This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

This Insight is an extract adapted from the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q3 2024.1

The great China rally of late September – still underway – may well become one of the great ‘positioning unwinds’ of the decade.

On 24 September, the Chinese authorities convened a rare combined press conference involving China's central bank, top securities regulator and financial regulator. Thus assembled, they proceeded to announce a slew of monetary and other stimulus measures.

This unexpected show of force was enough to persuade investors that the Chinese authorities were finally getting serious about placing a floor under growth, and perhaps even stimulating the economy after years of moribund growth.

Equity markets in China and Hong Kong spiked violently in response, and over the last two weeks have made strong gains of +20-30%. Amid the excitement, however, it is important not to lose sight of exactly what policies have been announced and just how much remains to be done.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The New Stimulus Measures Placed in Context

The most impressive aspect of the press conference was undoubtedly the theatre surrounding the event, so as to give a strong impression of a coordinated policy response. The actual measures announced were as follows:

A cut in the policy rate (i.e., the seven-day reverse repo rate) by 20bps to 1.5% (larger than the usual 10bp rate cut increment);

A 0.5% cut in the reserve requirement ratio (‘RRR’), expected to provide CNY ~1tr in liquidity;

Housing market measures, including mortgage rate cuts for existing home loans, a reduction in the minimum downpayment for second homes from 25% to 15%, and increased central bank funding for the affordable housing relending facility; and,

Support for the stock market (worth an estimated CNY ~800bn), in the form of a central bank asset collateralisation swap program to provide liquidity for financial counterparts to buy equities, and a relending facility for banks so they can provide funding to companies to undertake buybacks and share purchases.

Whether considered in isolation or in combination, these measures do not really break new ground. The rate cuts announced are incremental rather than dramatic. After all, the policy rate has already been cut by more than 2% over the last four years, and the RRR by 3%.

There have already been several rounds of relaxation in the housing market in the last two years. The most recent CNY ~300bn package came in May of this year,2 and was described as ‘historic’ at the time. In reality, however, it has fallen short of expectations.3

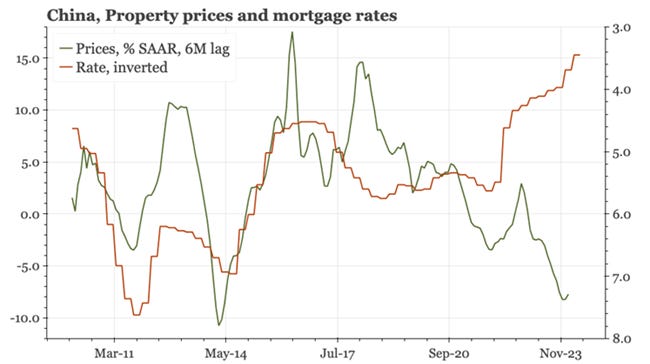

Indeed, despite various monetary and real estate-focused stimulus measures over the last four years, construction activity has fallen, real estate prices have declined (Figure 2), and economic growth has ground to a halt (Figure 4).4

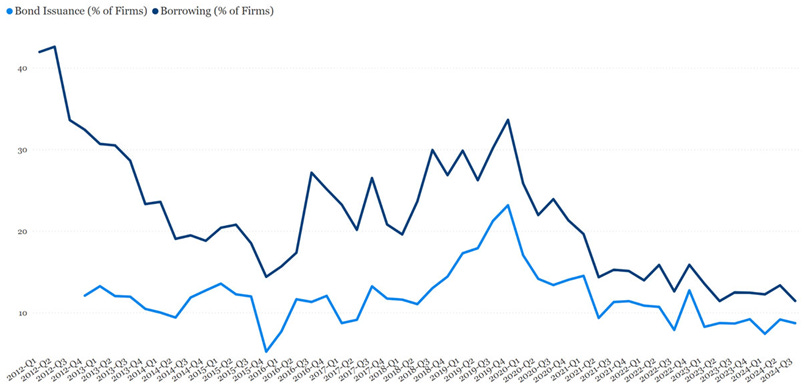

The problem has not been the availability of credit or the price of credit, but rather that there is little demand for credit (Figure 3). In other words, even as the authorities have loosened monetary policy, they have been pushing on a string.

