Making Sense of Markets in the Covid-19 Era: Historical Precedents & What to Expect

The gap between the real economy and the markets, historical analogies, and the 'new normal'

This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

This Insight is an extract adapted from the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q4 2020.1

An investment manager, awaking from a year-long slumber and looking at asset prices for the first time in 12 months, might be forgiven for thinking that the world is experiencing a record economic boom. In 2020, global equity indices broke out to record prices and commodities rallied to multi-year highs, all underpinned by a weak US Dollar and low global interest rates.

In reality, of course, for the last year we have been living through a global pandemic which triggered the most serious worldwide economic downturn since the Great Depression of the 1930s. As of the time of writing, more than 100mn people around the world have tested positive for the SARS-CoV-2 virus, with ~2.2mn reported deaths from Covid-19.2

Government-imposed ‘lockdowns’ designed to slow the spread of the virus led to a collapse in economic activity, hitting the service sector especially hard. More recently, a winter wave of the virus has led to more lockdowns in developed nations. This in turn seems likely to catalyse a double-dip recession in Europe, and possibly also in Japan and the US.

The disconnect between the financial markets and the real economy – as exemplified by stock market performance versus unemployment – has been a source of serious cognitive dissonance for investors, including the Panah team. This growing disparity between stocks and livelihoods also continues to fuel social and political tensions, as exemplified by the turbulent US election process late last year.

All things considered, we believe 2020 to have been the most challenging year so far in our investment careers. It was not just the disconnect between financial markets and the real economy which strained credulity. It was also the speed and extremity of market moves and of the response from policymakers.

March witnessed the fastest market sell-off in history, record-high volatility readings, and a massive policy response (compressing the eight-month policy response playbook from 2008 and more into just eight days). That was followed by one of the fastest equity market rebounds in history, which occurred alongside other unprecedented phenomena such as the price of WTI crude oil falling into negative territory.

Despite these challenges, 2020 ended up being a banner year for equities. The despair of mid-March had transitioned to exuberant, frothy market conditions by year-end.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Making Sense of Markets

Many investors appear to have adopted the view that a major new investment cycle is now in its early stages. According to this view, the coronavirus crisis of March 2020 marks the beginning of a new multi-year economic growth trend, on a par with the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, which marked the start of a new decade-long expansion and a new investment paradigm.

As with all popular investment narratives, there is an undeniable kernel of truth at the heart of this story. After the gradual slowdown in global trade (already in contraction by late 2019) accelerated into a sharp downturn in H1 2020 with the global pandemic shock, there then followed a sharp growth rebound from Q2 2020 which appeared to mark the start of a new global industrial upcycle.3

While we might be in the midst of a shorter global industrial production rebound, we struggle to determine that the coronavirus crisis of early 2020 marked the end of the long business and investment cycle that started in 2009. On the contrary, we think that the current market surge is more likely an extension of the existing decade-long business and investment cycle.

So far, we have seen none of the credit stresses which usually accompany a serious global downturn, as policymakers have used every tool at their disposal to prevent any ‘creative destruction’. Moreover, the outperformers since the ‘coronacrisis’ have been the same sort of stocks which performed best during most of the last decade.

Various indicators of market exuberance – including expensive valuations, record IPOs and M&A activity, a surge in SPAC funding,4 elevated levels of retail participation and so on – also seem to suggest that we are in the late stages of the long cycle which commenced in 2009.

Historical Precedents

At times such as these, we find it helpful to draw comparisons with other periods of history. While no two eras are exactly alike, sufficient similarities can help suggest potential outcomes.

The most obvious parallel to the present is perhaps the Tech Bubble of 1998-2000. The US Federal Reserve (the ‘Fed’) cut rates aggressively in 1998 in response to the LTCM crisis, allowing US equity markets to make a sharp recovery. Even though the Fed did raise rates several times in 1999, it also massively eased liquidity to help head off worries over the impending ‘Y2K bug’. Equity markets – especially tech stocks – rocketed skywards, but the stock market bubble burst after the Fed drained excess ‘Y2K’ liquidity early in the year 2000.

In this case, the massive policy response of March 2020 might be analogous to the LTCM crisis and bailout of 1998; in both cases, massive liquidity helped inflate a bubble in tech stocks. In the case of the Dotcom boom of 1999-2000, the vertical phase of the bubble lasted for 18 months before imploding spectacularly. A double-dip recession followed, with a new global cycle and investment paradigm commencing early that decade with China’s entry into the world trading system and the massive demand shock which accompanied it.

