This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

Why would a ‘quality-oriented’ investor consider investing in any company related to the commodities sector?!

Commodity-related companies are typically capital-intensive, low margin businesses with little to no pricing power. They often operate in difficult jurisdictions and are subject to a plethora of risks.

It was for good reason that Mark Twain famously defined a mine as “a hole in the ground owned by a liar”!

There exists a particular category of commodity company, however, which bucks the trend: the ‘royalty and streaming’ companies. By virtue of their ‘compounder-like' business models, these companies avoid much of the capital-intensive cyclicality that plagues other resource companies.

Royalty and streaming companies offer investors higher-quality and lower-risk exposure to the production of an underlying commodity. Such firms typically have high profit margins, strong cash flows and strong balance sheets.

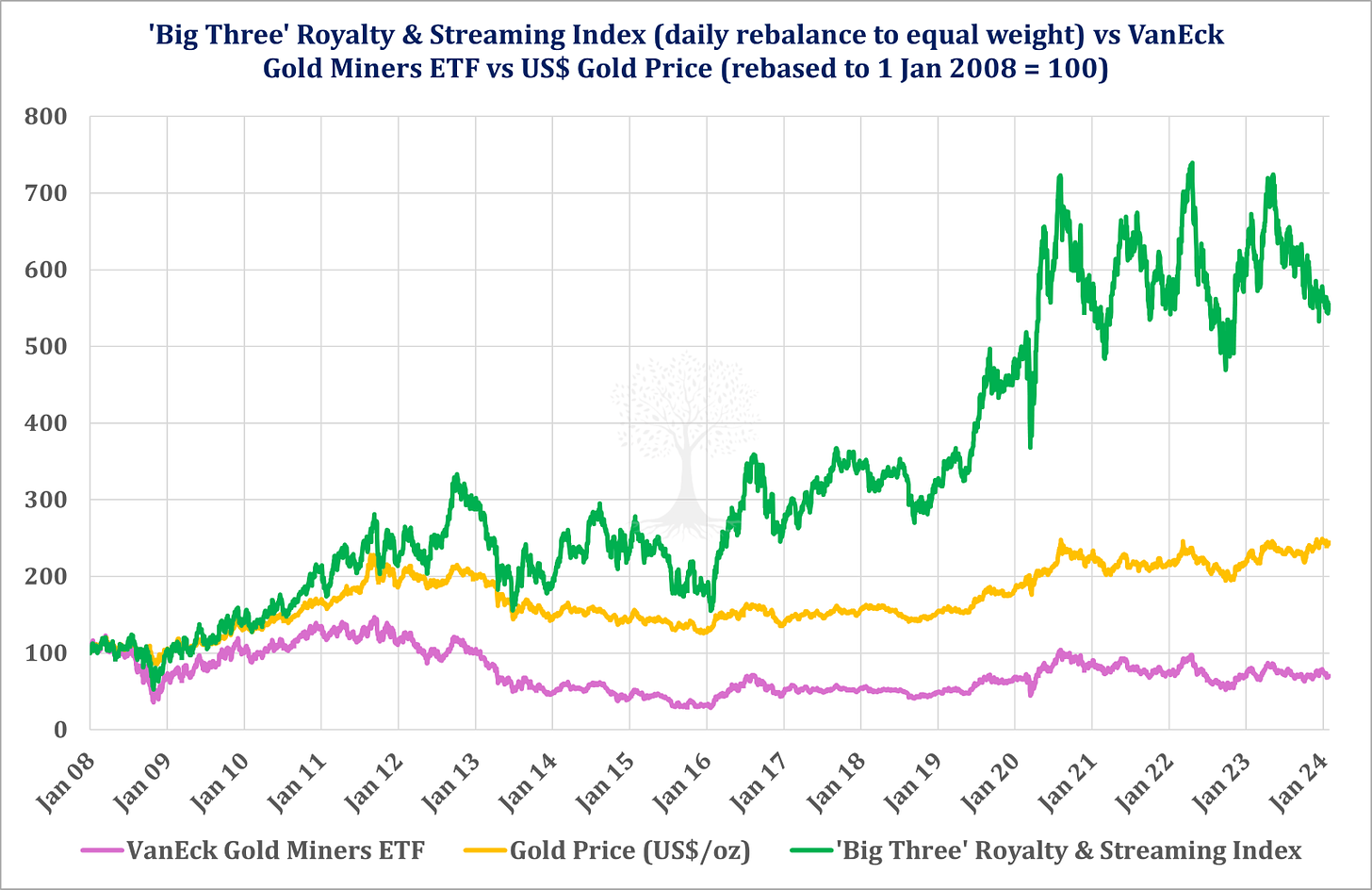

A commodity company with more leverage (financially and operationally), such as a miner, might well do better over a certain period when the price of a commodity is rising fast. Over the whole cycle, however, it is the established royalty and streaming companies which typically perform better than the commodity producers, with higher returns and less volatility in earnings and share prices.

So how do the royalty and streaming companies manage to perform such alchemy, turning cyclical and capital-intensive cash flow into something far more precious?

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The Power of Energy Royalties: Texas Pacific Land & the Emergence of the Royalty Model

The Origin of Precious Metals Royalties & Streams: Franco-Nevada & Silver Wheaton

Royalty & Streaming Companies: the Basics

Before we proceed any further, some definitions are in order – what exactly are ‘royalties’ and ‘streams’?

In a royalty deal, an investor typically makes an up-front payment to a commodity producer, usually to fund project development. In return, the investor receives a future share of the project revenue (i.e., the cash flows generated by selling the commodity). Note that a royalty investor receives cash, and does not receive delivery of any physical commodity.

In a streaming deal, a streamer makes an upfront payment to secure a share of a producer’s future commodity production at a predetermined, discounted price.1 In this case, the streamer typically makes an upfront payment and then will also make future payments-on-delivery when receiving the pre-agreed ‘stream’ of a physical commodity.2

While these business models seem clear enough, it is interesting to ponder why these companies came into existence and why their flavours of financing are in demand.