The Stock Market Reaction

Why then have equity markets in China and Hong Kong rallied so hard in response to the latest measures?

Part of the excitement around the rally is because the authorities seem to be keen to promote the stock market (i.e., the measures in point four above). This took investors by surprise – just a couple of weeks previously, the authorities had been arresting investment bankers and slashing finance sector salaries.

It is notable, however, that few details of the stock market support programs are yet available. Indeed, if no further information is released in the coming weeks, then that would likely undermine confidence in the rally. It is also possible that the already-massive scale of the stock surge might make it less likely that any official market support will be forthcoming.

Another key reason for the massive market rally is that after more than three years of market underperformance and divestment pressure, most investors are underweight Chinese assets. With extreme positioning, even a slight change in sentiment is enough to trigger a large rally, especially with valuations at such ‘cheap’ levels, at least relative to history.5

The final point is that some investors seem to believe that the 24 September press conference was tantamount to a ‘policy U-turn’ on a similar scale to China’s ‘Zero Covid’ reversal in December 2022. In other words, policymakers have supposedly fired the starting gun on what will likely be a far broader range of fiscal stimulus measures.

The media’s ‘whisper numbers’ are for a further CNY ~2tr in special bond issuance (~1.5% of GDP) to support a consumer stimulus and to help local governments tackle debt problems.6 Some investment banks are upping the ante and are guiding for an even larger stimulus package.

What About More Fiscal Stimulus?

Given centralised control of the economy and political system, China is the one place in the world where it should be easy to implement combined monetary and fiscal stimulus. It is thus curious that this has not already happened.

It was widely expected that an announcement would come with a fanfare to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China (‘PRC’) on 1 October. But no news came during the holiday week.

Some are now expecting the stimulus to be announced at the NPC Standing Committee meeting in late October. Others are saying that there might be even more stimulus measures announced at the upcoming Politburo meeting and the Central Economic Work Conference in December.

The risk is that the equity markets have already moved to price in a significant stimulus package, and that reality disappoints. This is not an idle concern. After all, Chinese president Xi Jinping is known to be sceptical of consumer stimulus measures and massive fiscal packages due to the unwanted side effects that such policies can bring.

President Xi instead prefers to aim for ‘common prosperity’, and has set technological advancement and self-sufficiency as key policy goals. Indeed, his celebratory speech for the 75th anniversary of the PRC on 30 September focused on issues other than the stimulus.

The other key question is that even if a significant fiscal stimulus package of CNY 1-2tr is announced in the coming weeks, would this be sufficient to turn the Chinese economy around?

The scale of the challenge is much larger than this. It will cost much more than this to tackle bad debt in the real estate sector and lay the foundations for future growth. Other areas of the economy also require significant structural reforms. Such actions would necessitate a correct diagnosis of the nature of the challenge, and then the time and willpower to implement structural reforms. This is politically unpalatable. In any case, current priorities appear to lie elsewhere.

The State of the Economy & What Are Markets Pricing?

The latest economic data in China has been weak. Construction activity, industrial profits, employment, and prices are all in retreat. While the Chinese economy might be growing at ~+5% in real terms, nominal GDP peaked in mid-2022 and has since flatlined (Figure 4). Note that it is nominal growth, not real growth, which matters most for revenues, profits and wages.

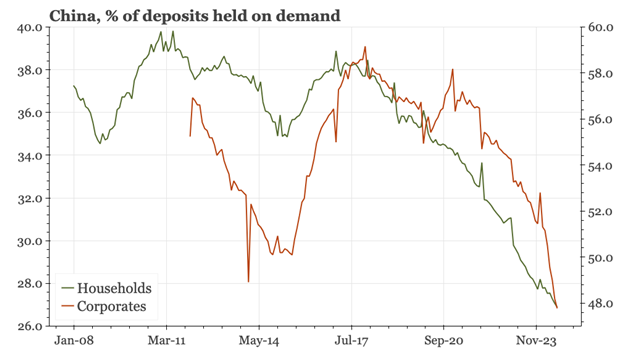

There is a deflationary mindset in China right now, and domestic investors have responded to weak growth as one might expect – by piling into long-dated government bonds and time deposits (Figure 5). This has contributed to a decline in the velocity of money.