Another less obvious, but equally interesting parallel to the present day are the ‘go-go years’ of the 1960s and early 1970s.5 This era encompassed various booms and busts including the ‘tronics boom’, the ‘synergism’ of the conglomerate bubble, and the surge in the ‘Nifty Fifty’ blue chip stocks. The stories of the excesses have been immortalised in books by authors such as John Brooks and Adam Smith (aka John Goodman).6

The similarities between these booms and the current market situations are clear – it does not take much imagination to see the reflection of the Nifty Fifty in the current ‘FANG+’ names, or the simulacrum of the ‘tronics stocks’ in today’s SAAS stocks and profitless growth counters.

In both cases the bubbles came to a sticky end – the only uncertainty was the timing. After the party was over, the hangovers were spectacular. It took until 2015 for the Nasdaq to regain its March 2000 high, and until 1992 for the S&P to regain its 1968 peak in real terms.

Today’s Markets

Broadly speaking, for the last few years the markets appear to have chosen to distinguish between three types of stocks:

Large-cap oligopolistic tech stocks with strong cash flows and generous valuations (i.e., the ‘FANG+’, etc.);

‘Bubblicious’ growth counters with no profits (and/or questionable unit economics) and large market caps which will supposedly disrupt incumbents, grab market share and generate strong cash flow at some indeterminate future time; and,

The rest, mostly ‘old economy’ companies which trade at cheap valuations.

We can understand why some people choose to buy the first category of stocks, given attractive market positioning and strong cash flows. In most cases, however, our valuation discipline has prevented us from getting involved.

We now see increasing headwinds for the largest tech behemoths (e.g., from anti-trust action and stricter consumer data protection) and think that even if these businesses do continue to prosper in the 2020s, it might take a long time for many of them to grow into their valuations.

We generally have far less interest in most of the speculative stocks which fall into the second category, many of which will probably not fulfil their much-hyped potential. Even those that do are now likely priced beyond perfection.

The exceptions are ‘special sit’ investments in this area where we identify a specific catalyst that might drive near-term upside, especially for firms which dominate a specific niche and can transition into ‘type one’ companies soon.

We also occasionally get interested in speculative ‘type two’ companies with suspicious accounting as these can make particularly good shorts. In the present market environment, however, shorting these names is perhaps a dangerous proposition.

