Covid-19: the Catalyst for a Massive Shift in the Zeitgeist

Our initial reaction to the pandemic: how the coronavirus crisis will catalyse a massive shift in the Zeitgeist, and why we expect a stagflationary outcome

This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

This Insight is an extract adapted from the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q1 2020.1

Once every generation or so, there comes a moment when a multitude of deep-flowing global social, economic and geopolitical undercurrents well up to the surface and flood together in a single defining event which lays bare the world.

The last moment of this type was probably the Fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, a deeply important and symbolic event which marked the end of the Cold War.

We believe that history will see the SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 coronavirus crisis of 2020 – which struck the world at a vulnerable moment – as a turning point of similar magnitude. This is not necessarily due to the nature of the virus itself, but because of the way in which mankind is reacting to the challenges that the disease has presented.

In this note, we attempt to draw out the social, economic, geopolitical and investment consequences of this watershed moment.

We also attempt to answer the following questions: what just happened and why; how are we positioning the portfolio; and what does this mean for the world in the 2020s?

TABLE OF CONTENTS

A Review of Recent Events

The Public Health Response to the Virus

The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, which causes the disease COVID-19, reportedly originated in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China in November 2019. Although the disease was at first confined to China, more than 2.2mn cases have since been discovered in more than 185 countries, causing at least 150,000 deaths.2 As the disease spread in March, panic spread in the stock markets and catalysed a market crash.

The world’s first line of defense against the virus has been the response from the public health and medical authorities. Very little is still known about the epidemiology and pathogenesis of the virus, including hospitalisation and death rates. Many countries have thus decided to introduce ‘lockdowns’ orders to keep people at home, thereby slowing the rapid spread of the virus and reducing the risk that their healthcare systems are overwhelmed by patients who need treatment in intensive care units and with ventilators.

Here in Kuala Lumpur, a government-mandated Movement Control Order (‘MCO’) has been in force since 18 March. Under the terms of the MCO, people are only permitted to leave home to access or provide essential services (such as buying food and daily necessities or for medical reasons); it is enforced by police and army personnel who man roadblocks. Thousands of people who have violated the MCO have been arrested and charged, including joggers and dog-walkers. The MCO has already been extended twice, most recently until 28 April. Some expect it to be extended for even longer, possibly until after Hari Raya in late May.

While ‘lockdown’ measures may well make sense as a temporary emergency response to an extraordinary public health challenge, the potential economic cost of such policies is simply staggering. The longer that the lockdowns continue, the higher the risk that such policies cause serious and lasting damage to the global economy, with a knock-on effect to health and mortality that may eventually be greater than the virus itself. Balancing public health priorities and the economy is an almost impossible task for policymakers, and it is being compounded by a lack of accurate information and data about the virus.

As always, at times like these it is the poorest countries and individuals who stand to suffer the most. There have been shocking scenes in countries such as India as millions of migrant workers flee urban slums and walk hundreds of miles back to their villages.

Developing countries in general have the most fragile healthcare and welfare systems, and it is the poorest inhabitants of these countries who are most vulnerable. This, however, is a problem for everyone in the world. If the virus becomes endemic in less developed countries among groups of people who do not have access to adequate healthcare, this creates a source of reinfection for the rest of the world.

The global sectors shouldering the largest financial burdens as a result of the outbreak are of course travel, leisure, transportation and retail. If not for government support, many firms in these sectors which have experienced a ‘sudden stop’ would almost certainly face bankruptcy.

Workers in these sectors and those who are part of the ‘gig economy’ have been disproportionately impacted by the lockdowns, as many have been furloughed or lost their jobs in recent weeks. The rapid rise in unemployment is historically unprecedented and can be expected to worsen (Figure 3).3

Striking a Balance between Public Health and the Economy

Brave healthcare professionals around the world are risking their lives to save others. Scientists are working round-the-clock to develop treatment regimens and eventually a vaccine. In time, they will almost certainly succeed, and human ingenuity will triumph.

In the midst of the current crisis, however, we ought not to lose sight of what is arguably the most critical near-term public health and economic priority: to carry out representative and random antibody tests to determine the true size of the outbreak in the population.