For equity markets, this might not matter much. Given the scale of under-positioning in China, as well as the ongoing media and broker excitement surrounding the change in tone from policymakers, the path of least resistance for stocks might well be higher in the near term.

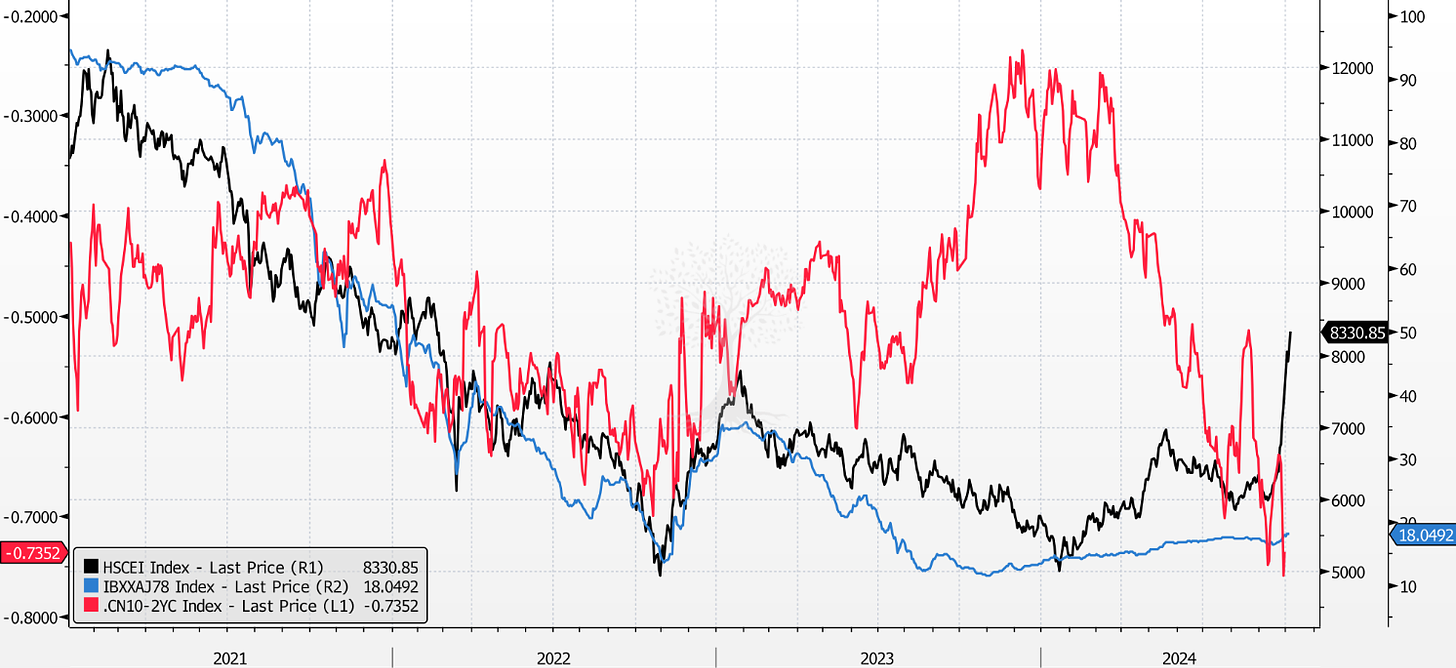

It is notable, however, that moves in other asset prices – such as real estate debt and the onshore yield curve – have been much more modest than the move in equities. These indicators do not yet reveal any real hopes of reflation (Figure 6).

What would it take for us to get more optimistic on the fundamental economic outlook in China? Of course, a modest fiscal stimulus might be good enough to push equities higher over a short-term time horizon. The risk, however, would then be that this ‘sugar high’ fades in 2025.