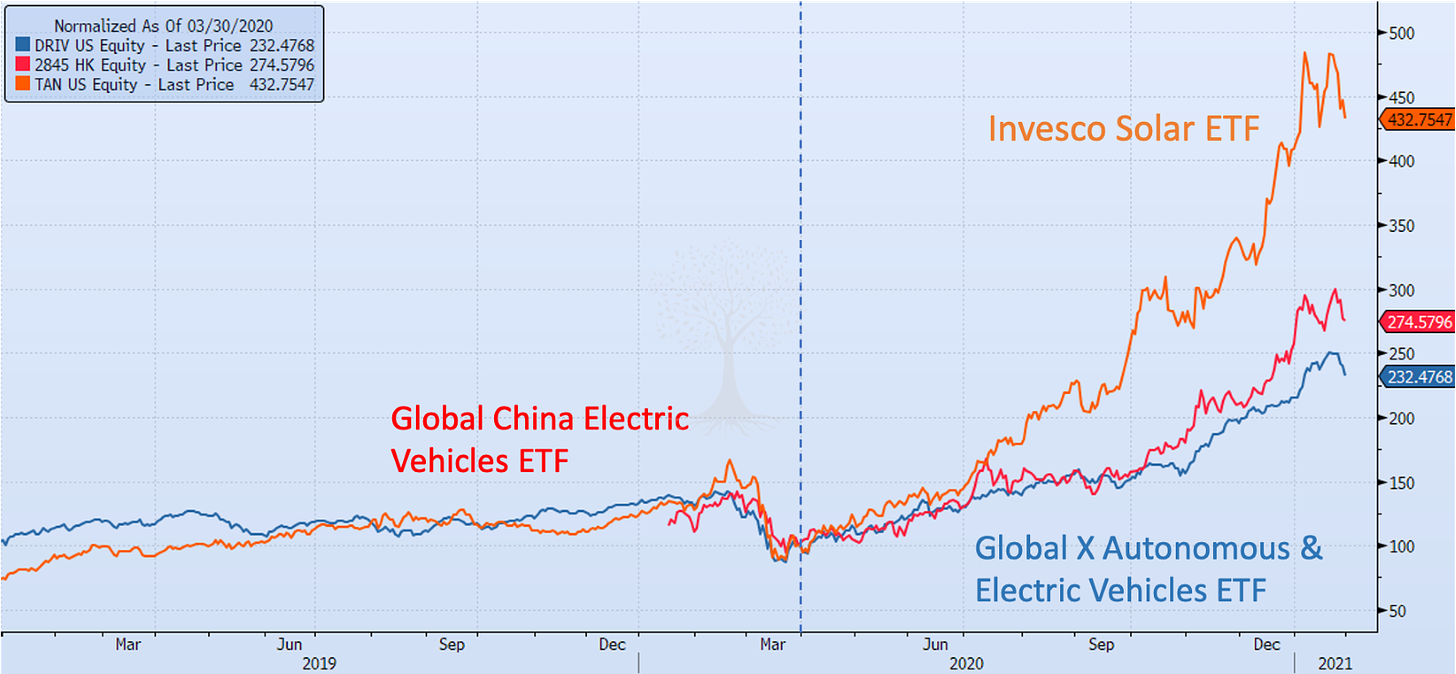

It’s notable that many of the FANG+ stocks have been fairly rangebound since the end of Q3 2020. Instead, it has been a crop of speculative non-profitable tech names and theme stocks, including ‘ESG’ investments such as electric vehicle and solar stocks, which have caught the popular imagination (Figure 3).

Another curious phenomenon since last summer has been the army of retail investors who have focused their firepower and leveraged their stimulus cheques to invest in compromised ‘type three’ companies. (In some cases, these firms were literally bankrupt.) The goal was to massively ramp stock prices in the short-term with no regard for poor fundamentals.

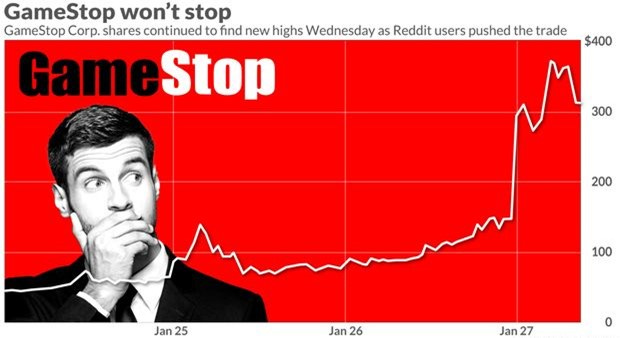

This trend has gone into overdrive in recent weeks as the WallStreetBets Reddit forum7 has successfully engineered enormous short squeezes in stocks with high short interest such as Gamestop and AMC, causing massive losses for some hedge funds who were short.

In an echo of the storming of the US Capitol on 6 Jan 2021, these angry retail investors are pumping a narrative that they are justified in inflicting maximum damage on the hedge funds which are short the stock, whom they believe to represent the plutocratic ‘0.1%’.8 It will no doubt also end in tears for less sophisticated retail speculators who are last to buy this story.

Calling time on such irrational exuberance – especially in a market lubricated by stimulus cheque and central bank largesse – is a difficult task.

So how best to trade these markets, where fundamentals are casually disregarded in favour of a good story?

One of Goodman’s characters, a 1960s money manager named the ‘Great Winfield’, decided that the best way to make money in the great speculative bull runs of the time was to hire only analysts and traders below the age of 30:

“Memory can get in the way of such a jolly market… The strength of my kids is that they are too young to remember anything bad, and they are making so much money they feel invincible. Now you know and I know that one day the orchestra will stop playing and the wind will rattle through the broken windowpanes and the anticipation of this will freeze us.”9

Panah has no plans to hire a new batch of fresh grads who have cut their teeth trading ‘stonks’ on Robinhood. Perhaps we’d have a better chance of gettin’ rich quick by punting these high-octane stocks, but we’d also be far more likely to die tryin’.

Instead, we continue to spend most of our time trying to dig up companies priced as cheaply as ‘type three’ firms, but with business models, cash flows and growth prospects that more closely resemble ‘type one’ companies. These are the compounders that make up the bulk of the Panah portfolio.

Investing in this way allows us all to sleep better at night. Investors should also be aware, however, that this also means that we are more likely to underperform the markets in the sort of speculative melt-up scenario that is playing out now.

Market Outlook and Investment Implications

We enter a new year at record valuations. Markets are pricing in a strong consensus around ‘reopening and reflation’, cheered on by sell-side strategists. The crowd is bullish and appears to be convinced that once the world starts to reopen, then consumers will rush to spend their massive pent-up savings10 which have been boosted by generous government transfers.11 This in turn will drive growth and inflation higher.

Strong momentum might well continue to drive stocks higher in the near-term. From a contrarian perspective, however, this consensus is problematic. If almost everyone is already committed to a trade, then there are fewer people left to buy. “When there is no scepticism, there is almost no one left to sell to.”12

This is not to say that market optimism is set to peak immediately, but it is nevertheless valuable to think about what is driving the reflation narrative and what might derail it.

A Quick Recap

The Covid-19 lockdown slowdown in H1 2020 was short and very sharp. The recovery also proceeded quicker than many expected, especially in those economies which managed to deal with the virus relatively quickly (e.g., China and other Asian countries), helping markets to make a fast rebound. Even as growth started to stall later in 2020, with global output still below pre-Covid levels in most of the world, markets nevertheless remained buoyant.

