The Death of Mean Reversion and the Case for 'Asia ex-China'

The Covid-19 melt-up, why mean reversion is currently not working for value investors, and a closer look at Asian inflows

This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

This Insight is an extract adapted from the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q3 2020.1

The extraordinary start to this new decade has led many investors to clutch at comparisons and reach for rationalisations.

An important observation early in the pandemic – which by now has already become a cliché – is that COVID-19 has ‘accelerated’ technological adoption and hastened the pace of other nascent trends. The future has been brought closer by several years in just a few short months.

Equity performance in 2020 would appear to firmly endorse this view. The rebound from the March low at first lifted all boats as central banks backstopped markets. Since June, however, it has been a handful of US tech behemoths and other ‘pandemic beneficiaries’ (mostly in the communications, healthcare and alternative energy sectors) which have driven markets higher.

In the US, the divergence between these winners and the losers, in sectors such as energy and banking, has been immense (Figure 1). This yawning jaw-shaped gap appears to be a fitting symbol of the widening gyre between the privileged ‘protected sectors’ where price discovery is suppressed, and the suffering of small businesses and jobs in the real economy.

In the equity markets, the pandemic has poured fuel on the flames of existing momentum trades. Many of the popular stocks of the last two years are also the pandemic beneficiaries of 2020 - these have overshot to the upside on a wave of liquidity and a powerful narrative.

While some of these stocks may well deserve such market accolades, others have not received any material boost to cash flows and the moves appear to have been driven by speculative excess.

The experiences of 2020 have thus compounded the anguish of traditional ‘value investors’, who have reportedly just experienced their worst ever decade of performance relative to growth (worse even than the Dotcom Bubble era).

A variety of factors are thought to be responsible for the underperformance of ‘value’: from ever looser monetary policy, to the rise of passive investing, to increasing industry concentration and the emergence of powerful monopolists (especially in the US).

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The Death of Mean Reversion?

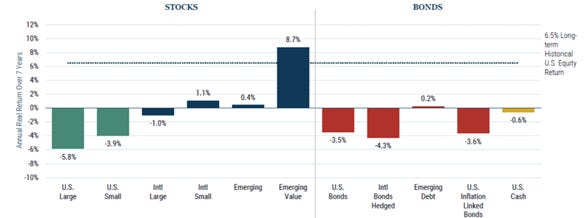

GMO, the respected investment firm, is known for its seven-year rolling asset class forecasts which are built on a mean reversion framework.

After many years of outperformance and high valuations for US stocks, GMO’s latest seven-year predicted annual returns (Figure 2) are now deeply negative (at -5.8% for US large caps and -3.9% for small caps). Indeed, the only asset class expected to have a significant positive annual real return over the next seven-year period is Emerging Market (‘EM’) value stocks (+8.7%).

If this were correct, surely investors should be tripping over one another in their rush to allocate capital towards EM value stocks?

This is not happening. Mean reversion-based forecast systems have been predicting weak US and strong EM returns for several years. During this time, the US has continued to outperform.

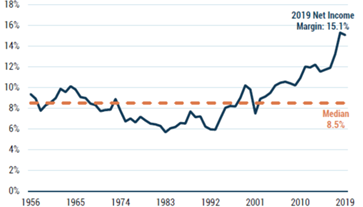

The ‘failure’ of mean reversion during this period is due to various factors. One of the most important reasons, however, is that profit margins in the US – which have increased to elevated levels relative to history – have remained stubbornly high (Figure 3).

In previous cycles, the profit margins of most firms rose and fell together with capacity utilisation. During the last decade, however, it has instead been a handful of mega caps (the ‘FAANGs’) which have continued to grow their margins – dragging up the average for the entire market – as they accumulated oligopolistic star power at the expense of the rest of the US corporate constellation.

How sustainable is this trend? With dominant market positions, low costs, and an ever-growing treasure trove of data, many see the position of the tech giants as unassailable. Indeed, it is well understood that tech is indispensable for firms in all sectors, and that almost all incremental revenue for a good software company falls directly to the bottom line.

Moreover, with interest rates in the US rates now near zero, some believe that it makes sense to pay much higher valuations for these stocks. Rather than owning bonds with a sub-1% yield, surely it makes more sense to own a dominant tech monopoly with a ~2% cash flow yield?

Valuations already reflect a rosy outlook, however, so investors would be wise to ask what might change.

The largest of the tech firms are increasingly attracting the attention of the antitrust authorities in the EU and the US. While the dominant market position of the tech giants might not change overnight, these companies now have targets on their backs as the Zeitgeist shifts to prioritise labour over capital. The recently launched US DoJ antitrust lawsuit against Google might well mark the opening battle in a war against big tech.

Given these concerns, some investors are already starting to bet on a rerating of cyclical stocks relative to tech, catalysed by an economic recovery on the back of a COVID-19 vaccine and a big post-election US stimulus package.

For those who prefer not to take such a binomial bet, however, does Asia provide a possible solution?

Asian Performance and Flows: China vs Asia ex-China

Those who follow the US more closely might be unaware that the situation in Asia markets is “same same, but different”.