Why is this so important? Widespread antibody (serological) testing is required to give us a clearer picture of the ‘denominator’, i.e., the number of people who have already been exposed to SARS-CoV-2. Many of these people may be asymptomatic or not currently included in the statistics, although they should have already acquired immunity.

Without a clearer idea of the actual spread of the disease, hospitalisation and death rates are also just guesswork. But it is precisely this fear of hospitals being overwhelmed which is prompting governments around the world to enforce economically damaging lockdown policies.

If serological tests show a high number of cases, with ~50% of the population already having been infected (as hypothesised by a recent Oxford University study), then that would imply that we are close ‘herd immunity’ already and that hospitalisation and death rates from the disease are relatively low. ‘Stay at home’ policies could thus be eased fairly quickly.

In such a ‘best-case’ scenario, it might only be necessary for the elderly and vulnerable to self-isolate for a period of time, while the rest of the economy could get back to work.4 The damage to the economy would still be serious, but it would be time-limited and – with sufficient stimulus – would allow for a ‘V-shaped’ recovery.

If, however, serological testing shows that only a small proportion of the population has already been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 (as suggested by the notorious Imperial College study), that would imply much higher hospitalisation and death rates. In this worst-case scenario, any relaxation of lockdowns would likely lead to a rapid resurgence of infections and a serious risk of national healthcare systems being overwhelmed by patients.

Political leaders would thus be faced with an unenviable choice between deep economic recession and high mortality rates. They would probably choose to implement on/off lockdowns for most of the next ~18 months, in response to outbreaks, until such time as a vaccine might be developed.

The longer the lockdowns continue, however, the more likely that temporary liquidity issues become serious solvency problems. After a few months, cash-strapped businesses would start to go bankrupt. Certain assets (e.g., commercial real estate) would be impaired and may never fully recover their value. There would be a serious knock-on effect to the banking system, and the damage to economies and societies around the world would be catastrophic. The world is simply too indebted to be able to continue with lockdowns indefinitely.

In reality, the truth probably lies somewhere in between these extremes. That might imply several months of stop/start lockdowns as the disease ebbs and flows. We are already seeing such a phenomenon in certain Asian countries, as initial outbreaks were brought under control, but then new infections surged as travellers brought the disease back from Europe and the US.

There may be some relief in the northern hemisphere summer, if SARS-CoV-2 follows a similar seasonal pattern to other coronaviruses and spreads more slowly in warm and humid weather.

In the coming months, it may be that we also find effective treatments for the virus (perhaps including drugs such as hydroxychloroquine and remdesivir) that help to reduce mortality rates and allow COVID-19 patients to make a faster recovery. On the other hand, it may be that the virus mutates and comes back in another form later this year.

How close are we to mass-producing the accurate antibody tests that will allow us to grasp the extent of the pandemic? Every day brings news of another company trying to produce such tests, and governments attempting to introduce testing programs. So far, however, there seem to have been serious issues in terms of accuracy and reliability. Realistically, it seems overoptimistic to hope for the mass production, deployment and analysis of such tests before the end of May at the earliest. The uncertainty thus seems set to continue for a while longer.

Once antibody tests are able to be successfully deployed, another additional benefit would be that it would allow those with existing immunity to return to work first and help get the global economy back on its feet. Such testing will likely also be necessary to allow people to start travelling again, albeit in a bifurcated world: between countries that have managed to bring the virus under control (largely in Asia) and those which have failed to do so (the US, Europe and most other Emerging Market (‘EM’) countries).

Ironically, the same countries which have been most successful in keeping out the disease are the ones which will have to maintain the tightest travel restrictions.

The Monetary and Fiscal Response: to ‘QEinfinity’ and Beyond + Aggressive Deficit Spending

The uncertainties surrounding the virus are enormous, which means that the range of possible outcomes for the global economy are still extremely wide. The first reaction of most policymakers around the world has been to rush and try to fill the gap in aggregate demand by extending massive fiscal support, and to ease monetary policy as aggressively as possible to prevent any serious problems arising in financial markets. After all, they don’t want a financial crisis on top of a public health crisis.

