The Pandemic & Asian Trade Developments

How the 'goods over services' pandemic dynamic has created winners and losers in Asia

This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

This Insight is an extract adapted from the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q1 2021.1

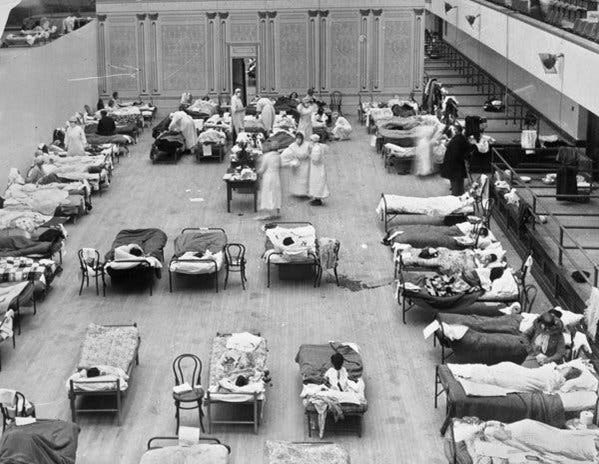

Earlier in the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, we made the observation that historically, most pandemics have lasted for at least two years and have often come in multiple waves. As distressing as the Covid-19 plague has been, in this respect the development of the disease has so far proceeded in line with historical precedent.

In previous letters, we also noted that while the aftermath of wars is usually inflationary (prices rise as the non-military productive capacity of warring states has been destroyed and the labour force decimated), the impact of major historic pandemics has tended to be deflationary. This is because a plague-driven population decline weighs on aggregate demand, even as the productive capacity of the economy remains at pre-pandemic levels.

In this regard, the current pandemic has been very different. By now, everybody seems to know somebody who has been touched by the virus. Every death is tragic, and the social and political implications of SARS-CoV-2 have been and continue to be enormous. Given how large pandemic looms in all our lives, however, it is sobering to think that the demographic impact of Covid-19 has so far been modest compared to other major historical pandemics.2

Rather than major population declines, the largest adverse economic impact of the Covid-19 epidemic has come from the political decision in many countries around the world to implement historically unprecedented ‘lockdowns’. Such restrictive policies would not have been technologically feasible in previous pandemics, but they have been adopted with alacrity in 2020-21.

Locking down entire populations and economies carries with it the risk of an enormous deflationary shock, especially in a world so dependent on debt. The market panic of March 2020 was rational insofar as there was an increased danger of a very adverse outcome for the global economy – maybe even a depression.

More than one year on, it is clear that this nightmare scenario has not come to pass. While there are pockets of deflationary stress (e.g., in commercial real estate, as well as in service sectors such as hospitality, travel and retail), household balance sheets in the Developed World are in rude health, and markets have staged an extraordinary recovery. Equity markets in the US and many other countries are near all-time highs, and credit spreads at record lows.

The reason for such an extraordinary ‘positive outcome’ is of course the unprecedented monetary and fiscal stimulus deployed over the last year in most of the world, and especially the West. While this has led to much handwringing over the unsustainability of fiscal deficits and concerns over currency devaluation, many economies have nevertheless managed to stage a robust recovery as governments have forced a rebound in the industrial cycle. Asset prices have thus managed to shrug off worries and push higher on a wave of liquidity.

Given changing patterns of demand (e.g., goods over services) as well as supply constraints imposed by lockdowns and other pandemic policies, certain areas of the global economy have even experienced significant supply shortages and pricing surges. One key example of such pricing pressure is the massive increase in freight rates for shipping containers from China to the US. (This was as China suppressed its own Covid-19 outbreak at an early stage, while the US experienced a later viral surge which constrained movement even as the government sent stimulus cheques to every household.)

Here in Asia, there seem to have been various second order effects as a result of the differing response to the pandemic around the world. Below, we highlight some new developments in trade patterns, as these are perhaps not attracting as much attention as they deserve amid the market mania.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Asian Trade Developments

Regular readers are probably already familiar with our view that robust export manufacturing growth has been the foundation on which the Asian economic miracle has been built.3 Exports provide foreign currency revenues which are reinvested at home, underpinning technological development and consumption, and thereby driving a virtuous cycle.