To see a real structural inflection point in the economy, we believe it is necessary to see a much larger package of reforms which tackle the country’s ‘four D’ structural issues: Debt, Demographics, a lack of Demand and US-China Decoupling. These issues do not appear to be front of mind for policymakers at the present time.

In the meantime, we will be watching the following indicators for clues as to whether a cyclical economic recovery is gaining traction: a steepening yield curve; a stronger rally in real estate debt; a fall in time deposits at banks; and stronger base money growth.7 As and when these indicators turn around, the equity rally might be on a firmer footing.

History Rhymes…

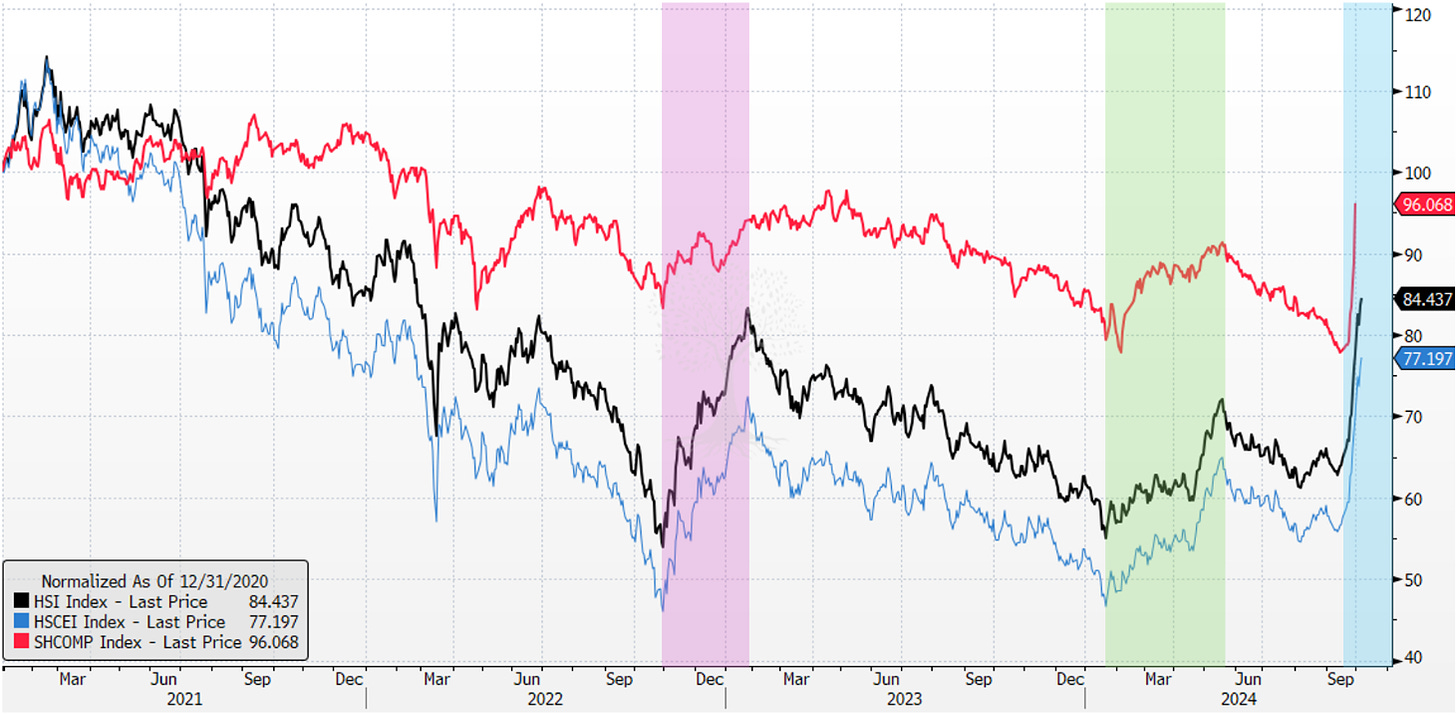

It is easy to forget that since the peak of the Chinese real estate market in mid-2021, the current rally represents the third major attempt that HK-China stock markets have made to recover their bear market losses (Figure 7). Each rally was predicated on stimulus and growth optimism.8

The first rally commenced in early Nov 2022, lasting three months in HK and longer in China (+55.5% HSI, +58.0% HSCEI, +18.2% SHCOMP; trough-to-peak), but almost all of these gains were reversed within a year.