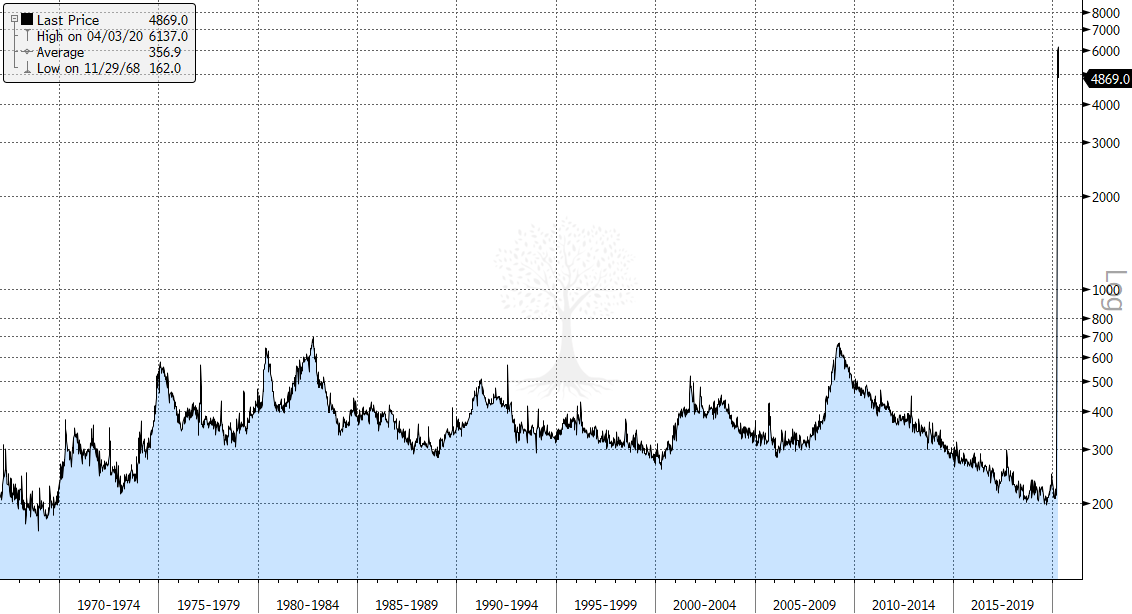

Indeed, the US Federal Reserve (‘the Fed’) took just eight days in mid-March to adopt almost the full panoply of policies that it took eight months to introduce during the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-09. These included cutting interest rates to the zero bound, unlimited Quantitative Easing (‘QE’) or ‘QEinfinity’, backstopping money market funds, extending US Dollar swap lines to various other central banks, and an alphabet soup of other programs to support other dysfunctional corners of the market.

The Fed then went one step further by agreeing to buy investment grade debt in the secondary market, taking on non-government credit risk for the first time. This was followed soon afterwards in early April by a commitment of US ~$2.3tn in loans for small- and medium-sized businesses, state and local governments, and even some types of high-yield bonds, collateralized loan obligations and commercial mortgage-backed securities.

Some commentators have described these dramatic developments as the Fed going ‘nuclear’. We find it hard to disagree, given that the central bank’s balance sheet has already expanded from US $4.1tn at end-February to $6.3tn now, and is expected to reach ~$10tn by the end of the year – half of US nominal GDP.

The governments of most developed nations have introduced multi-pronged fiscal packages, many of which are set to extend in excess of 10% of GDP in stimulus to offset the effects of the virus lockdowns.

In the United States, the US ~$2tn CARES Act, passed in late March, mandates cash payments from the government to households, help for small businesses, and support for local government and companies such as airlines which have been particularly badly affected by the crisis. This will likely push the US fiscal deficit towards ~20% in 2020.

The biggest challenge for the US will be to get the money to the neediest recipients on a timely basis. (In contrast, certain European countries may find this easier because of more comprehensive welfare systems and a focus on income support.) The risk of delays and misallocation of aid money in all countries is high.