There seem to be several reasons that markets have been happy to ‘look through the lockdowns’. First, there appears to be a strong expectation that the rapid roll-out of vaccines to combat Covid-19 will proceed without a hitch, allowing life to ‘return to normal’ and growth to rebound. Second, unprecedented easing from central banks has effectively meant that markets are swimming in liquidity. Third, aggressive fiscal stimulus to ‘fill in the gap’ – especially in the Developed World – has been extremely generous, and more stimulus is expected.

For us, the largest surprise of 2020 was that the impact of the coronavirus on the real economy did not lead to more corporate distress and bankruptcies. Government schemes such as furloughs and income support, together with guaranteed banks loans and central bank backing of corporate debt all helped to forestall credit issues. It remains to be seen whether such problems can be held at bay for longer, or whether trouble will emerge in 2021 as the cumulative effect of further lockdowns take their toll.

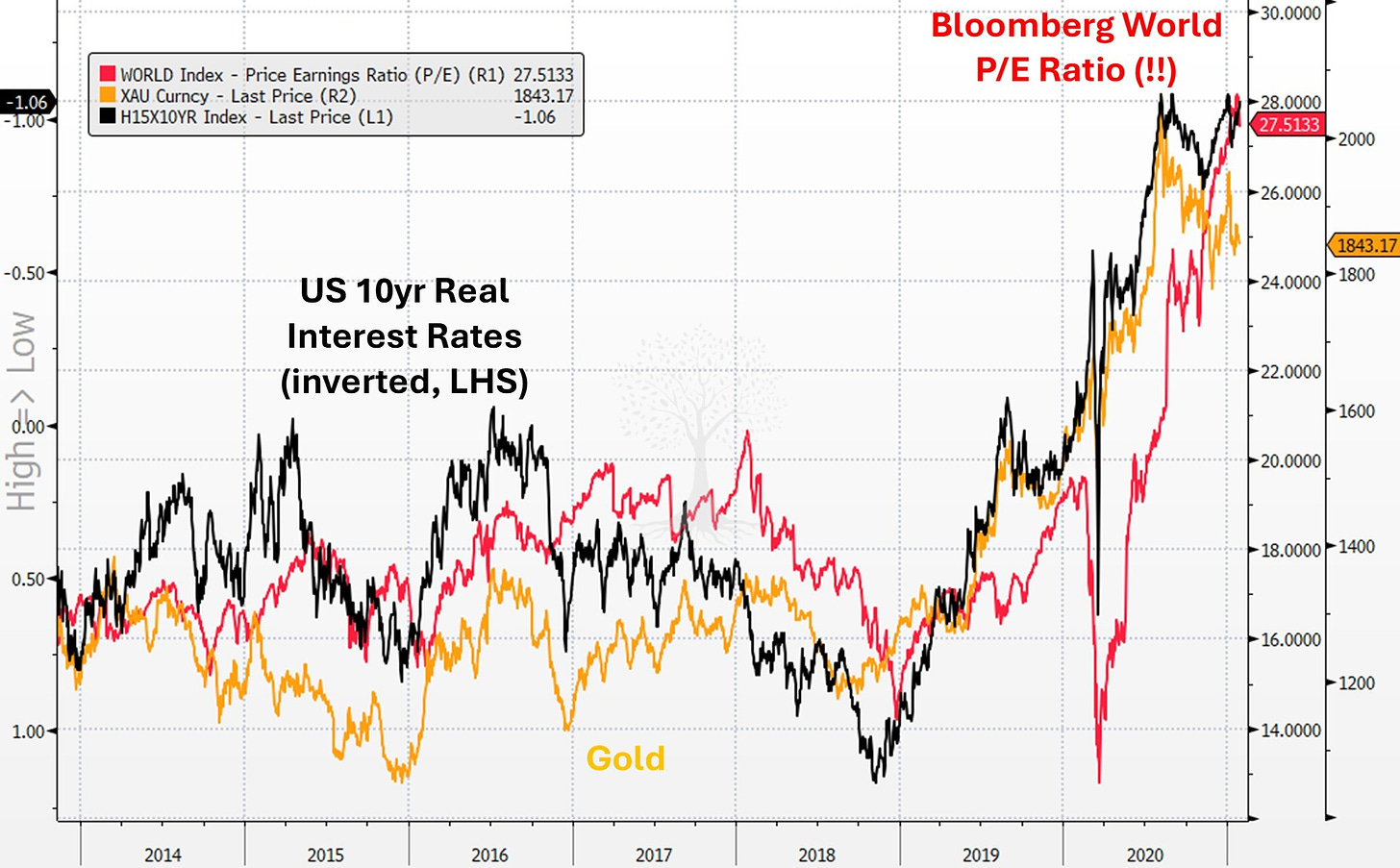

It has arguably been the massive monetary easing which has played the largest role in boosting global equity markets to all-time highs. As real interest rates plunged, asset prices have soared (Figure 5). Growth of monetary aggregates is at all-time highs, prompting investors to ask which assets will keep pace with this ‘monetary devaluation’.