The average junior resources company is typically strapped for cash but is also desperate to explore and develop a new commodity project. In the unlikely scenario that the stock price of this junior is trading at a high valuation (i.e., a multiple of NAV), then it’s a fairly easy decision for management to issue new shares and use this equity capital to fund exploration and development.

More often, however, the share price of a junior is trading at more depressed levels (i.e., at a substantial discount to NAV). Instead of diluting shareholders (and insiders) by issuing new shares at a low valuation, it might make more sense to sell a royalty on the future production of a certain project and use this cash to fund exploration and development instead.

If this is the incentive for a resources company to sell a royalty claim, what are the benefits for a royalty investor?

Royalty companies offer investors two types of upside benefit: price optionality and land optionality.3

Price optionality refers to the fact that royalty companies have no meaningful operating expenses or holding costs. If the price of the underlying commodity goes up, or if production from the royalty project increases, then almost all of that additional income will be passed through to the profits of the royalty owner.

Land optionality refers to the tendency for resource owners to want to keep expanding the operation they have already built (by increasing production and doing more exploration). There are usually high capital requirements to establish a mine (or production from a reservoir), and it makes sense to keep this running for a long as possible, on as large a scale as possible, to maximise returns. Royalty owners are clear beneficiaries of this dynamic but do not have to make any additional investment themselves.

The motivation for streamers, on the other hand, is somewhat different. Streamers tend to focus on gaining access to commodity byproducts generated by a mining company which is focusing most of its efforts on mining another commodity.

For example, silver often coexists in gold, zinc, lead and copper deposits. Public market investors rarely attribute much value to the silver byproduct which may be found alongside the main deposit (e.g., copper or gold) which the miner is targeting. A streaming deal, however, can help to unlock in advance some of this silver byproduct value to help fund the development of the mine, thereby providing a valuable additional source of funding.

What are the benefits for a streaming investor? First, a streaming agreement allows the investor to focus on one commodity in particular, allowing more tailored commodity exposure relative to a royalty investor.

Similar to royalty investors, streaming investors benefit from price optionality, as the price of the commodity is ‘fixed’ in advance while the discounted payment for the commodity need only be made in the future. If the price of the commodity goes up, then almost all that additional income will be passed through the profits of the streamer.