The Dawn of Debt Monetisation

As part of the CARES Act, Congress authorises the US Treasury to provide US $454bn of funding which will be levered almost tenfold by the Fed to provide ~$4tn in funding to support the economy. The Treasury and the Fed will work together to provide these programs, blurring the line between fiscal and monetary policy.

While such a measure may not quite meet the exact definition of debt monetisation, such cooperation between the Treasury and the Fed means that a red line has already been crossed. Meanwhile, the UK government – worried that it would no longer be able to access the gilts market – has explicitly adopted debt monetisation by increasing its account with the Bank of England (the ‘Ways & Means Facility’) to an unlimited size.

The Fed’s decision to intervene in credit and muni markets – effectively giving it the ability to pick winners and losers in the private markets – also marks an unprecedented development in the history of US capital markets.

Polonius warned us to “Neither a borrower nor a lender be”. Fed Chairman Powell, on the other hand, seems to be rather more sympathetic to borrowers than lenders – moral hazard be damned.

While the Fed has not yet started to follow the Bank of Japan into purchasing listed equities, former chair Janet Yellen has called for Congress to change the law so as to allow the Fed to do so in future.5

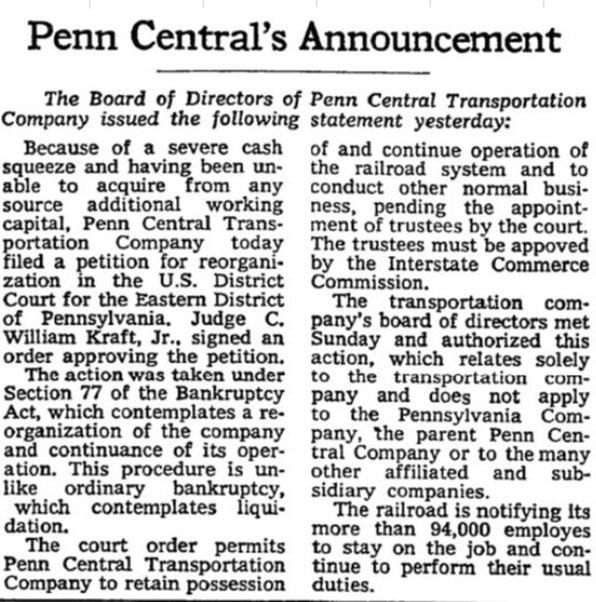

All of these extraordinary developments bear witness to the fact that rising debt and asset prices are the shaky foundations on which most developed countries have built their economies. Each time that a financial crisis strikes – a feature of the system, not a bug – central banks have felt they have little choice but to throw more and more money at the problems which emerge, and so debt levels continue to rise.

This might reduce pain in the short-term, but it also prevents the system purging itself through bankruptcy and economic renewal. It also encourages more risky behaviour. With each cycle the imbalances have grown, distorting the edifice of the economy. In the US, it started with the Penn Central Railroad bailout of 1970.

Fast forward to the 21st century, and central banks now dare not allow the system to clear. They fear that economic, social and political systems might not survive the aftermath of such a decision.

In past letters,6 we have warned that the government response to the next downturn will likely involve policymakers choosing to conflate fiscal and monetary policy. That moment now seems to have arrived.

The US government decision to mail cheques directly to households, even as the Fed offers unlimited liquidity and direct financing of fiscal programs, appears to be the first manifestation of ‘helicopter money’. Japan is also set to give cash handouts to households. Such programs may also mark the first hesitant steps towards the introduction of Universal Basic Income (‘UBI’).

What is perhaps most remarkable is how quickly the menu of publicly acceptable policy options (i.e., the Overton Window) has expanded since the start of the year as a result of the coronavirus crisis. Radical wealth redistribution proposals such as UBI, as well as barely credible academic prescriptions such as Modern Monetary Theory (‘MMT’), are already going mainstream.

As we transition to a post-virus world, western governments will be under pressure to act swiftly to boost their economies. We think it likely that stimulus packages to reboot the economy will focus on infrastructure, and on tackling such issues as climate change and promoting green energy (e.g., the European ‘Green Deal’, and in the US, the ‘Green New Deal’ or a Republican equivalent which may involve more nuclear power).

