. We watch with interest.

The one politically sensitive area which is in most dire need of reform is of course the labour market. Japan has a bifurcated jobs market which rewards seniority over ability for full-time employees. This has created an army of informal short-term, younger workers who do not enjoy the same employment protection or rewards as the older generation.

The jobs market tightened during Mr Abe’s tenure, mostly thanks to changing demographics as baby boomers retired. Encouragingly, this also boosted the female labour market participation rate to record levels, high above the OECD average. This phenomenon also meant, however, that Mr Abe was largely able to avoid the prickly problem of labour market reform.

Unsurprisingly, Mr Suga has so far been silent on this tricky topic. As the pandemic impacts employment around the world and at home, however, it will not be easy to avoid the issue of Japan’s jobs market. Given changing work patterns during the pandemic (such as a record number of Japanese working from home – unthinkable in the past), this might yet be an area which is ripe for reform. Any indication that Mr Suga is willing to tackle this difficult matter should be viewed in a positive light.

More generally, we think the new commitment to reform might well encourage foreign investors to give Japanese stocks another look. Japan is a cheap market, especially compared to the US (and China). As we have noted on numerous occasions, Japan is also a relatively inefficient market, with limited analyst coverage and investor involvement.7

Just like elsewhere in the world, certain Japanese ‘theme stocks’ have performed very well in recent years and are already trading at elevated valuations. Examples include companies involved in digitalisation and SaaS (e.g., online medical portal M3, and cloud accounting software providers Freee KK and Money Forward).

In Japan, however, there is also a critical mass of relatively unknown companies trading at cheap valuations which are likely to be beneficiaries of increased digitalisation. Such established firms typically already operate cash flow generative businesses, but also have ‘hidden assets’ in the form of new economy ventures which are in the process of emerging from incubation. We have been researching a fair number of these companies over the last 18 months, and some of these stocks might also join the portfolio in due course.

Regular readers of these quarterly letters are probably also aware that one of the largest holdings in the Panah Fund, a Vietnamese ICT conglomerate,8 is a major beneficiary of increased Japanese IT outsourcing demand for DX services. More than half of sales from the outsourcing division are from Japan. This Vietnamese company’s edge is not just cheap labour costs, but also increasing service quality and the ability to serve clients effectively in Japanese. Sales and orders are seeing healthy growth.

We believe that Japan offers interesting opportunities for investors who are willing to go the extra mile.

Thank you for reading.

Andrew Limond

The original source material has been edited for spelling, punctuation, grammar and clarity. Photographs, illustrations, diagrams and references have been updated to ensure relevance. Copies of the original quarterly letter source material are available to investors on request.

Thanks to Rupert Middle, formerly of Tachibana Securities, for his timely reminder of this Nikkei article.

As Mr Buffett commented shortly after announcing the purchase: “The five major trading companies have many joint ventures throughout the world and are likely to have more of these partnerships. I hope that in the future there may be opportunities of mutual benefit.”

As Mr Suga stated shortly after taking office: “I want to take a proper look at things that are wrong, and move Japan forward by breaking down ministerial divides, vested interests, and a culture of just doing what’s been done before.”

Note that the first and second arrows of Abenomics are respectively ‘monetary easing’ and ‘fiscal policy’.

Note also the surge in replacement sales accompanying the end of Windows 7 support in Jan 2020. Reportedly, ~14mn computers in the country (~20% of the total) were still using this outdated operating system at the start of this year.

For more details, see the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q4 2019 (pp.10-12) and the following Seraya Insight: ‘Why Asia's Market Inefficiencies = Opportunities’.

For a more detailed case study of this investment, please see the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q3 2018 (pp.4-9) and the following Seraya Insight: ‘“Compounders”: The Ultimate 'Lazy' Investment Choice?’.