Evaluating our Four Predictions for the 2020s & the Current Energy Crisis

The world is already experiencing a massive energy crisis, probably the worst since the early 1970s

This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

This Insight is an extract adapted from the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q4 2021.1

In a recent letter to investors2 – published in mid-January 2020 when the idea of a global pandemic was still just a glimmer in the eye of a Wuhan lab bat – we predicted the emergence of several ‘global trends’ in the 2020s.

A summary of the four trends that we suggested in January 2020 and their investment implications follow below:

Populist politics means that the policy response to the next economic downturn will involve more fiscal spending, combined with monetary easing. The fiscal spending will probably be directed towards social and environmental purposes.

US-China tensions will continue to rise in the next decade as the two countries’ strategic rivalry deepens (no matter whether it is a Democrat or Republican in the White House).

Oil prices will spike early in the decade as a result of a lack of investment, US shale output declines, and because ‘ESG pressure’ on hydrocarbons does not allow a supply response to higher prices.3

The re-emergence of inflation, due to a peak in the multi-decade globalisation trend (less outsourcing); rising tariff barriers and bifurcation of supply chains (inherently stagflationary); unfavourable demographics (a falling proportion of workers relative to retirees in the developed world); rising anti-trust activity against monopolies and monopsonies (such firms have pushed down wages and prices); more pro-active fiscal policy (possibly combined with monetary policy); and underinvestment in energy and other important basic materials. The re-emergence of inflation will likely cause problems in fixed income markets (especially credit), while gold, energy and value stocks will likely outperform growth names. Companies with pricing power in an inflationary environment will also perform relatively well. The US Dollar may rally into the next downturn but then the path of least resistance will be down, driven by ballooning US fiscal deficits and diversification away from the greenback.

Over the last two years we have seen the emergence of all four of these trends, catalysed and accelerated by the global response to the pandemic.

While the first two trends are already well entrenched, the third and fourth trends are at earlier stages in their development.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The Resurgence of Inflation

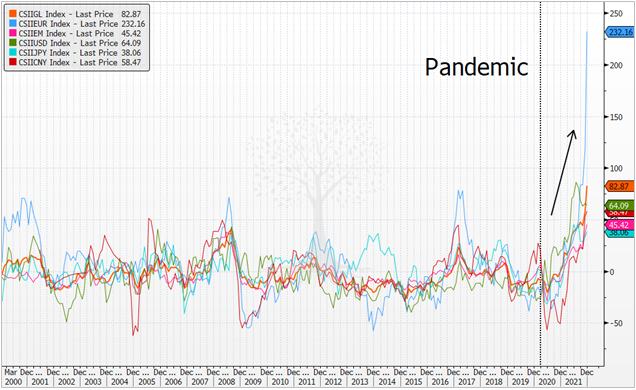

It is an indisputable fact that inflation has re-emerged as a global force since the pandemic (Figure 1). There is still some dispute, however, as to the causes of inflationary forces that the world is currently experiencing.

Is inflation structural, as we expected, or instead ‘transitory’, as a result of supply chain disruptions? In that case, will inflation settle down as supply chains normalise and factors such as aging demographics and technology reassert themselves?

In the US, confident expectations for an imminent fall receded in late 2021. This was as the Federal Reserve (the ‘Fed’) realised it might be making a serious policy error, dropped its ‘transitory inflation’ terminology, and scrambled to bring forward its timetable for monetary policy tightening. In early 2022, this ‘hawkish pivot’ has been one of the major factors roiling equity markets.

Base effects might well mean that year-on-year inflation measures peak in the coming months and start to roll over. After an initial retrenchment, however, we would not be surprised to see inflation stay more persistently sticky in the coming years, running at higher levels than in the last decade.

The investment implications of higher inflation are still at a relatively early stage. While energy and materials stocks already rallied from last year, ‘value’ stocks (especially in the energy sector) have only just started to turn the corner against growth equities. Inflation- and wage-driven margin compression has only just begun.

The gold price has been somewhat subdued in the last 18 months (playing second fiddle to industrial metals and cryptocurrency). Developments in the fixed income and credit markets have so far been orderly – though this might not persist in 2022.

The World is Already Facing a Massive Energy Crisis

Moving back to the third trend… Our expectation for an oil price spike early in the decade, premised on a supply shortfall, has not played out exactly as anticipated.