In our view, over time the ‘temporary crisis measures’ adopted in early 2020 are more likely to be expanded than reversed. Casting our minds back to the introduction of QE during the Great Financial Crisis, we recall how the Fed’s balance sheet expansion was meant to be limited in time and scope.

In reality, however, QE and other extraordinary policy measures have since become a part of the standard toolkit for global central banks around the world. After all, in the oft-quoted words of Milton Friedman, “Nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program.”7

Public opinion has shifted abruptly to the left. In the words of a recent Financial Times editorial (3 April):

“Radical reforms — reversing the prevailing policy direction of the last four decades — will need to be put on the table. Governments will have to accept a more active role in the economy. They must see public services as investments rather than liabilities, and look for ways to make labour markets less insecure. Redistribution will again be on the agenda; the privileges of the elderly and wealthy in question. Policies until recently considered eccentric, such as basic income and wealth taxes, will have to be in the mix.”

In short, the coronavirus crisis has catalysed a rapid shift in the zeitgeist. The investment implications of these changes will be profound.

Market Dynamics

The world is now facing a historically unprecedented deflationary shock as much of the world’s population is locked down at home and demand evaporates. World markets are locked in an uneasy dance between colossal coronavirus demand destruction and a massive boost from combined fiscal and monetary policy.

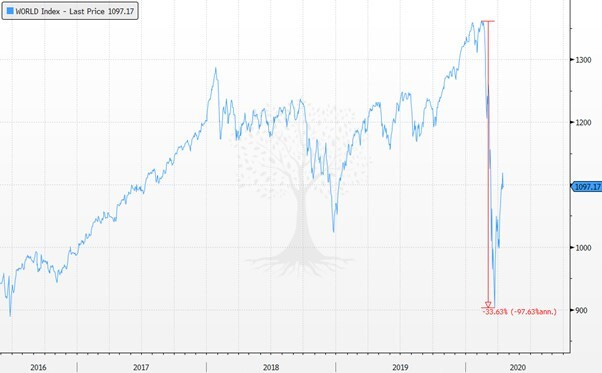

As investors became more concerned about the impact of COVID-19, the Bloomberg World Index plunged by one-third from mid-February to mid-March, which included the fastest >20% US stock market sell-off in history (Figure 7). Since then, the strong fiscal and monetary response has enabled a speedy rebound which has retraced almost half of the losses. Market sentiment has apparently also become more optimistic as lockdowns appear to be slowing the spread of the virus.

Investors now seem to have split views on the future path of the economy and stock markets. There are those who believe that the stock market has already bottomed. They expect the virus to fade quickly, allowing for a V-shaped economic recovery which will propel stocks to new highs, turbo-charged by a low oil price and plenty of fiscal and monetary stimulus.

There are others who believe that markets have further to fall following the current bear market rally. They expect the effects of the virus to be with us for much longer, causing a massive hit to the economy which cannot be fully offset by government and central bank accommodation. Liquidity surges alone will not be able to paper over the massive hits to nominal GDP and earnings, and so stocks will fall.

The markets will also have further risks to grapple with in the remainder of the year. The US presidential election is certain to be hotly contested. As the campaigning ramps up, the Democrats and Republicans seem almost certain to vie to outdo one another on ‘bashing China’. US politicians are already getting increasingly vocal about the global cost of China’s alleged cover-up of the disease. Further escalation of the US-China tech war also seems possible.

The situation in the Eurozone also has the potential to deteriorate further, as the coronavirus has exacerbated divisions. The key question is whether the northern countries are prepared to take further steps towards fiscal union (e.g., by issuing ‘Coronabonds’) in order to support their unfortunate southern neighbours who have been wilting under the pressure of COVID-19.

While credit lines from the European Stability Mechanism may be sufficient to fudge this issue for the time being, these questions will no doubt re-emerge once the time comes for a post-virus stimulus package to reboot the Eurozone. In particular, Italy and Spain are suffering badly, and would not react well if they do not receive the support they feel is due. The implications for the sustainability of the Euro are of course profound.