The relationship between market-derived real interest rates13 and asset prices has been particularly pronounced since at least the middle of the last decade: as real rates have fallen, asset prices have risen.

This accelerated from March 2020 with a massive liquidity boost from the Fed in response to the coronavirus crisis. The Fed moved first and moved aggressively, weakening the US Dollar and thereby helping to support international asset prices over the last ten months.

The Rampant Reflation Consensus – What Might Go Wrong?

In the equity markets, the hope is that the ‘reflation trade’ will be manifested in a smooth hand-off between growth stocks and more cyclical ‘value’ investments. A trouble-free rotation would allow equity indices to continue on their upward trajectory.

According to the ‘reflationistas’, US inflation expectations will continue to rise faster than nominal interest rates, keeping real rates low, the US Dollar weak, and asset prices well-supported. Most importantly, central banks will – as they have promised – continue to keep monetary policy accommodative and be more tolerant of higher inflation.

For prudent stock investors, the worry is that the dominance of this reflation narrative and sky-high valuations offer little margin for error. What might go wrong?

First, the winter wave of the virus might not fade with the spring and mutations might prove to be more deadly. The vaccine may not be as effective as we hope, or the roll-out might be delayed. This would likely lead to a more deflationary outcome in the near-term, with the cumulative effect of lockdowns leading to more corporate distress.

Given the strong seasonality of the virus, however, and the fact that reported case numbers for the winter wave are now falling in many countries, we do not place a particularly high probability on this outcome.

Moreover, even if such a scenario does play out, this would not necessarily be bearish for stocks. Instead, equities might start to price in even more fiscal and monetary stimulus in the near-term, allowing markets to continue to look through any double-dip recession. (The likely beneficiaries of this scenario, however, would probably be large cap growth names rather than cyclical value stocks.)

Second, the reflation trade anticipates strong growth momentum as the economy reopens, but this presumes that the fiscal support which has supported growth over the last year will be extended and increased. If more fiscal spending is not forthcoming, then that creates a drag on growth – the so-called ‘fiscal cliff’.

The US ‘Blue sweep’ – cemented by a Democratic victory in two Senate seats for Georgia in early January – has meant that expectations for a US fiscal stimulus are building. In reality, however, it might take longer than markets expect to deliver more stimulus in the US, as it might well rely on the time-consuming and controversial reconciliation process.

In Europe, there seems to be more acceptance of fiscal support, although the political process takes time given the historic resistance from northern European countries to ‘bail out’ their southern neighbours. China is also stepping back from the infrastructure stimulus of 2020.

Everywhere, we see a possibility of tax increases to pay for the extraordinary boost in fiscal spending that has already occurred. Taxes not a market focus right now, although we would be surprised if more attention is not devoted to this topic in H2 2021, perhaps starting in the UK.14

Third, an optimistic Covid-19 scenario might well play out, involving herd immunity by mid-year through natural spread of the disease and vaccination, thereby allowing the economic reopening to proceed.

Even in such a reflationary scenario, however, there is no guarantee that the current ‘Goldilocks scenario’ – with nominal interest rates15 rising at a slower pace than inflation expectations – will persist. Inflation expectations appear to have been ‘artificially’ boosted by Fed purchases and have thus run ahead of the economic recovery.16

The risk is that interest rates will have to rise to bring inflation under control. Any sudden increase in nominal (and real) US yields might well derail the equity rally and trigger a rally in the US Dollar.

Whether or not such an equity market correction would herald a buying opportunity in stocks depends on the reason for the spike in yields. If this were triggered by a some higher-than-expected inflation prints (for instance, as year-on-year base effects kick in from late Q1 and into Q2), then this might be an opportunity to buy the dip.

If, however, investors start to anticipate that any increase in inflation is the start of something more prolonged, they might start to price in a more aggressive Fed tightening cycle. This would probably mean a more serious equity market correction.

Indeed, if markets do start to price in any serious monetary tightening, this would have the potential to make the ‘Taper Tantrum’ of 2013 look like a proverbial teddy bears’ picnic.

In summary, we see the greatest risk to the reflation narrative in 2021 and beyond as inflation and tightening. After all, it was the threat of inflation and tightening which killed the great bull market of the 1960s and marked the peak in the Nasdaq in March 2000.