Streaming investors also benefit from land optionality. Since streaming agreements are typically for the life of a mining operation, any successful mine exploration and expansion activities come at no additional cost to the streamer.

Finally, streaming investors are protected from any cost overruns and/or inflationary cost pressures.4

Fit for a Queen

The history of the 'royalty’ model is not new.

In 1567, an important lawsuit between Queen Elizabeth I of England and Thomas Percy, seventh Earl of Northumberland, was argued in front of a specially assembled high court. The issue at stake was who had the right to the gold byproduct which had been discovered on lands belonging to the Earl of Northumberland, at copper mines near Keswick in the Lake District.

The Earl of Northumberland argued that it was he who owned the gold, based on rights to the land granted to his ancestors by a previous monarch. Queen Elizabeth and her advisors, on the other hand, were keen to establish the Crown’s right to mine all gold and silver within the realm. After all, a renewed war with Spain seemed likely, and the realm was strapped for cash. The Earl had also not worked the mines in more than seventy years; the Crown argued that this meant he lost his rights to the gold.5

By 1568, unanimous judgment was reached in favour of the Queen:

“That by the law all mines of gold and silver within the realm, whether they be in the lands of the Queen, or of subjects, belong to the Queen by prerogative, with liberty to dig and carry away the ores thereof, and with other such incidents thereto as are necessary to be used for the getting of the ore.”

This judgment created an important precedent for defining royal privilege throughout much of the following century. It also clearly demonstrated that the right to mine gold and silver resided with the realm. Such ‘royal metals’ could be mined only if a payment was made to the Crown.

This idea of sovereign rights later also found its way into the Crown Charters granted to early American settlers, and “in practically all of them, a provision is made for reserving to the King a certain portion of the precious metals found”.6

It was these historical developments which laid the ground for the emergence of the royalty model as an ‘asset class’.

The Power of Energy Royalties: Texas Pacific Land & the Emergence of the Royalty Model