In reality, given the massive uncertainties surrounding the development of the virus and the public health response, nobody knows exactly what path the global economy and markets will follow in the coming 12-18 months. Given the large range of possibilities, we thus believe it makes sense to stay flexible rather than fixating on one potential outcome.

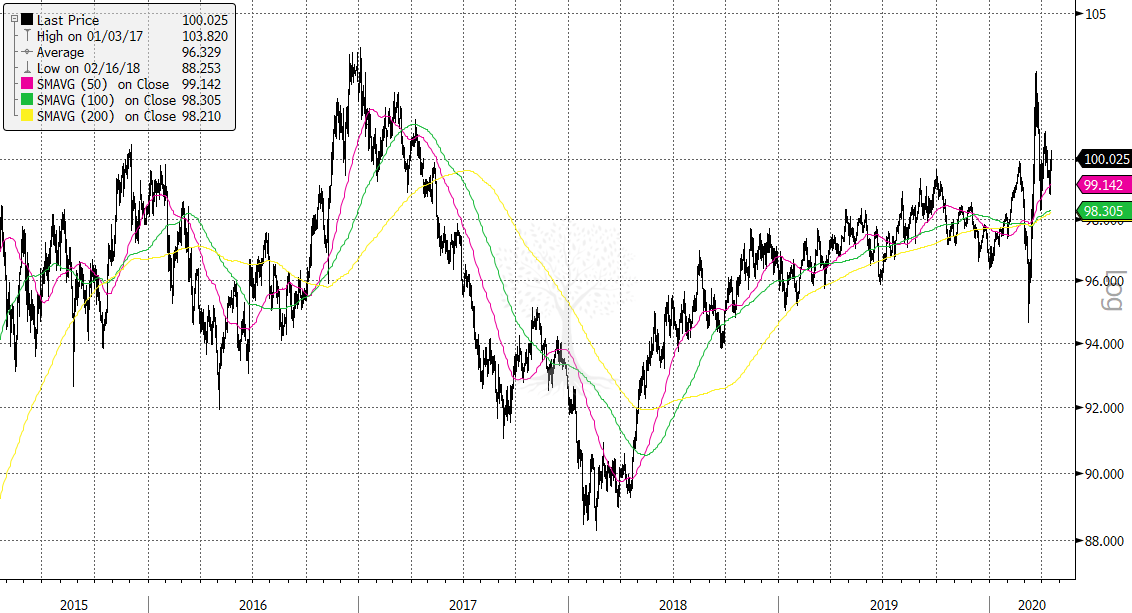

Various indicators are useful to track the battle between the deflationary forces of the disease and the reflationary impulse from central banks and governments. If we were forced to choose only one metric to monitor, however, we would probably opt for the US Dollar – the ultimate gauge of market liquidity (Figure 8). A weakening Dollar trend should be good for asset prices, all else being equal. A stronger Dollar might be a harbinger of renewed stress.

It is important to remember that portfolio outcomes are not just about market beta! Although stock correlations converged during the most violent phase of the market sell-off in mid-March, more differentiation between stocks and sectors has emerged as equity volatility has started to subside. The crisis has thrown up some interesting opportunities to make money in various sectors, some familiar and others new.

A Brave New Decade: Getting Ready for the Next Cycle

In each of the last few decades, different stocks have led the market in each cycle. The 2020s is unlikely to be an exception.

In the 1990s, speculative tech stocks were the top performers as the spectacular Dot-Com Bubble inflated. In the 2000s, it was all about stocks linked to the ‘Chimerica’ nexus (Chinese manufacturers + EM commodity producers, with US housing and consumer stocks as the flip side of the coin). In the 2010s, the world experienced a deflationary boom that favoured large ‘dominator’ tech stocks (especially in the US) and private investments (including speculative Venture Capital).

What comes next?

Currently the world is facing an enormous deflationary shock as a result of our response to the coronavirus pandemic. During such a period, one would typically expect stocks to fall and bonds to rally, and the greenback to be ‘squeezed’ higher as companies and countries rush to pay down their US Dollar debt. We saw the first stage of deflationary shock in March. While government and central bank action have helped to stem the bleeding for now, there will probably be more pain to suffer at some point this year or next.

