Two Case Studies: a Japanese 'Deep Value' Investment & a Thai 'Special Sit' Turnaround Opportunity

A closer look at two of Panah's investments: a Japanese real estate company and a Thai electronics manufacturer

This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

This Insight is an extract adapted from the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q3 2015. 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Case Study: Japanese Real Estate Company (Current Market Cap US $1.05bn)

Our first example is the fourth-largest apartment construction company in Japan, established in 1974. The company builds apartment blocks for investors who already own plots of land, and then maintains and services the apartment blocks once it has built them.

The firm’s business model is enviable, as customers must make a significant down payment, yet it only has to pay its own suppliers several months later and so operates with a negative cash conversion cycle of ~30 days. Demand is primarily driven by individuals looking for a tax break (putting up an apartment block on land allows individuals to reduce the assessed value of the property for inheritance tax by 50-80%).

The company churns out steady amounts of free cash flow each year, and this looks set to increase during the next three to four years given favourable demographic trends (i.e., more baby-boomers retiring) and because of a recent change to inheritance tax law on 1 Jan 2015 (which extended the tax to more people and at higher rates).

We estimate that revenue growth in the mid-teens seems likely for the next few years, with perhaps some risk of pressure on operating margins if the Japanese Yen continues to depreciate, although management is taking measures to reduce procurement costs. The company’s historic book-value-per-share growth (adjusted to reinvest dividends) over the last decade has been in the mid-teens, which is fairly respectable in a country which has seen very little in the way of nominal GDP growth over the same period.

We first found the company near the top of our valuation screens in late 2014 following a sell-off in the stock price over the previous 18 months. We were moved to investigate the company as a priority because of our thematic interest in the impact of inheritance tax changes. Valuations were extremely low: in January 2015, cash accounted for ~55% of market cap (even after conservatively trimming the company’s cash-pile by half to adjust for short-term payables to contractors and deposits from tenants), and the company also had a trailing free cash flow yield of slightly more than 35%. In simple terms, if an investor were able to buy the entire company in early 2015, the entire acquisition price would likely have been paid back from cash flow within three years.

This opportunity appeared to exist because the company had no sell-side analyst coverage at the time we first found it. This was in contrast to its largest competitor, with an analogous business model but ‘market darling’ status (11 analysts covering, nine of which had ‘buy’ ratings). Indeed, this stock traded at a valuation level approximately three times higher than our target company.

The standard risks for a company operating in the Japanese real estate sector apply to this company: demand for real estate; construction material costs (and the effect of a weak Yen); labour costs (construction workers are scarce); earthquakes; a sudden rise in interest rates; regulatory changes, etc. Given the low valuation of the company, however, we felt that these risks were already priced in and that there was an adequate margin of safety.

A larger risk factor made us pause for thought, however, and this was the company’s large off-balance sheet liability. The company’s policy is to guarantee a rental occupancy rate of 91% for clients for around ten years (similar to the yield guarantee which its competitor offers). This creates a large risk as the company would theoretically be on the hook if vacancy rates were to rise.

It is reassuring, however, that this has never happened during the company’s history, with the highest vacancy rate in recent times being ~5% in the wake of the Great Financial Crisis of 2008. It was our judgment that even in another financial crisis, it would be unlikely that the company would be liable for any more than a fraction of this off-balance sheet liability. Moreover, the company has a long operating history and an enormous nationwide apartment database, so has historically been able to avoid neighbourhoods at risk of falling rents.

We also noted that the markets had chosen to ignore the competitor’s similar large off-balance sheet liability when assigning a valuation. We thought that investors might start to get more interested in our target company as its operating performance improved, and if the conservative founding family (still the dominant shareholders) would acquiesce to raise the dividend yield.

We started researching this company in December 2014, and the first conference call with management was at the start of January 2015. After some additional research, we initiated a small position in the company early in same month. In early March, we visited the company on site in Nagoya, and made a point of also visiting the #1 competitor (in Tokyo), as well as ten other companies operating in a similar area.

These visits helped build confidence in our investment thesis, and so we increased our position shortly thereafter (thus making the company one of the fund’s top holdings). We considered increasing the position size to make this a high conviction holding of even larger size, but two factors prevented us:

It seemed imprudent to make this position too large given the company’s still significant off-balance sheet liability; and,

The fund had portfolio exposure to other real estate companies in Japan, and we wanted to avoid over-concentration in one sector.

After a ~+75% rise in the share price from January to mid-August, we decided to trim the holding, taking profits while we waited for operating results to confirm our thesis. First quarter results announced in early September were stronger than we had expected, reflecting strong sales and good cost controls. We then added to our holding slightly, and the stock price moved higher. The stock has risen +93% from the start of the year to end-September, but still looks fairly cheap.