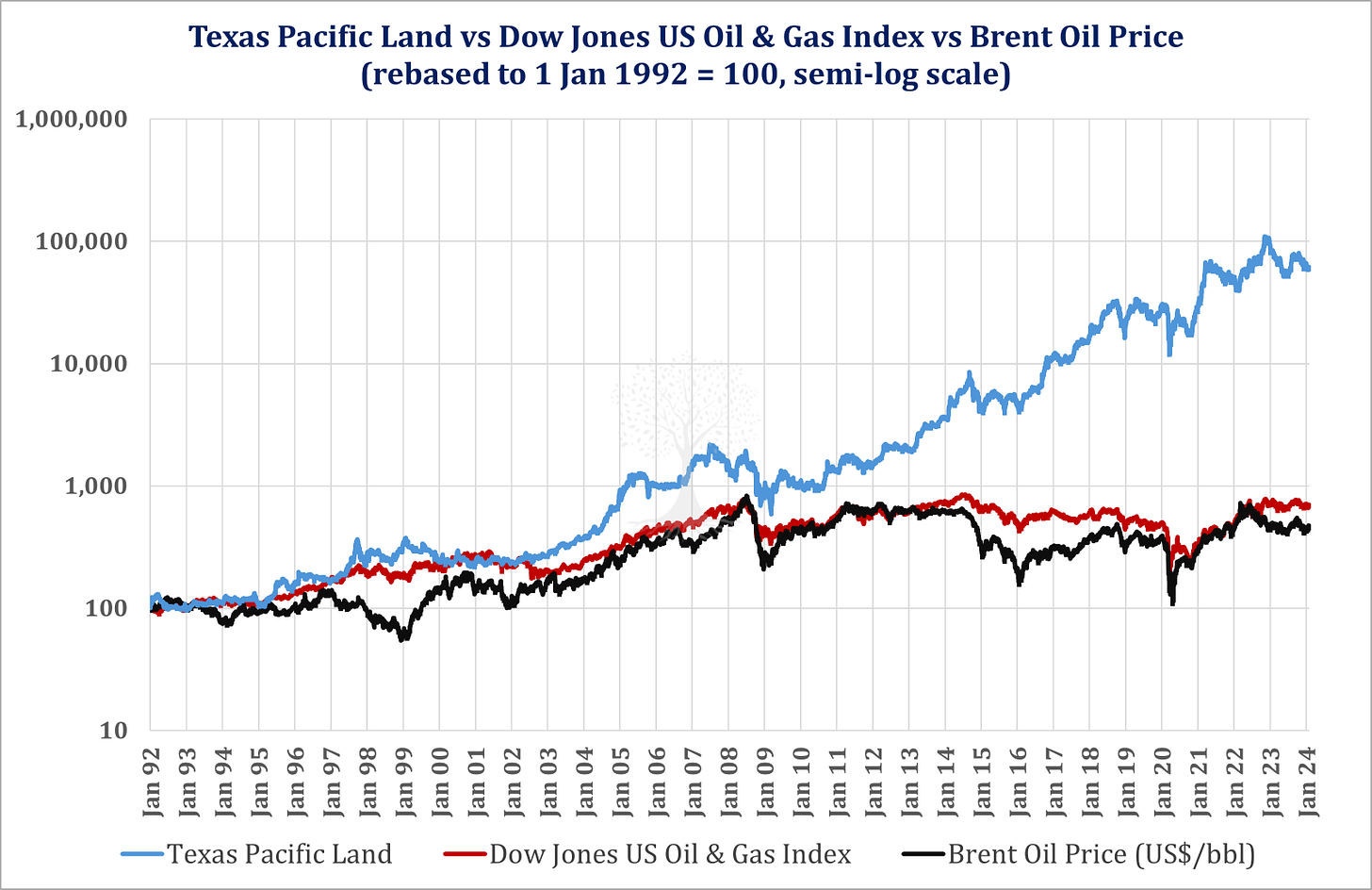

The first publicly listed royalty company was the Texas Pacific Land (‘TPL’) Trust. The Trust emerged out of the bankruptcy of the Texas and Pacific Railway Company in 1888, and Certificates in the Trust were eventually listed on the NYSE in 1927. Almost one century later, these certificates are still being traded on the stock exchange and the company controls 900,000 acres of land in the Lone Star State.7

In the United States, the law on land rights draws a distinction between ‘surface estates’ and ‘mineral estates’. Surface estate ownership is the right to build on the land, while mineral estate ownership is the perpetual right to develop and extract minerals located beneath the surface.

These two rights can be ‘severed’, meaning that landowners with no experience of mining or drilling for oil can lease out or sell the ‘mineral estate’ under their house to a resource company which wishes to extract the subsoil commodities. In this case, the resource company would typically pay an upfront lease bonus as well as a royalty (i.e., a percentage of production revenue) to the owners of the mineral estate in return for its use.

In the case of TPL, the mineral estate under TPL’s land was transferred to a new company called TXL Oil in 1954. This new company was then spun off and shares distributed to TPL shareholders. TXL Oil was later acquired by Texaco, which is now part of the Chevron Corporation.

TPL, however, retained surface ownership rights as well as ‘non-participating royalty interests’8 on certain tracts of land. The company continues to generate cash flows from these assets without any need to make further investments.

The advantages of a royalty ownership business model such as TPL’s are clear. Companies such as TPL have no direct exposure to the ongoing capital expenditures and operating expenses required for the extraction of a commodity. They also have no exposure to any abandonment or environmental liabilities.

Furthermore, royalty owners are the natural beneficiaries of any new discoveries on their lands, as well as advancements in technologies to exploit existing reserves which could not be extracted economically in the past. This is truly passive income!

The clear attractions of this business model have of course drawn others to the space. These days, the energy royalties’ market is the largest royalty market in the world. In the US alone, it has an estimated size of US ~$711bn.9 Most of this value is held by private companies, with only a single-digit percentage owned by publicly-listed firms.

We estimate that there are currently ~24 listed energy royalty companies in North America, representing US ~$36bn in market capitalisation. Energy, however, is not the only area where the royalty model has demonstrated its profit power.

The Origin of Precious Metals Royalties & Streams: Franco-Nevada & Silver Wheaton

Despite TPL’s long history as a listed company and massive success over this period (Figure 2.2), the royalty model only started to get more widespread attention from other commodity investors in the 1980s.

