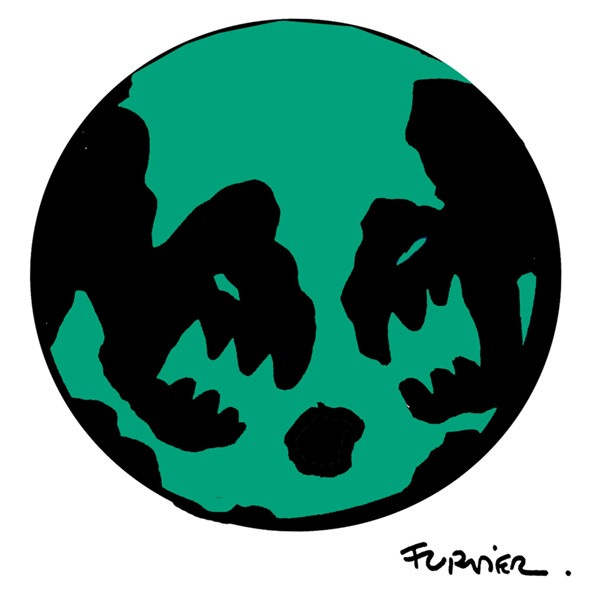

Towards a More Fragmented World

The inexorable drift towards a more 'multipolar' world and the implications for Asian investment

This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

This Insight is an extract adapted from the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q3 2018.1

This year has not been kind to the typical Asian investor. Like a child who has wandered into his parents’ bedroom at just the wrong moment, the experiences of 2018 have been confusing, traumatic, and somehow difficult to ‘un-see’.

While it might take quite some time for the ultimate consequences of the year’s events to come to fruition, we have little doubt that history will look back on 2018 as a turning-point: the year when the liberal post-war consensus was cut adrift, and investors lost their innocence.

In coming years and future letters, we will no doubt have to grapple with the implications of these developments, but in the meantime, here are some of the bigger issues we are contemplating now:

China is under pressure. US trade sanctions are forcing a rethink of the country’s development strategy. Fiscal constraints are tighter; the authorities have less room to stimulate the economy given the bad debts created by previous stimulus episodes. Interest rates are already low. Growth is being supported by pushing households to take on more debt (particularly mortgages). Will this allow China to muddle through for one more cycle? Probably, although a rebound on the scale of 2016-2017 seems unlikely. China will have to double down on attempts to win allies in Europe and Asia, but it would be well-advised to rethink its soft power initiatives.

There has been a bear market rally for the US Dollar in 2018, but the longer-term picture for the greenback looks less constructive. The price to pay for President Trump’s late cycle stimulus will be higher budget deficits in years to come. Meanwhile, trade tensions are alienating most potential future large-scale buyers of US bonds. Higher rates will be the most likely result, which might eventually create a problem given elevated debt levels.

The hegemony of the US Dollar seems assured for now, but cracks are starting to appear as the current US regime aggravates allies and rivals alike. For example, renewed sanctions on Iran have prompted Europe, Russia and China to search for alternative payment methods to bypass US banks. President Trump seems to be intent on shrinking the US trade deficit, though in fact a structural current account deficit is a prerequisite for a reserve currency, as this allows dollars to flow abroad (which are in turn recycled back into its bond market).

No other currency is suitable for global reserve currency status, yet. The Euro remains a flawed currency so long as northern European countries refuse to extend fiscal guarantees to the south. China’s current account might well slip into deficit in coming years, Renminbi trade is being promoted, and CNY bond issuance is set to increase. All of these appear to lay the ground for potential future reserve status.2 Yet the Renminbi itself represents uncertain value given massive monetary stimulus over the last decade, and without China’s strict capital controls there would be a high risk of crippling capital flight.

President Trump is keen to boost US manufacturing. He may well be correct that a healthy domestic manufacturing sector makes for a healthier domestic economy and society. It will be difficult, however, to ‘re-shore’ supply chains to the US given the large amount of intangible knowledge that has been lost over decades as manufacturing has moved abroad.

Instead, over time, US sanctions will probably lead to a fragmentation of the globalised trading system. An Asian trade zone will likely develop with China at its centre, with manufacturing supply chains which are extended into SE Asia as China starts to offshore manufacturing of household appliances, tyres, communications and computing equipment, as well as semi-conductors.3 The same SE Asian nations (e.g., Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Malaysia) might well also be able boost their presence in the US-centric supply chain, possibly making them the biggest beneficiaries of US trade policy as China is blocked. Larger Asian economies such as Japan and Korea will have to walk a fine line as they balance competing demands from the two rival powers on opposite sides of the Pacific.

Although the exact shape of the world-to-come seems more blurred than ever, these observations suggest that in five years we will all be living in a more ‘multi-polar’ world than today.

The scale of the challenges to the current status quo – in terms of geopolitics, economics and investment – should not be underestimated. As a result, we think that the risk of a recession in the near-term has risen (particularly if there is no de-escalation in trade tensions).

The monetary and fiscal response to the next recession will be challenging, given already-elevated government debt levels, the continued prevalence of ongoing ‘unconventional’ monetary policy among major central banks, and increasing social pressures.

No matter what path this journey will take, investors will have no choice but to adjust – volatility begets opportunity.

Thank you for reading.

Andrew Limond

The original source material has been edited for spelling, punctuation, grammar and clarity. Photographs, illustrations, diagrams and references have been updated to ensure relevance. Copies of the original quarterly letter source material are available to investors on request.

Hence China’s ‘One Belt, One Road’ initiative, and the launch of the Chinese Yuan-denominated crude oil futures contract in March 2018.

These are the Chinese sectors with a strong overseas revenue mix. For more information, see TS Lombard’s ‘Tariff Evasion Primer’, 27 Sept 2018.