Given the dramatic events of the last year, it would be remiss for us not to mention the latest developments in Asian trade.

Demand for goods of all sorts rebounded in H2 2020 on the back of massive stimulus programs in the West and smaller programs elsewhere. With economies locked down, consumers could not spend much of this money on services such as travel and restaurants. Instead, there was an explosion in online purchases of ‘stuff’.

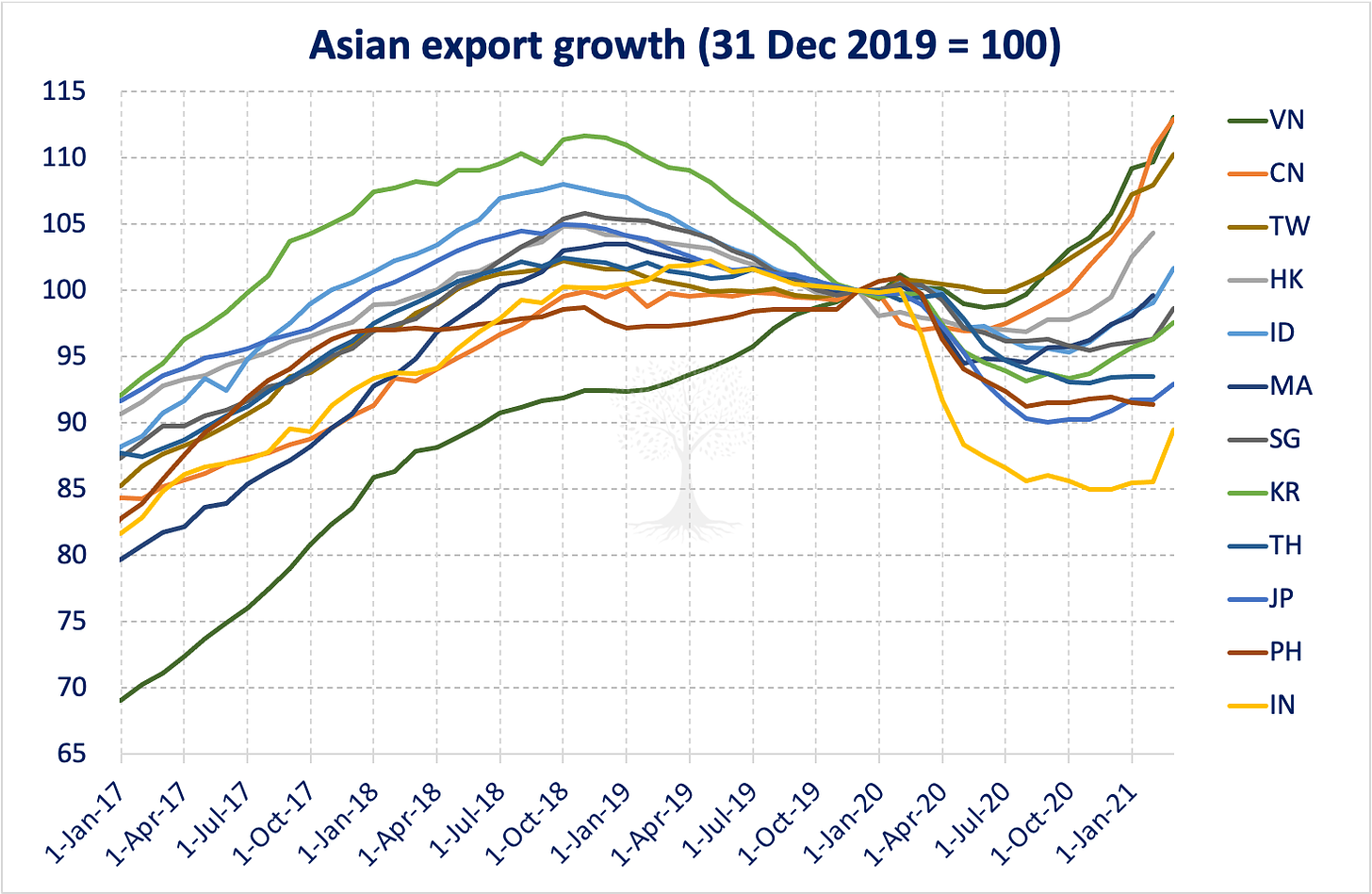

It is not the case, however, that all exporters have benefitted equally from this shift in demand. A massive gap has opened up between the majority of countries which have struggled with the virus, and a handful of nations which managed to get the pandemic under control early, thus allowing their factories to reopen quickly and service the rebound in demand.

China & North Asia

In US Dollar terms, China has been by far the largest ‘export boom beneficiary’ of the last year, with exports now growing in the mid-teens year-on-year even as imports have flatlined (Figure 3). As a result, China’s current account surplus approached ~2% in 2020. This is respectable performance from the world’s second largest economy, which as recently as 2019 was thought to be moving towards a structural current account deficit.

Even as the CCP has been attempting to persuade investors that China’s growth mix is pivoting towards a ‘dual circulation’ economic model (i.e., more dependent on imports and consumption), exports have surged to boost growth. Indeed, it was probably China’s strong export performance which gave the Chinese authorities sufficient confidence to rein in stimulus and credit growth from late 2020.

An almost complete halt in China’s outbound tourism has also been a major contributor to the renewed strength in China’s balance of payments, which has in turn helped to support the Renminbi. As Chinese tourists resume their globe-trotting and foreign shopping trips (perhaps from early 2022), there is a risk that China’s current account will come under pressure again.

As the world recovers from the pandemic, it is also uncertain whether China will be able to maintain the export market share that it has gained over the last year. The export ‘losers’ of 2020 have for the most part been developed nations (particularly in North America and Europe). As the pandemic subsides, we expect them to question Chinese trade practices alongside national security issues. This is something for investors to monitor as the year progresses, but for now China’s export orders remain strong.