In 1983, Seymour Schulich and Pierre Lassonde famously founded the Franco-Nevada Corporation as the world’s first gold royalty company. They recognised that companies which embraced the oil & gas royalty model (including TPL) had some of the highest returns on capital in the resources world, and they sought to replicate this success with gold.

Their plan was to leverage their technical expertise and mining sector relationships to find private royalties on attractive deposits with good potential. Their first deal was in 1986 when they bought a royalty on the Goldstrike mine in the Carlin Trend (located in Nevada in the US) for a consideration of US $2mn. At the time, this was a small heap-leach mine and had a deposit with an estimated resource size of just ~500,000 oz.

Within a few years, American Barrick (now Barrick Gold) purchased the Goldstrike mine and increased their exploration activity. This eventually revealed an enormous ~50mn oz orebody which was to drive the success of both companies. Franco-Nevada’s initial investment has made a cash return of more than 500 times, with no follow-on investment required.

Using the proceeds from their initial successes, Franco-Nevada began acquiring royalties in many of the more prolific gold camps around the world, including the Carlin and Getchell trends in Nevada, Timmins and Kirkland Lake camps in Ontario, and the Kalgoorlie belt in Australia.10

Many of the existing third-party royalties acquired by Franco-Nevada were sourced from a wide range of previous owners, including individual prospectors, government agencies and other unlisted companies. The sellers were willing to part with the royalties because they often had little visibility on the development timeline of the mine, sometimes due to permitting and/or financing challenges.

Selling to a royalty company such as Franco-Nevada allowed these owners to cash out and deploy these funds elsewhere. Some of them chose to invest in Franco-Nevada shares, giving them access to a more diversified portfolio of royalty interests.

Key to Franco-Nevada’s success has been management’s relationship with the owners and operators of the projects. This allowed them to gauge the probability of monetising their royalty interests and the likely timeline for project development.

The next innovation in the precious metals royalty market came in 2004 with the invention of ‘streaming’. Wheaton River Minerals, a listed Canadian company and owner of a gold mine in Mexico, created a new subsidiary named Silver Wheaton with a specific purpose: to purchase the future silver production from its Luismin gold mine.

In return for a ‘stream’ of all the future silver byproduct from the mine, Silver Wheaton made an upfront payment (including shares in itself) and a promise of future additional cash on delivery for the silver byproduct. Silver Wheaton also listed separately on the TSX in late 2004. The next year, Wheaton River Minerals merged with Goldcorp Inc. In 2006, Goldcorp proceeded to reduce its Silver Wheaton stake to below 50%, finally selling out completely in 2008.

In the following years, Silver Wheaton solidified its leadership position as the world’s leading silver streamer by acquiring Silverstone Resources and adding a series of accretive projects, including silver byproducts from three prominent mines operated by Barrick Gold.

After diversifying into gold, the company was renamed Wheaton Precious Metals (‘WPM’) in 2017. In 2020, the company completed a secondary listing on the London Stock Exchange.

These days, WPM is among the top three royalty and streaming companies in the world, alongside Franco-Nevada (‘FNV’) and Royal Gold (‘RGLD’). Since listing on 14 July 2004 WPM has made total shareholder returns of +23.2% per annum, vs +16.5% for FNV and +12.2% for RGLD over the same period (Figure 2.1).

Royal Victims of Their Own Success

In recent years, the success of the pioneering royalty and streaming companies has attracted an increasing number of competitors. At present, there are ~20 listed precious metal royalty and streaming companies globally, representing US ~$58bn in market capitalisation. Most of them are based in North America with their projects scattered around the world.

The market has recognised the incredible success of the larger precious metals royalty and streaming companies such as Franco-Nevada (Figure 2.1), and these companies typically trade at punchy valuations (>2x NAV).

In other ways, however, it’s true to say that the pioneers in this sector have become victims of their own success!

First, they are faced with increased competition from ‘copycats’. This includes a long tail of mid- and small-cap pretenders who have been vying for the crown as the next big royalty and streaming player. Some of these smaller companies have been able to acquire attractive future royalties, but are challenged by a lack of near-term cash flow. Imitation by such smaller royalty companies may be the sincerest form of flattery, but it can also increase the costs of doing business for the behemoths in the sector if other smaller players are seeking to acquire the same projects. Consolidation seems likely to be one solution.