In March 2020, at the same time the ‘coronacrisis’ struck, Russia and Saudi Arabia unexpectedly failed to reach an agreement to restrict oil production. This led Saudi Arabia to announce on 7 March 2020 that it would instead adopt a ‘pump-at-will’ policy.

During the next eight weeks, the sudden OPEC+ supply glut, combined with anticipated dramatic demand destruction from the global pandemic lockdowns and travel restrictions, catalysed a sharp plunge in the price of oil. As oil storage filled up at Cushing, Oklahoma, the settlement price for May 2020 Nymex West Texas Intermediate oil futures contract went negative for the first time in history.

Since that time – as supply discipline returned to OPEC+ and as initial strict Covid-19 ‘lockdowns’ were reversed – the price of oil has staged a dramatic recovery. This is despite significant ongoing demand destruction due to on-off lockdowns and travel restrictions. The price of a barrel of oil now stands at a higher level than in early 2020, before the pandemic.

Even more remarkable, however, has been the immense surge in other hydrocarbon prices in the last two years. Gains in most other hydrocarbon prices (i.e., coal and gas) have massively outstripped the gains from oil prices since early 2020.

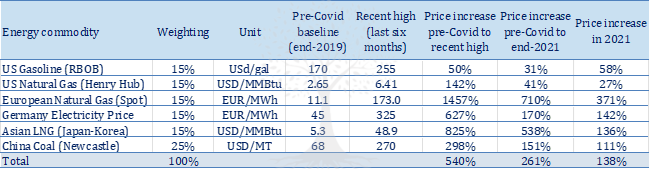

A global basket of energy prices4 rose +138% in 2021, and as much as +540% from a pre-Covid baseline at end-2019 to the recent highs – a massive increase (Figure 3).

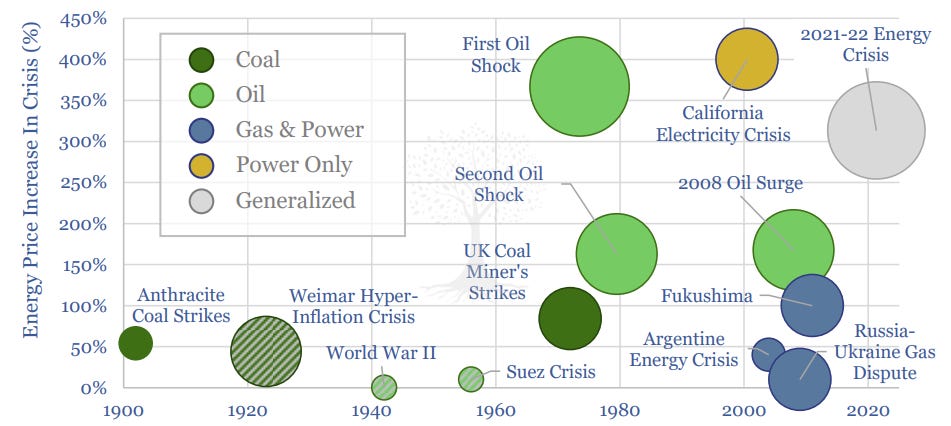

It seems clear that the world is already experiencing a historically significant energy crisis. Unlike previous energy crises, this one is widespread and affects most forms of hydrocarbons in most geographies.

Despite the rising importance of other energy sources in recent years (such as renewables and hydroelectricity), in 2020, hydrocarbons still accounted for an estimated ~83% of the world’s primary energy consumption.5

The world economy still runs on fossil fuels.

This crisis has already surpassed the 2008 oil price spike in terms of both magnitude and duration (Figure 4). It is not quite yet on the same scale as the First Oil Shock of 1973, which was triggered by the Yom Kippur War.

Given the current tight supply-demand situation and the difficulty in increasing hydrocarbon supply because of ESG-driven funding restrictions, however, it is conceivable that this might yet become the most severe energy crisis ever.6 Potential geopolitical shocks (e.g., Russia-Ukraine, the UAE) present a further upside risk to energy prices.

The knock-on effect of soaring energy prices to other industries has been severe – metal smelters, as well as fertiliser and other chemical plants around the world have been shuttered because of high energy costs. The prices of these commodities have soared. The implications for agricultural production and other forms of economic activity in 2022 will likely be significant.