But when we pull through to the other side of this crisis, what sort of world will we live in? What investments might perform well in the 2020s? This is of course a vast topic of discussion. Nevertheless, we will lay out a brief draft of our current working thesis in the few remaining paragraphs of this letter.

In the coming decade, we expect western governments to play a much larger role in society, as they embrace overwhelming fiscal and monetary intervention, adopt more intrusive surveillance measures, and pursue wealth redistribution policies – the first steps on Hayek’s ‘Road to Serfdom’.

These interventionist policies will be funded by higher taxes. Central banks will engage in the monetisation of fiscal deficits (with dubious academic justification provided by MMT or other similar theories). International supply chains – already strained by the US-China Trade War – will retrench further; the world will become less globalised. Low interest rates last decade and in the near term (real and nominal) will mean that capital continues to be misallocated; productivity will remain low.

The combined impact of these changes will be inflationary, or rather, stagflationary.8

The investor playbook for the 2020s will thus probably be more similar to the 1970s than any other period: avoid bonds (other than inflation-protected securities, as interest rates rise to combat inflation); long commodities (especially precious metals); and buy only those stocks which have sufficient pricing power in an inflationary and politically fraught environment.

US Dollar-denominated assets were major winners in the last cycle, but this might not continue in the 2020s. It would be unwise to estimate just how much the inept US response to COVID-19 has adversely affected the country’s reputation for leadership and policy competence. Even though the greenback is still the world’s reserve currency, the mind-boggling size of the US fiscal deficit, the extent of the Fed’s interference in the economy, and the US government’s aggressive use of international sanctions will likely give foreign investors pause before they reach for their chequebooks.

US equities may also struggle as companies are forced to pay higher wages and tax bills, and as buybacks come under pressure. Many EM nations have been hit particularly hard by COVID-19 and may even face debt default. Even after the crisis is over, they may only see a slow recovery as they have limited fiscal firepower.

On the other hand, the advantages of fiscally conservative countries which also have competent policymakers and socially cohesive populations (as demonstrated during the recent virus crisis) have become increasingly clear, e.g., Switzerland, Singapore and even Taiwan. Such nations seem more likely to prosper.

Areas of thematic interest in global equity markets might include: health tech and surveillance (as mankind’s collective tech privacy concerns are swept away by the virus); green energy and climate change (beneficiaries of forthcoming ‘Green New Deal’ stimulus packages); and perhaps also space, the final frontier (as we all dream of escaping the emergent dystopia on planet earth).

Future missives will no doubt delve into some of these important topics in more detail, but for now, this letter is long enough.

We wish all of you and your families the best of health in this challenging time. Most importantly – stay safe!

Thank you for reading.

Andrew Limond

The original source material has been edited for spelling, punctuation, grammar and clarity. Photographs, illustrations, diagrams and references have been updated to ensure relevance. Copies of the original quarterly letter source material are available to investors on request.

The latest statistics can be found at the Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center. In reality, the numbers are likely to be far higher given limited global testing capacity (including the US) and a problem with false negatives.

In the US, there have been some suggestions that the size of the increase in unemployment benefits is so large that it may incentivise people to pocket the cash and not work, thus further boosting unemployment numbers.

This is effectively the policy which is currently being pursued by Sweden.

For now, the likelihood of negative interest rates policy (‘NIRP’) in the US seems low. NIRP has been introduced in Europe and Japan, but has been losing credibility given unintended consequences (including the impact on savers, as well as banks and other financial institutions). Rather, it seems more likely that the Fed will eventually seek to introduce yield curve control, which is apparently already being discussed within the Fed. Globally, we think that the temptation to introduce digital cash will be hard to resist, starting with China.

See, for instance, the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q4 2019 and the following Seraya Insight: ‘Four Big Picture Predictions for the 2020s’.

‘Tyranny of the Status Quo’ (1984) by Milton and Rose Friedman.

We explored many of these issues, including stagflation, in the most recent Panah quarterly letter to investors for Q4 2019 (pp.12-14) and the following Seraya Insight: ‘Four Big Picture Predictions for the 2020s’.