Second, the leaders in this sector have achieved such a large size that it has become difficult to find enough royalty acquisitions of a sufficient scale to move the needle and drive growth. This has pressured some of the larger precious metal royalty players to start acquiring royalties on other commodities, including energy and iron ore.

Not all commodities, however, are necessarily suited to the royalty model. Gold and oil & gas royalties work because these are commodities which can have large and long-life deposits, relatively homogenous ore bodies and transparent, market- and/or exchange-based pricing.

Some commodities – including iron ore, potash, uranium and copper – also make the 'royal cut’ and would appear appropriate targets for royalty investors. Indeed, there exist a few listed companies which own royalties on each of these commodities. The opportunity set, however, is small in size.

We are more sceptical, however, of royalties on other commodities where processing accounts for much of the value-add, and where off-market contracting makes price discovery more challenging in ‘emerging’ commodities such as lithium.11

Final Thoughts

Given the profit power of the royalty model, why hasn’t it attracted more attention from investors?

First, the model is not prevalent outside North America. In many countries, there are restrictions on ownership of land with mining potential; for the most part, it is only governments which are allowed to own land outright or hold royalties.

Second, although royalties are a large asset class, only a small portion are publicly traded. Energy (i.e., hydrocarbon) royalties dominate the listed space, but with the rise of the ESG movement, an increasing number of investors are restricted from investing freely in this area.

Third, many royalty and streaming companies tend to be lumped together as ‘comparable’, when there can be significant differences in business models and the nature of their royalty holdings.12

In recent years, the investment team has taken a close look at the listed royalty and streaming universe in order to identify the best opportunities available. The Panah Fund has invested in several companies in this sector. These are exposed to various commodities, including precious metals.

We believe these firms offer significant potential upside, but with the lowest risk available within the listed commodity space. This is because they are able to provide investors with some protection from the cost pressures and mismanagement which is rife within the resources sector.

Finally, these best-in-class royalty players are also in a powerful position to push best practice – from a sustainability perspective – to all the companies within their portfolio.

These are truly investments fit for royalty!

Thank you for reading.

Varun Dutt, Larry Hill, Andrew Limond

This predetermined price might be fixed, or it might be at a certain discount to a specified spot price for the commodity.

For more information on royalties and streaming, please refer to this McKinsey primer.

For more information on the concept of optionality, see this recent video interview with Pierre Lassonde, co-founder of Franco-Nevada Corporation.

For more information on the streaming model, please refer to this infographic from Wheaton Precious Metals.

The Earl of Northumberland did not last long after this judgment. In 1569, he helped launch a short-lived revolution against the crown (the ‘Rising in the North’), and was then captured. He was beheaded a few year later in 1572, an early example of what happens to those who fight the royalty model.

‘The History of Government Property in Minerals in the United States’ by Tobias Lewin, 1931.

The original TPL trust structure was converted to a C-Corporation in 2021. A more detailed history of the Texas Pacific Land Corporation is available here.

Unlike the owner of a mineral estate, the owner of a ‘non-participating royalty interest’ (‘NPRI’) has no right to negotiate leases and nor do they receive any lease benefits – they just receive royalty payments.

This estimate comes from the Kimbell Royalty Partners investor presentation for Winter 2023 (p.36). The estimate excludes excluding ‘overriding royalty interests’.

For more information on Franco-Nevada’s portfolio of royalties, please refer to the company’s asset handbook.

Royalties, a longstanding practice in the music world, have in recent years extended to other intangible assets such as pharmaceuticals and various forms of intellectual property, (a classic example being Michael Jordan’s legendary deal with Nike). Moreover, the investment landscape now includes some listed companies and trusts which focus on non-resource royalties. Delving into these entities, however, is beyond the scope of this note.

One important distinction here is between two main royalty types: Fee Mineral (Title) Interests (‘FMI’) and Gross Overriding Royalties (‘GORR’). FMI is effectively perpetual and does not expire, while a GORR is tied to the duration of an underlying lease or license. We consider the former ‘superior’ in quality to the latter given the difference in duration. Other forms of mineral interests and royalties are explained here.