There are of course a plethora of other external risks which might derail the great stock rally, including cyber warfare and a potential Chinese military invasion of Taiwan. In our view, large scale hacks of power grids and other essential infrastructure are just a matter of time. Meanwhile, the risk of China attempting a forcible reunification17 with Taiwan at some point in the near future is higher than it has been for decades. If any of these sorts of events were to come to pass, all bets would be off for the global economy and markets.

Inflation and Pricing Pressure – Impact on Different Sectors in 2021

The trajectory of inflation vs growth – as well as the areas where price pressures appear – will make a big difference for investors.

As regular readers of our letters know, we think it likely that the world has commenced a secular uptrend in inflation (or ‘stagflation’) that will kick in with full force after the effects of the coronavirus crisis have subsided.18 In the near term, however, we wonder whether one-off Covid-19 effects might have frontloaded the trajectory of the current global industrial upcycle and inflationary pressure, and whether there might be some giveback in H2 2021.

Commodity prices, which have surged over the last nine months, are a case in point. From a fundamental perspective, investors have correctly pointed to years of underinvestment in new mines, as well as a sudden (policy- and virus-induced) surge in real estate demand in the US and China, as legitimate reasons for the rally. There is also the potential for renewed commodity demand in coming years as governments across the world promise more fiscal spending on infrastructure and ‘Green New Deals’.

We detect, however, that resurgent commodity prices (and rocketing shipping rates) have also been driven by strong one-off pandemic demand. Consumers have been unable to spend on travel and leisure services, and instead have stayed at home and carried on clicking the ‘buy’ button on Amazon, Taobao and Lazada. China’s infrastructure spending in 2020 has also supported demand for raw materials and there appears to have been significant onshore inventory-building of industrial metals, although credit is now being tightened.

There have also been serious temporary supply-side disruptions as mine production has been shuttered due to Covid-19. Speculative investment in commodities has also soared, although non-exchange-traded commodity prices are also rising.

What will happen if the global economy does start to reopen in H2 2021? Surely that could mean a switch in consumer spending away from goods and towards services (such as travel and leisure), where there has undoubtedly been an even greater supply disruption during the pandemic? One can easily imagine a scenario, perhaps in mid-2021, where industrial production slows and base metal prices experience a healthy correction, even as the price of an overnight stay in a hotel or a plane ticket spikes dramatically.

Of course, it’s possible that corporate capex might accelerate dramatically in the near future, helping to support the global industrial cycle and pushing commodity prices even higher. There is nonetheless a reasonable possibility that companies will need longer to build sufficient confidence to invest given all that they have experienced during the last year.

A corollary of the potential ‘services rebound vs goods slowdown’ scenario might be the outperformance of the service-heavy, consumption-dependent developed market economies as they get back on their feet following the vaccine rollout. Many Asian and Emerging Market economies, many of which are more exposed to the industrial cycle and/or to commodities, and which either managed the coronavirus better than the US and Europe or will be slower to get vaccines, would presumably receive less of a boost.

In any case, all these possible scenarios and nuances – which are at odds with the current reflation consensus – serve to illustrate that investors ought to remain flexible and balance the probabilities of all outcomes versus market pricing. Naturally, this applies not just at the level of economies and countries, but also sectors and stocks.

The ‘New Normal’?

