Four Big Picture Predictions for the 2020s

The response to the next crisis will combine monetary and fiscal policy; US-China tensions to worsen; hydrocarbon prices to rise early in the decade; and the re-emergence of inflation

This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

This Insight is an extract adapted from the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q4 2019.1

And so we enter a brave new decade…

Developed countries are keeping their consumption-driven growth models afloat with a mixture of incontinent monetary policy and rising debt levels. Meanwhile, the world is learning to cope with the rise of China, a country which now seems somewhat reluctant to continue blindly with its stop/start credit-driven growth policy. Throw into the mix rising geopolitical, social and environmental challenges, and that makes for interesting times ahead.

The US Federal Reserve’s attempts to raise interest rates in 2017-18 were cut short prematurely as US Dollar real interest rates approached one percent and asset prices wilted. Disruption in repo markets in H2 2019 then led to a renewed commitment from the central bank to expand its balance sheet. Indeed, monetary authorities in developed nations understand that rising debt and asset prices are the shaky foundations on which they have built a significant part of their economies.

Central banks refuse to allow the system to purge itself, which would mean allowing zombie companies to go bankrupt and prudent firms to prosper. Only that way would companies be able to generate higher returns, thereby increasing economic productivity and generating healthy demand-led inflation.

After decades of excesses, however, such an ‘Austrian’ adjustment process would likely be too painful for most political systems to withstand. Instead, central banks are choosing to react to any threat to asset prices by easing immediately, embracing more aggressive Quantitative Easing (‘QE’) and cutting interest rates even further.

Some may protest that this is a poor imitation of how capitalism should work! Maybe so, but it is the system that we have. As investors, we must adjust our expectations accordingly.

Bearing that in mind, we extrapolate from the current direction of world events to suggest several trends which may emerge in the 2020s, together with the investment implications of these developments:

Populist politics will likely demand that the policy response to the next economic downturn involve a greater role for fiscal policy, possibly combined with monetary easing. Although central banks may want to ease further, the unwanted side-effects of ever more negative interest rates are becoming increasingly obvious. In Europe and Japan, financial institutions and savers are coming under increasing pressure as returns fall below zero and capital is slowly destroyed. Rather than spurring lending and creating a trickledown effect, QE is now seen to have exacerbated social inequality. Indeed, rising environmental and social concerns mean that in Europe at least, increased government spending may well be earmarked for a new ‘Green Deal’ and directed towards policies which mitigate social inequality. Depending on how such schemes are implemented, they might well dampen productivity growth even further while also boosting prices. In that case, bond prices would likely suffer.

US-China tensions will continue to rise in the next decade as the two countries’ strategic rivalry deepens. The West had expected that as China became more prosperous, it would also develop along a more democratic path. In the 15 years after China joined the WTO in late 2001, the US thus allowed China plenty of leeway on trade and intellectual property issues. This also suited US business interests, which took advantage of cheap Chinese labour to serve the US consumer. Under authoritarian President Xi Jinping, however, it has become clear that China is seeking to stifle civil society at home and even supplant US hegemony abroad. President Trump has led a tariff-driven backlash against China, and Democrats and Republicans alike now see the country as their main strategic rival.2 Indeed, the US bipartisan political backlash against China may well become the defining legacy of Trump’s presidency. Despite a recent US-China trade truce (which suits both countries in the near-term), there has been no fundamental resolution of various important underlying issues. These include ongoing Chinese government support for key industries, intellectual property theft, and rapid military development. Further measures targeting Chinese tech companies and the country’s capital account seem probable.3 Companies will likely react to such uncertainties by diversifying production, causing bifurcation of supply chains (especially in tech). This will produce losers, but also winners (e.g., in Southeast Asian markets and Taiwan).