Case Study: Thai Electronics Manufacturing Company (Current Market Cap US $914mn)

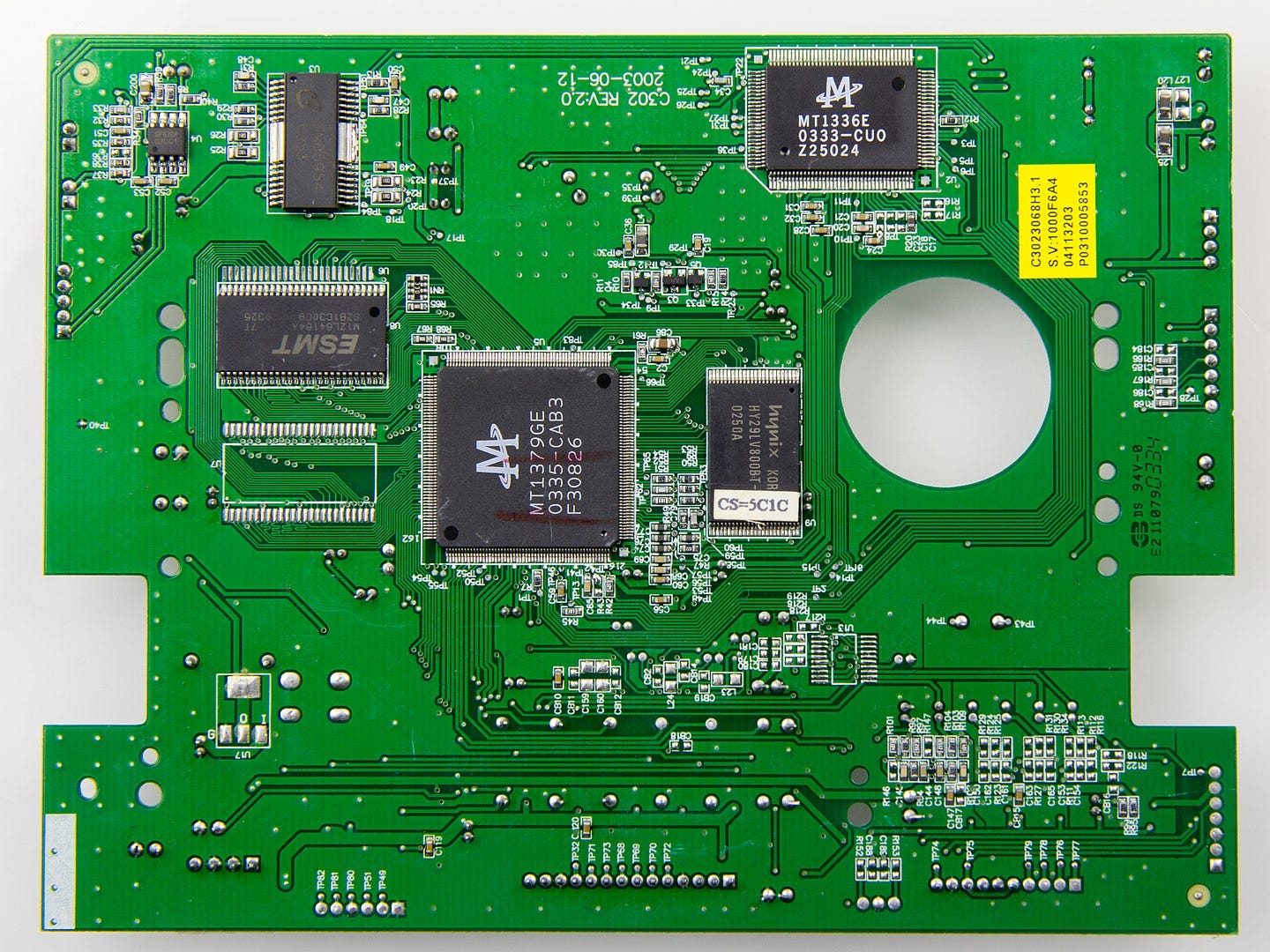

Our second example is the world’s #5 maker of Printed Circuit Boards (PCBs) for the automotive industry, a Thai company founded in 1983.

More than 70% of the company’s customers are in the auto industry: Continental is the largest customer with ~22% of sales, followed by Robert Bosch with 12%, Valeo with 7%, and Autoliv with 3-4%. The total market size for automobile PCBs in 2014 was US $3.86bn, with current underlying growth of 5-6%. The automotive PCB production process is more demanding than for consumer electronic PCBs, as the defect rate has to be kept lower. It typically takes years for a PCB-maker to be approved by an auto company, so the barriers-to-entry are also high.

The major industry players are a Japanese company with 15% market share (in 2013), a US company with 13% share, another Japanese firm with 10%, a Taiwanese company with 9%, and finally our Thai target company with 7%. The top five thus account for ~47% of the market. Quality is similar across the top five, but pricing for the Japanese companies is >30% higher than the lowest-cost Thai producer, the US company price ~10% higher than the Thai competitor, and the Taiwanese company has ~3% higher prices. Unsurprisingly, the top three have been losing share to the Thai and Taiwanese ‘upstarts’. In particular, the Japanese companies have been struggling in recent years, with almost continuous operating losses despite much higher pricing.