Given the strength in China’s exports and current account, it is perhaps surprising to see that China’s forex reserves have barely grown over the last year.4 It is possible that reserves are growing outside the official channels,5 but we would also note that negative ‘errors and omissions’ in the balance of payments (a proxy for capital outflows) have risen sharply. Indeed, even as the balance of payments is in surplus, these ‘outflows’ have been running at similar levels to 2015, a time when investors were panicking over capital flight from China.

In contrast, the 2020-21 ‘China story’ has focused on foreign inflows to the bond market as China adopts more ‘conventional’ monetary and fiscal policy than Western nations, helping to support the Renminbi even as bond yields remain above 3%. The tentative conclusion we draw, is that even as foreigners rush to buy Chinese goods and Chinese government bonds, in contrast Chinese banks, corporations and individuals seem keen to diversify their savings abroad.

How does China’s 2020 export story compare to other Asian countries? Technology-oriented Taiwan has put in a very respectable export performance over the last year, enjoying mid-teens growth (Figure 3). Korean tech exports also did well, although the country’s aggregate export performance was dragged down by weakness in petrochemicals, heavy industrials and autos.

South & Southeast Asia

The Asian export losers of the last year are for the most part located in South and Southeast Asia, including India, the Philippines and Thailand. These countries were markedly less successful in controlling the virus and keeping their export industries humming (Figure 3). Indonesia and Malaysia also came under pressure, although they have rebounded faster than peers thanks to the higher proportion of commodities in their respective export mixes.

Remarkably, most of these nations also saw a marked improvement in their current account balance in 2020, helping to support their currencies. This was on the back of a large contraction in domestic demand which led to a collapse in imports.

India and Indonesia, which usually suffer from chronic deficits, saw their current accounts rebound towards positive territory. The Philippines went from a deficit to a comfortable surplus. Malaysia also improved its surplus position. Only Thailand saw its current account surplus halve as the country’s heavy dependence on tourism took a large toll.

As the domestic economies of these countries rebound in 2021-22, it will be interesting to see whether they will also be able to regain export share. This will be necessary to mitigate downward pressure on local currencies, and relative interest rate levels will also no doubt play an important role in these forex markets.

