The Investment Case for Vietnam

Vietnam as the new export-manufacturing 'Asian Tiger', the challenges of investing in the country, and a case study of a Vietnamese jewellery company

This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

This Insight is an extract adapted from the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q2 2016.1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The essential thrust of the Vietnam macro story which we described in our letter one year ago has not changed.2 Having emerged from a classic credit bust of its own making at the end of the last decade, Vietnam is at the beginning of the end of a bank recapitalisation process.

After several false starts over the last two decades, in our view Vietnam now stands a very good chance of being the next Asian country to modernise by following the tried-and-tested export-manufacturing growth model.

With a favourable location just to the south of China, Vietnam is relatively easy to integrate into global supply chains. Vietnam has reasonably good infrastructure, favourable demographics and cheap labour costs (with factory wages less than one quarter of the level of China).

Vietnam is well placed to capture market share in low-end manufacturing. The country is growing its textile industry fast, but there is also rapid expansion in processed electronics manufacturing, and good potential for oil and gas-related industries to flourish. With sensible policy decisions, there is the potential to move up the value chain over time.

Critically, government policy is now supportive of foreign investment, and in recent years there has been a build-out of industrial estate zones in the north and south of the country. The government is providing tax breaks to attract investment, and it is unsurprising that inbound FDI has started to accelerate in recent years. Vietnam has signed various trade treaties3 over the last decade, and merchandise exports have been growing at a rapid clip.

In portfolio terms, an allocation to a ‘frontier market’ is usually harder to manage than an allocation to a developed market. Liquidity is typically poor, and it is also difficult (if not impossible) to hedge exposure by shorting individual stocks, index futures or the currency.

In Vietnam, it is not possible to short stocks onshore, though offshore investment banks allow some stock-shorting through expensive swaps. There are no index futures in Vietnam, although it is possible to borrow and short some of the offshore-listed Vietnam ETFs in modest size.

Non-Deliverable Forwards on the Vietnam Dong (VND) do exist and have been actively traded at various points in the past. In practice, however, nobody is currently prepared to take the other side of the trade, rendering it effectively impossible to hedge VND exposure.

All of this means that one had better be confident not just in the companies in which one is investing, but also in the stability of the currency.

Confidence in the Currency and Vietnam’s Potential Path for Growth

Memories of sharp currency depreciation in the Vietnam Dong in the three years following the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 are still fresh. Indeed, investors always seem to remember the last crisis most vividly, and when investment strategists enumerate the risks of investing in Vietnam, an unstable currency always seems to be near the top of the list.

Around one-third of the Panah Fund is exposed to the Vietnamese currency through the fund’s equity investments in the country. Despite widespread concern about future potential depreciation of the Vietnam Dong, we have been unable to find any thorough research on the currency. We thus recently took the decision to commission an independent research report on Vietnam’s currency and economy from Redward Associates.4 The key findings of this report are summarised below:

Depreciation of the Vietnam Dong against the US Dollar is not pre-ordained.

Vietnam’s extremely low level of GDP/capita (1/25th of the US at market prices and 1/9th of the US at purchasing power parity) is consistent with a very low exchange rate on a real effective exchange rate basis. However, as Vietnam opens its economy to foreign trade and capital flows, we are likely to see a continuation of the trend appreciation in the real value of the VND (the VND has appreciated at an annualised pace of ~3.4% since 2004, though has depreciated on a nominal basis over this period owing to bouts of rapid inflation).

The primary source of pressure on the VND over the past decade has been high and unstable inflation leading to a loss of competitiveness, instability in the balance of payments, loss of reserves, and currency depreciation. To the extent that the State Bank of Vietnam (‘SBV’) can stabilise inflation, this source of instability can dissipate.

Indeed, if the SBV were successful in stabilising low inflation and the USD were to resume its long-term downtrend, we could see a sharp improvement in the balance of payments and appreciation pressure as observed in China during the 2002-14 period.

In the near-term, we judge that the risks to the VND are primarily external: a strengthening US Dollar and/or a rapidly weakening Chinese Yuan triggering broader ‘risk-off’ sentiment. As these risks are primarily external, we think that some of the risks to the portfolio associated with our Vietnam exposure can be hedged in currencies other than the Vietnamese Dong.

In many ways, the similarities to China at the start of the millennium are uncanny, not just in terms of the FDI and trade opportunity, but also in terms of the likely path of urbanisation:

“The combination of access to developed markets, access to foreign technology and capital in the form of both FDI and portfolio capital, and a relatively stable macro-economic environment is encouraging Vietnam to follow the development path of previous ‘Tiger Economies’ of East Asia, utilising its basic resource: labour. With GDP/capita at market prices just US $2,321 and only 30.5 million (33%) of the population urbanised, we see ample scope for Vietnam to draw labour into the market economy and raise labour productivity. Assuming that the Authorities maintain their outward-oriented policy stance, we see little reason why Vietnam can’t sustain its current pace of GDP growth for up to a generation. Indeed, our back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that if it were to sustain 5.5% potential GDP growth for 25 years, GDP/capita at market prices would rise to around USD 25,000, bringing Vietnam into the middle-income bracket.”5

This is clearly an optimistic long-term scenario, and it requires a lot to go right for this to play out as described over the next 25 years.

A stable external environment (especially for international trade) would be helpful, though currently this is by no means assured. Vietnam’s politicians will have to continue to embrace the outside world in order to continue to attract foreign investment. Inbound investment is currently dominated by FDI into the manufacturing sector, although one would hope that over time, FDI to the retail sector as well as portfolio flows should also increase.

The government could be doing more to facilitate investment from abroad. Foreign Ownership Limits (‘FOLs’) for domestically-listed stocks are slowly being lifted, though we would also like to see an acceleration of the State-Owned Enterprise (‘SOE’) privatisation process, which to date has disappointed owing to resistance from entrenched political players and vested interests.