The overwhelming Asian sector losers so far in 2020 have been energy, industrials, financials and utilities, while the winners have been IT, healthcare and consumer stocks. The Asian country losers this year have been in Southeast Asia (Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines and Singapore),2 while the winners have been in north Asia (China, Taiwan and Korea).

This pattern of performance mimics the previous decade, with Indian equity markets as the exception. (Indian stocks enjoyed a strong decade in the 2010s, but have underperformed so far in 2020 as the country was hit by COVID-19 on top of a growth slowdown and a banking crisis.)

Astute observers will also note that there is a positive correlation between the weighting of ‘tech’ stocks in the country indices and positive country performance in 2020.

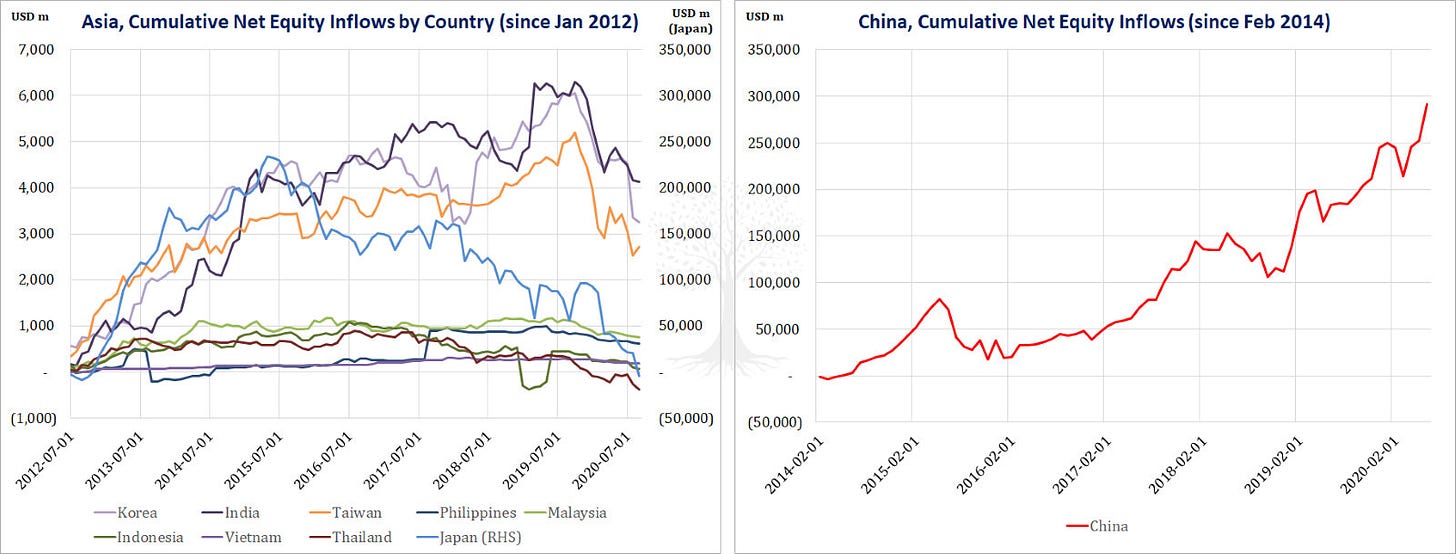

In past letters we have discussed the extraordinary outperformance of US Dollar-denominated assets over the last decade: bonds, equities and the currency alike. The flip side of this phenomenon has been the massive sucking sound as capital has drained out of most Asian equity markets (Figures 4.1-4.2).

All Southeast Asian markets (with the exception of Vietnam) have seen persistent outflows for the last seven years, especially since the start of 2018. Even Japan has now lost all of the foreign inflows which initially entered during a 30-month period after the launch of Abenomics in December 2012. Over the last eight years, just a handful of Asian equity markets have seen meagre net inflows, namely India, South Korea and Taiwan (Figure 4.1).

The exception is China (Figure 4.2). Other Asian equity flows pale into insignificance compared to this market, which has attracted massive inflows since 2014 as rules for inbound investment flows have been relaxed. (Note the 50-factor y-axis scale difference for China and Japan vs other Asian markets.)

Even in Asia, investors are thus facing the same sort of bifurcated market that exists elsewhere in the world. It is notable that the current elevated valuations of Chinese blue-chip tech and consumer names are similar to their counterparts in the US.

The market appears to be expecting that even as Sino-US tensions increase, US and China technology companies will dominate the rest of the world in the 2020s, thus allowing valuation disparities to persist over time.

While foreign investors appear to be increasingly fixated on crowded Chinese tech and consumer stocks, however, we believe that it makes sense for all investors to have a strategy for Asia ex-China.

As capital has gushed out of the region, opportunities have emerged. We believe that stock-picking in out-of-favour Asian sectors and countries might well make for attractive investment returns in the coming decade as capital trickles back to the region.

Thank you for reading.

Andrew Limond

The original source material has been edited for spelling, punctuation, grammar and clarity. Photographs, illustrations, diagrams and references have been updated to ensure relevance. Copies of the original quarterly letter source material are available to investors on request.

The only reason that the Malaysian index has escaped worse performance so far in 2020 is because of the extraordinary pandemic-induced performance of the rubber gloves stocks.