Vietnam

The major exception to the South and Southeast Asian export weakness story, has of course been Panah’s ‘favourite market’: Vietnam. Given the country’s large export exposure (with an export-to-GDP ratio in excess of 100% even before the pandemic),6 in early 2020 we became concerned that any major downturn in global trade – perhaps triggered by the pandemic – would have the potential to affect Vietnam quite badly.7

In reality, the opposite happened as Vietnam gained massive export market share in 2020 (Figure 3). The authorities did a remarkably good job of keeping the virus in check despite fewer resources than its neighbours. Covid-19 case numbers stayed low and factories remained open.

Many multinationals were already looking to diversify their production base towards Vietnam before Covid-19 arrived on the scene, and the pandemic seems to have reinforced this trend. As a result, Vietnam’s export growth – which was already surging before the pandemic – has been nothing short of extraordinary. Vietnamese exports have doubled in dollar-terms since 2014, with mid-teens growth over the last 12 months. This is a much better outcome than might have reasonably been expected a year ago.

Blockbuster export revenues have put the Vietnamese economy on a firmer footing. Corporate earnings and balance sheets have been strengthened, and Vietnamese industry is rapidly moving up the value chain.

Vietnam also continued to grow its forex reserves at a rapid clip in 2020 as the authorities intervened to keep the Dong competitive. As the global pandemic subsides, we expect such currency practices to come under increasing scrutiny from the US and Europe. This probably means that Vietnam will have to allow its currency to appreciate over time – similar to the Renminbi from 2005 – which should also help provide a tailwind to Vietnamese equity returns for foreign investors.

We also think that it might become increasingly difficult for the Vietnamese authorities to sterilise all inflows. This might mean some overflow into domestic credit growth. Loan growth has been more constrained in recent years, which has meant that asset prices (housing prices and the equity markets alike) have not fully reflected the massive strides taken by the Vietnamese economy in recent years.

Foreign investors have been net sellers of Vietnamese equity market over the last year, along with most other Asian markets (except China). In Vietnam, it has been local investors who have driven stocks higher. We expect foreigners to return, as valuations in Vietnam remain reasonable and the growth outlook is attractive, in sharp contrast to elsewhere in the world!

Thank you for reading.

Andrew Limond

The original source material has been edited for spelling, punctuation, grammar and clarity. Photographs, illustrations, diagrams and references have been updated to ensure relevance. Copies of the original quarterly letter source material are available to investors on request.

An innovative graphic from the Visual Capitalist helps to visualise the scale of Covid-19 relative to historic pandemics. The ‘Spanish Flu’ (1918-19) was the deadliest virus of the last century in absolute and relative terms with an estimated 40-50mn deaths, while the slow-burning HIV/AIDS epidemic (1981-present) has claimed an estimated 25-35mn lives. Johns Hopkins estimates that so far, more than 3.1m people have died with Covid-19, a death toll which represents ~0.04% of the global population. This represents a similar proportion to those who died from the Asian Flu (1957-58, ~1.1mn deaths) and the Hong Kong Flu (1968-70, ~1mn deaths). With Covid-19, the largest impact has so far fallen disproportionately on the elderly and those with comorbidities. While much about the virus is still unknown and new strains still present a risk (and the latest developments in India are of concern), rapid vaccine development and deployment appears to have mitigated a worst-case global scenario.

For more information on the importance of the export growth model, see the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q2 2019 and the following Seraya Insight: ‘Why invest in Asia? A Fundamental Look at the Drivers of Growth and Stock Returns in Asia since 1960’. This draws on analysis from Emerging Advisors Group.

Taking into account valuation and forex effects, China’s foreign exchange reserves probably declined slightly.

Chinese reserves might be growing outside the official channels as Chinese banks increase their US Dollar holdings, a form of ‘quasi-official’ currency intervention.

See the Panah Fund quarterly letter to investors for Q2 2019 and the following Seraya Insight: ‘Why invest in Asia? A Fundamental Look at the Drivers of Growth and Stock Returns in Asia since 1960’.