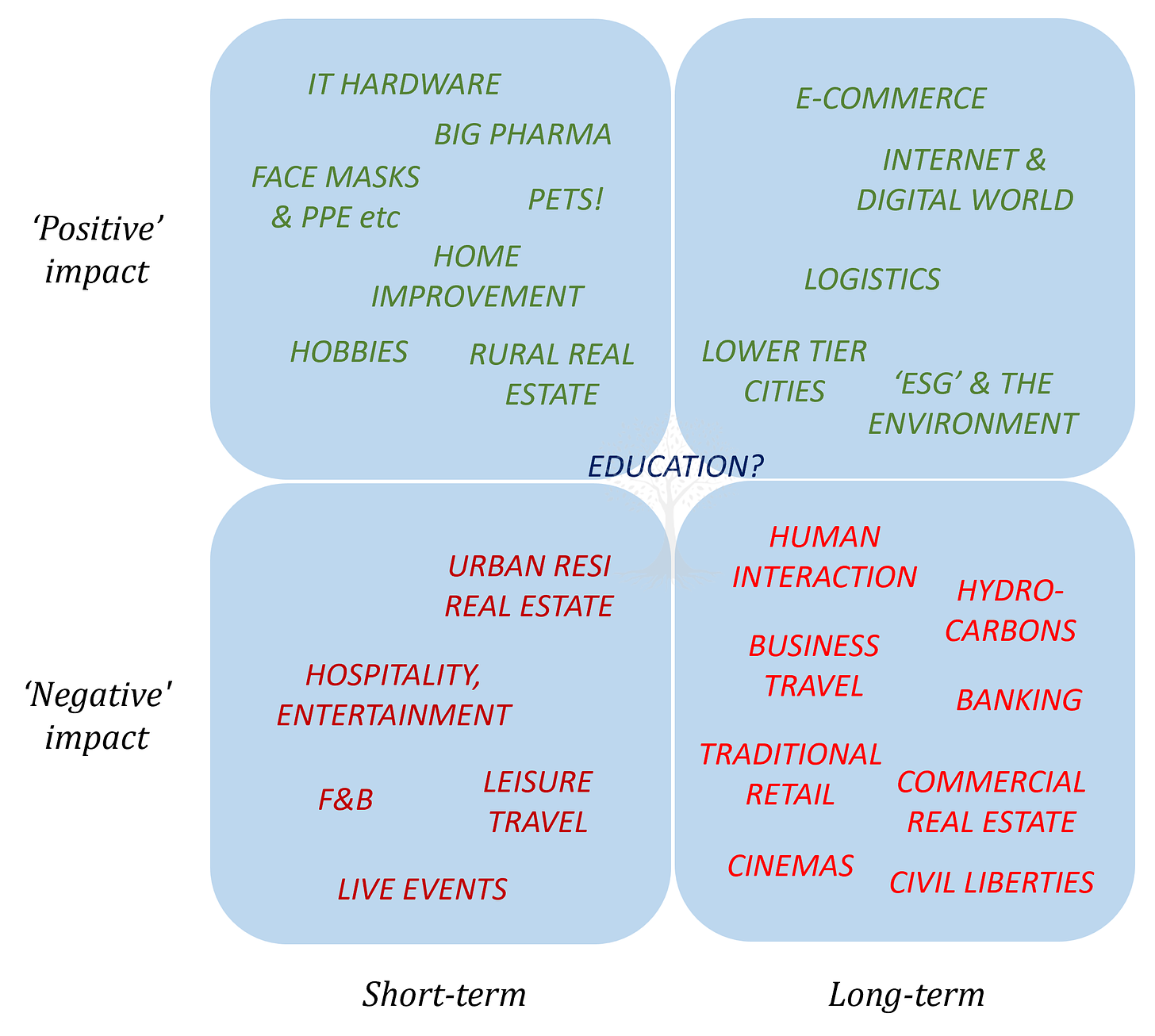

A key question for all investors is what the world will look like after the virus has faded and economies have reopened. Time will tell what the lasting impact of the pandemic will be, but it is important to think about whether the negative and positive impacts on companies and industries are short-term in nature, or whether they might persist for longer.

The quadrants in Figure 8 are a graphical representation of our working assumptions regarding the extent of the positive/negative effect of the pandemic (y-axis) against our expectation for the duration of the impact (x-axis). Others may disagree with some of the specific details of this evaluation, but we hope that it is thought-provoking.

The ‘third axis’, which we do not show on the quadrants but which is most vital for investors, is of course ‘valuation’, in other words, whether sectors and stocks are pricing our expected outcomes. The areas where market pricing confirms our expectations are perhaps less interesting, but discrepancies between fundamentals and valuations might throw up opportunities.

The positioning of some of the sectors in the quadrant might seem self-evident. For instance, it has already become a cliché to talk about how Covid-19 has turbocharged the adoption of technology and e-commerce, and how such trends will only accelerate further. It is thus unsurprising that markets are pricing such an outcome accordingly.

On the other hand, the sudden increased demand for IT hardware to support the new ‘Work From Home’ (‘WFH’) dynamic appears to be temporary surge which has, to a certain extent, frontloaded demand. Supply constraints are now causing component shortages for certain chips and other components, however, which will probably soon squeeze the margins of manufacturers and act to curtail product supply. This is true not just in IT hardware, but also in other sectors such as automobiles. Investors should thus probably expect some ‘giveback’ on these stocks at some point, but this is certainly not yet being priced by markets.

The impact of the pandemic on hospitality and services such as restaurants, travel and leisure – especially in countries which have chosen to implement aggressive lockdowns – has been massive. Business and jobs have been destroyed. Once economies reopen, however, there is a reasonable expectation that demand will surge, benefitting the survivors and improving their pricing power. In general, however, we find that markets are pricing a fairly optimistic outcome for many such companies, and thus have found limited long opportunities in this area.

On the other hand, we expect a longer-term negative impact on commercial real estate, namely traditional retail and office space, especially in certain markets which are heavily oversupplied. This will not be true everywhere, as ongoing WFH will likely be less prevalent in countries which have seen a more manageable impact from the pandemic, as well as certain EM countries where access to technology is constrained. Even in those places where we anticipate an adverse impact, however, long rental cycles mean that this thesis might take some time to play out. Nevertheless, we do expect opportunities to emerge in the coming months and years.