The Thai target company’s largest factory was flooded in late 2011 (in the Great Thai Floods) and 70% of machines were destroyed. This caused massive disruption, but the good news was that the company was fully insured (including for business interruption) and could pay for a replacement factory. Moreover, the flooded factory was the least efficient plant with the highest defect rate.

The company founder gave his son (who was in his early 30s and had worked in the company since 2005, with a Computer-Engineering Degree from the University of California and an MBA from Cornell) the task of rebuilding the factory in 2012. The son had already experimented with introducing SAP in the company since 2009, but now decided to reinvent the entire production process, which typically involves more than 3,000 parts and 40 steps (many of which have to be repeated several times).

The traditional production process (and the way the competitors still work) involves flow diagrams on a blackboard, with division of work into five clusters; workers carry materials between different production lines. The son of the founder pioneered straight-line production instead, using complex computer automation. It was more complex than the previous system, but once implemented in the new factory, yields improved dramatically and the labour-to-revenue ratio halved.

We identified this stock as a potential investigation target shortly after the Panah Fund’s establishment in 2013. It had appeared on our screens because of the dramatic improvement in return-on-capital metrics from early 2013.

These improvements were as a direct result of the process changes implemented by the founder’s son, who was appointed as the new president and CEO in July 2013. He then began to implement more changes which should lead to ‘instant wins’ in terms of efficiency and profitability, including streamlining the procurement process and doing smaller upstream acquisitions (i.e., taking control of companies involved in supplying input materials). He also put a lot of effort into trying to win new customers, especially Japan automakers. Most importantly, he decided that the company should increase its scale, and so committed to an ambitious capex plan to double capacity by end-2014, thus enabling the firm to lower per-unit production costs even more while improving quality.

We met the new CEO in October 2013, and he explained the turnaround story. After working harder to understand this niche industry, we initiated a small position in late 2013.

At the time we first met the company, it seemed to us that sell-side analysts were significantly underestimating the turnaround in the company and the potential for both strong top-line growth and operating margin improvement. (12 local Thai analysts covered the stock, but they looked at other Thai electronic stocks rather than the global automotive PCB industry.) The analysts were expecting THB 9.5b in sales for 2014 with an operating profit margin of 11%, whereas we thought that sales could reach THB >11b in 2014 with a margin of closer to ~15% (in actual fact, revenues reached 11.3b and the operating profit margin hit 16.7%).

One of the things that interested us most (but also represented a large execution risk), was CEO’s plan to invest in a new factory to double the company’s capacity using the new processes. If it went well, though, we saw that there would be the potential for the company to cement its dominance as the lowest-cost producer of automobile PCBs, and thus grow revenues and increase profits through economies-of-scale in the coming years. On our numbers, we would only be paying a forward PE ratio of 7x for growth of ~20% and a ROIC which would have risen from an average ~1% to the high-teens level in just two years. Sharp gains in the stock price into early 2014 prompted us to trim the size of the position, but we added again later in 2014 (at slightly higher levels) once we had more conviction that the new factory roll-out was going to plan.

The investment was not without risks… Clearly this was a cyclical stock with high exposure to global automobile sales, mitigated in part certain degree by the secular increase in penetration of electronics for cars. The company also had high debt levels when we first met, apparently with a gross leverage ratio of 2.3x and net leverage ratio of 1.8x (according to the investment presentation). However, once we adjusted for insurance claims due and non-debt liabilities, the net gearing ratio fell to 110% at end-2013 (and we guessed it would fall to <90% by the end of 2014, even with increased capex on the new factory). It seemed fairly certain, even using conservative numbers, that the company would not have any problem in covering interest payments.

The execution risk on the introduction of the new factory concerned us the most, together with the potential pushback from customers on pricing for bulk orders (as the new capacity came on-line). Unsurprisingly, this was also the new CEO’s number one concern. There were other risks, e.g., forex (75% of sales in USD and 24% in EUR) as well as raw material costs (copper, gold, tin), but we judged that these were manageable. In fact, it even seemed possible that forex and commodity prices might move in the company’s favour.

Since first buying the stock in October 2013, the stock price has increased by +215% (to end-September 2015). We chose to trim the position in early October 2015 following news that Volkswagen had falsified emissions reading for its diesel cars (we estimate that the company has <8% exposure to VW, and <50% to European automakers).

We remain confident about the company’s strategy future development and successful creation of a fairly durable ‘moat’ (i.e., as lowest-cost producer, and based on technological innovations in the PCB production process). After the strong rally, however, we see current valuations as fair. We would also like to see what impact the diesel scandal has on the company’s European customers before taking any further decisions.

Thank you for reading.

Andrew Limond