The second rally commenced around the Lunar New Year in early 2024 and lasted around four months (+33.2% HSI, +41.3% HSCEI, +20.5% SHCOMP; trough-to-peak), with more than half of these gains reversing within a few months. That brings us to the most recent episode…

This rally has been much steeper (+26.6% HSI, +30.4% HSCEI over just two weeks; and +21.4% SHCOMP until the holiday close on 30 September). It has also started from a higher base, with much greater trading volumes than previous ‘stimulus stock rallies’. Only time will tell whether this is the rally which endures, or whether investors will once again be frustrated.

Our rough roadmap for China in the 2020s – albeit an imperfect one – is the bursting of the Japanese real estate bubble in 1990 and the ensuing ‘lost decade(s)’. Numerous attempts at reform in 1990s Japan fell flat, although the stock market managed to stage some spectacular rallies.9

Amid a total market decline of -73% from high in December 1989 to the trough in April 2003, the Topix index nevertheless managed to stage two rallies of >+50%, and many more surges of +25% or more (Figure 8). The similarity to Chinese stocks following the property peak of 2021 is uncanny.10

While it might have been possible to trade these rallies, the key thing was to realise that one was in a bear market. After all, bear market rallies are always better than the real thing!

Investors should bear this history in mind before getting too carried away with the current rally. We would be wary of those who are cheerleading rather than taking a more nuanced approach. Those who are shouting the loudest, probably have something to sell.

Thank you for reading.

Andrew Limond

The original source material has been edited for spelling, punctuation, grammar and clarity. Photographs, illustrations, diagrams and references have been updated to ensure relevance. Copies of the original quarterly letter source material are available to investors on request.

Our best guess is that the latest measures will have effect of a similar quantum, although this depends on one’s assumptions. Some sell-side estimates are larger.

In May, the central government urged 200 local governments to buy unsold homes to ease oversupply (preferably to convert it to affordable housing), but few have done so. Local governments are strapped for cash, as income from land sales (always an important source of local fiscal revenues) has evaporated. Moreover, the prospective rental yield on affordable houses bought at current market prices is below the central bank’s funding rate. Local governments also seem to expect real estate prices to fall much more before stabilising (as several governments have offered to buy real estate inventory from developers at a ~-50% discount to current ‘market prices’). Local banks and SOEs are also not well-positioned to fund these purchases. Instead, direct central government funding would probably be necessary. The IMF has estimated the quantum of funding required to be worth as much as ~5.5% of GDP over four years (i.e., US $1tr) – a large multiple of the central bank’s May funding plan. Note that the IMF proposal was rejected by the Chinese authorities in August.

Peak price growth for Chinese property, as well as peak activity (i.e., residential starts), came in mid-2019, with peak prices reported in Q3 2021. By this time, however, the Chinese real estate crisis had already begun, with severe credit stress emerging from mid-2021 (Figure 6). Observers had been pointing out the disconnect between real estate fundamentals and prices for quite some time before the crisis began. Note that it was the authorities’ decisions to introduce the “three red lines” policy in 2020 and later commence a crackdown on the Evergrande group which marked the top, and catalysed the crisis.

It is unclear what the right valuation multiple for Chinese stocks should be. However, given that foreign buyers of Chinese equities are never really the legal beneficial owners of shares in a Chinese company, that political interference in private Chinese companies has surged in recent years, and that geopolitical issues and sanctions restrict certain investors’ access to the Chinese market, one would have thought that it is appropriate for the market to trade at a lower multiple than it did before the pandemic.

This compares to the famous CNY 4tr Chinese stimulus package of 2008, which at that time was equivalent to an expected ~14% of China’s annual GDP, spread over two years.

Hat-tip to PC at EAE for his sound analysis.

The October 2022 rally was also underpinned by hopes that China’s ‘Zero Covid’ policy would be suspended, and the economy reopened. This policy reversal came in December 2022.