Why aren’t the newspapers reporting daily on this historically significant energy crisis? While there has been some media attention, this issue has not garnered the attention we believe it deserves.

This is probably because the price of oil remains the most obvious ‘energy price’ for most of the world’s population. The price of fuel is visible every time anyone drives past a petrol station, and gasoline price gains have so far lagged those of other hydrocarbons given the outsized impact of pandemic travel restrictions on gasoline compared to other fuels.

As mobility increases, so will gasoline demand. Newspaper headlines probably won’t start screaming about an energy crisis until the oil price rises above US $100/bbl. Watch this space.7

The fundamental nature of this crisis – driven by years of underinvestment and by a misguided notion that the world should starve itself of fossil fuels before sufficient ‘new energy’ infrastructure is in place to pick up the slack – suggests that energy prices have further to run. Even if seasonal factors pull down gas and coal prices in the spring, we believe that the world is now facing a rolling energy crisis which will probably drag on into the mid- to late-2020s.8

As the reality of higher prices bite, consumers and governments will likely be forced to reconsider their previous assumptions that the world can undertake an unprecedented ‘energy transition’ without incurring substantial costs. Dramatic decarbonisation might well be desirable for the planet, but it will require significant sacrifices on behalf of the world population – the price of ‘virtue’ is expensive. In 2022-23, it is plausible that spiralling energy prices might even precipitate a recession.

In this gap between ‘ESG’-driven public perception and the economic realities of the energy transition, we believe there exist various opportunities for investors who are willing and able to keep an open mind. It should be possible to reach ‘Net Zero’ carbon emissions by 2050, although probably not in the manner that the consensus currently expects.

It is beyond the scope of this letter to write about all the investment implications of all these views, and indeed our own research in this area continues. Watch this space.

Regular readers of our letters should already be aware that Panah has been involved in investing in uranium, one of the ‘highest beta’ energy investment opportunities, for the last three years. Not only are the supply-demand dynamics for uranium extremely tight, but we also believe that nuclear power is essential to achieve global decarbonisation goals.

In January 2022, investors have been focused on the central bank tightening narrative. We expect market attention to shift back towards energy in the coming months.

Thank you for reading.

Andrew Limond

The original source material has been edited for spelling, punctuation, grammar and clarity. Photographs, illustrations, diagrams and references have been updated to ensure relevance. Copies of the original quarterly letter source material are available to investors on request.

See the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q4 2019 (pp.12-13) and the following Seraya Insight: ‘Four Big Picture Predictions for the 2020s’.

‘ESG’ stands for ‘Environmental, Social & Governance’ issues. While ESG incorporates many aspects of sustainable investment, in recent years there has been a particular focus on ‘climate change’ and ‘decarbonisation’ as a priority. In reality, sustainable investing encompasses a far broader set of ESG issues than decarbonisation alone; some of these other issues are also perhaps unduly neglected as a result of this focus.

This global energy basket encompasses: US gasoline, US and European nat gas, Asian LNG, Chinese coal, and European electricity prices.

See the BP 70th Statistical Review of World Energy, 2021 (p.11).

There has been ‘ESG pressure’ on hydrocarbon producers as the combustion of these fuels is responsible for carbon emissions which thought to be responsible for climate change. Investors and lenders are thus being encouraged to deny funding to hydrocarbon producers, leading to a rise in their cost of capital. Moreover, these companies are also being pushed not to increase production of hydrocarbons given the environmental impact of these emissions. As a result of this ‘ESG pressure’, it thus seems likely that even as the price of hydrocarbons rise, the usual supply response (i.e., higher prices lead to higher investment and production) will not hold. This might cause hydrocarbon prices to stay higher for longer.

The most recent IEA latest outlook for 2022 is somewhat sanguine, although the latest alarming discrepancies with the latest IEA inventory data (i.e., 200mn barrels of oil is ‘missing’, suspected consumed) should give pause for thought.

Our view is that while an ‘energy transition’ towards a lower carbon global economy may well be desirable, it would be foolish if the world were to suffer an energy shortfall during this period as a result of invalid assumptions and bad planning. Indeed, any serious shortfall in energy supply would probably lead to much higher prices, thereby destabilising various energy-consuming economies and societies around the world. Careful planning is necessary.