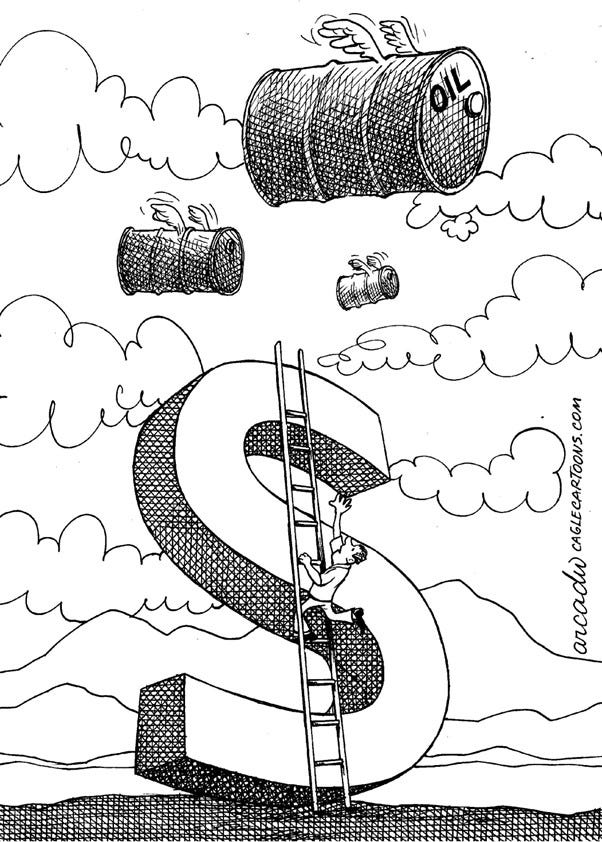

Oil prices will spike early in the decade. This will be driven by disappointing US shale oil production (as decline rates increase), and because ‘climate change’ and ‘ESG’ pressure on hydrocarbon investment will further curtail supply. Geopolitical developments may also provide a catalyst. As alternatives to fossil fuels are not yet ready to pick up the slack, the spike in oil prices would undoubtedly have an adverse impact on the global economy.4 Many industrials and consumer firms would see a squeeze on margins from higher input prices, while out-of-favour energy stocks would rally.

The re-emergence of inflation. The decade since the GFC has been dominated by central bank hyperactivity, which has driven asset price inflation even as consumer prices have remained moribund. We anticipate that the next decade will bring a confluence of factors which catalyse the reemergence of consumer price inflation. Such factors include: a possible peak in the multi-decade globalisation trend (less outsourcing); rising tariff barriers and bifurcation of supply chains (inherently stagflationary); unfavourable demographics (a falling proportion of workers relative to retirees in the developed world); rising anti-trust activity against monopolies and monopsonies (such firms have pushed down wages and prices);5 more pro-active fiscal policy (possibly combined with monetary policy); and underinvestment in energy and certain other important basic materials. The reemergence of inflation would likely cause problems in fixed income markets (especially credit), while gold, energy and value stocks would likely outperform the current crop of popular growth names. Companies with pricing power in an inflationary environment would also perform relatively well. The US Dollar may rally into the next downturn, but then the path of least resistance will be down, driven by ballooning US fiscal deficits and diversification away from the greenback.

Thank you for reading.

Andrew Limond

The original source material has been edited for spelling, punctuation, grammar and clarity. Photographs, illustrations, diagrams and references have been updated to ensure relevance. Copies of the original quarterly letter source material are available to investors on request.

The ‘Report to Congress of the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission’ (Nov 2019) provides an interesting summary of the key issues from a US perspective.

See the Panah letter to investors for Q3 2019 for more details.

We recommend two books which explain the history of hydrocarbons and the importance of fossil fuel for human civilisation: ‘The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power’ (1991) by Daniel Yergin and ‘Energy and Civilisation: A History’ (2017) by Vaclav Smil.

We recommend ‘The Myth of Capital’ (2018) by Jonathan Tepper and Denise Hearn for a robust examination of anti-trust issues. Recent research by Lina Khan has shifted the goalposts on anti-trust and monopoly law.