We also anticipate structural changes in the nature of travel. It was a pleasant surprise for the Panah team in 2020 that we were able to transition so quickly from an investment process involving on-site visits, to being able to arrange company calls with existing and prospective investees as more managements became willing to participate in conference calls. (In markets such as Japan, Taiwan and Vietnam where Panah is active, many management teams have historically been reluctant to field calls and have preferred on-site visits from investors.) We sense that this change in attitude is here to stay. Indeed, despite the pandemic, we made more contacts with companies in 2020 than we did in 2019.

There is still undoubtedly a lot of value in visiting companies on-site at their offices, factories and outlets. This is especially true early in the process of getting to know a company and their management team, as it helps to understand corporate culture and management style. In the future, however, we are happy that the widespread adoption of internet conference calls will enable us to do more regular company update calls and reduce the necessity for quite so much business travel. This should hopefully give us more time to think!

Many of the companies we contacted anticipate spending less money on business travel in the future. While a face-to-face meeting with a potential client might be important early in a relationship, it should be possible to rely more on video conferencing to maintain client contact.

In the past, business travel has represented a significant expense for many firms (in the form of business class flights, 4/5* hotel stays, etc.), and so reductions in this area will help the bottom-lines of many businesses. On the other hand, this potential also suggests potential negative ramifications for those hotels and conference centres which rely heavily on business travel, as well as those airlines which make most of their money from selling business class seats.

A recent conversation with a prominent aircraft leasing company suggested that in the future, there will be a transformation in air route selection to emphasise cargo over people. In other words, in the coming years, passengers will hitch a lift with packages rather than route selection being dependent on consumer demand. If this is correct, there might also be knock-on effect for real estate and service businesses in certain cities and locations.

So, while post-pandemic life might return to normal in certain areas, there are also likely to be significant areas of change. Some of these changes might be subtle, and opportunities might emerge in unexpected places. Effective selection of companies and sectors will rely on keeping on top of such developments, as some new trends might be counterintuitive. We thus plan to keep in close contact with a broad range of companies to help us stay abreast of the fast-changing world.

Thank you for reading.

Andrew Limond

The original source material has been edited for spelling, punctuation, grammar and clarity. Photographs, illustrations, diagrams and references have been updated to ensure relevance. Copies of the original quarterly letter source material are available to investors on request.

Data from the CSSE at Johns Hopkins University.

Such inventory-driven cycles tend to be shorter than long business cycles; we think the current upturn might well fade later this year.

Some pundits have characterised the SPAC boom as pure speculation. There are undoubtedly some massive speculative excesses, although the detail is somewhat more interesting and nuanced. What one can say for sure is that the SPAC model has taken off as public market valuations have finally exceeded those in the private markets, as venture capitalists seem keen to cash in. Many SPAC listings will probably fail during the next downcycle.

Hat-tip to John Hempton of Bronte Capital for flagging this period of history for comparison to the present.

Such as ‘The Money Game’ (1967) by Adam Smith (aka George Goodman) and ‘The Go-Go Years’ (1973) by John Brooks.

Tagline: “Like 4chan found a Bloomberg Terminal”.

The reality of the situation is more complicated. Matt Levine gives a good explanation here. The proximate catalyst for the end of the short squeeze might well be that the companies involved attempt to issue more shares.

From ‘The Money Game’ by Adam Smith.

It is notable that these savings are unevenly distributed, and the highest savings are concentrated among those with the lowest propensity to spend (i.e., the wealthy) while others live paycheque-to-paycheque.

Despite the plunge in US activity and employment in the second quarter, personal income rose thanks to massive fiscal transfers.

Also from ‘The Money Game’ by Adam Smith.

Market-derived inflation-adjusted (i.e., real) interest rates are calculated by taking the nominal Treasury yield and subtracting the equivalent yield of the Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities.

In the UK, which seems to have been particularly badly affected by Covid-19, we judge that there is a high probability that a wealth tax of some sort will be introduced in 2021 or 2022.

The Fed has indicated that it will not hike interest rates for some time, so the short end of the yield curve will likely remain anchored for now. The immediate risk would thus be from a sudden spike in yields at the long end of the curve.

Many investors were surprised by the speed at which market-based inflation expectations rebounded following the coronavirus crash in March 2020. Some commentators have pointed out how the Fed has not just been buying regular Treasury securities, but has also been an aggressive purchaser of TIPS. This has ‘artificially’ boosted inflation expectations ahead of any rise in inflation, thereby helping to support asset prices.

While an outright invasion would be risky, under certain circumstances, blockades and other strategies might force Taiwan to the negotiating table.

For more on our stagflationary outlook, please see the Panah letter to investors for Q4 2019 and the following Seraya Insights: ‘Four Big Picture Predictions for the 2020s’. The Panah presentation to investors in December 2020 also provides more information on our view (available on request for investors).