A more comprehensive SOE-privatisation process would not only attract know-how from abroad and from the private sector, but it would also ease concerns over Vietnam’s fiscal deficit (equivalent to -5.9% of GDP in 2015, with debt-to-GDP at 58.3%).

Widening the tax base to boost fiscal income would be healthy, as it would create more room for development expenditure. It would also be helpful to see greater efforts to combat corruption and waste on the expenditure side.

Keeping inflation in check will be a vital task: “In the past, the SBV’s policy of stabilising the VND has been associated with ‘hot money’ inflows, upward pressure on reserves and problems with sterilisation, leading to inflation.”6 Indeed, going forward, the SBV will have to embrace more competent and flexible policymaking, preferably with a focus on price stability (and with more exchange rate flexibility).

An ability to sustain financial stability will also be vital in order to maintain credibility. Two near-term ‘tests’ are the ongoing bank recapitalisation process and the real estate market. The property market has rebounded fast from the crisis, with activity and prices recently becoming slightly ‘frothy’ in certain locations (for instance the condominium market in Ho Chi Minh City).

Corporate Governance Considerations

For investors in the Vietnam equity market, corporate governance is a constant concern. Nevertheless, thanks to patience and diligence from several local and foreign investment firms, we are quietly optimistic that this is improving. As always, it pays to choose your investments carefully.

The Vietnam Accounting Standards (‘VAS’), while based on International Financial Reporting Standards (‘IFRS’), have their own unique features.7 Convergence is expected over time, though this is not likely to happen fast. While local investors tend to react to published quarterly EPS numbers, it is necessary for longer-term investors to make frequent and sometimes quite substantial adjustments in order to get closer to a ‘core earnings’ or ‘core cash-flow’ number. This can lead to opportunities as well as frustrations.

One common accounting item in Vietnam is the contribution to the ‘Bonus and Welfare’ (‘B&W’) fund, which tends to be reported below-the-line on the income statement (while the fund balance itself is reported as a liability on the balance sheet). In theory, this is a ‘slush fund’ which contributes to employees’ weddings, medical care and funerals. In reality, though, there is often little transparency over how the money is spent.

In certain cases – even for the largest and best-known Vietnam companies – this contribution to the B&W fund (and indeed the drawdown from the fund in any given year) can be as large as 20% of net income. When working out a firm’s ‘earnings power’, a conservative investor might choose to include the B&W fund drawdown for any given year in the company’s operating costs, thereby reducing net income.

One of the more vexing trends in Vietnam in recent years, which has unfortunately become quite fashionable, is for companies to implement increasingly aggressive ‘Employee Stock Ownership Plans’ (‘ESOPs’).8

Panah tends to encourage equity participation for the top management of portfolio companies to give them ‘skin-in-the-game’, although there are more and less appropriate ways to achieve this end. We do not object to ESOPs issued in modest size, with an exercise price close to (and preferably above) the market price, using a long vesting period, awarded to managers who can really have a direct positive impact on the share price over time.9

We struggle, however, to justify ‘ESOPs’ which involve the immediate issuance of ~5% of outstanding shares, at ‘par value’ or below (i.e., typically a large discount to market, of >50% or more), and with short or no vesting periods.

While some investors might find this tolerable as a one-off event for a growth company where management does not yet have any share ownership (e.g., a former SOE which is now run by more entrepreneurial management), it certainly becomes less forgivable when this exercise is repeated on an annual or biannual basis. Sadly, this is fairly common in Vietnam, even among some of the largest and most well-known companies in the market. In several cases, we think this behaviour has even been tantamount to theft from minority shareholders, and all too often they acquiesce!

Conversations with management who implement these discount ESOPs have been instructive. While some managers are clearly aware of the impact of the actions, and know that under IFRS their ESOP schemes would likely have the effect of ‘wiping out’ even as much as two-thirds of earnings in each year that the ESOP is issued, other companies are not quite so savvy on the accounting impact. In some cases, it is true that management do have more admirable motives, for instance to spread more wealth among their employees, even on the factory-floor.

For companies with management and boards who have a more limited understanding of the impact of ESOPs, we attempt to try to engage to explain the effect of their actions, including the dilution effect over time. We also attempt to explore alternatives.

We prefer to avoid completely, however, the shares of companies – even hot growth stocks! – where senior management appear to be acting more cynically. In our view, these managers have given us fair warning that they prioritise their own interests over those of minority shareholders. There is no reason to think that will change in the future.

Despite the challenges, we nevertheless believe that we have managed to find several attractive investment opportunities in Vietnam. We share a case study in this letter, and plan to share more case studies in the future.

Case Study: Vietnamese Jewellery Company (Current Market Cap US $340mn)

Panah has recently established an interest in the dominant jewellery retailer in Vietnam.

Back in 2011, ~70% of this company’s revenues were generated by the sale of gold bullion bars. During the course of Vietnam’s unsettled and occasionally inflationary history, physical gold has been seen as an attractive store of wealth.

Over the last five years, the company has gradually transformed itself into the country’s leading jewellery firm. This commenced with wholesale, and more recently the company has become a dominant jewellery retailer with more than 200 stores around the country and an estimated market share of ~25%. (The nearest competitor has just 36 stores; most jewellery retailers in Vietnam are still ‘mom-and-pop’ stores.)

In 2015, almost 80% of the company’s revenues were generated by jewellery sales (of gold, gem-set and silver jewellery), most of which were retail sales with gross margins in the mid-20% range (wholesale generates margins of just 3-4%). While low margin gold bullion bar sales continue, margins are extremely low, and the real value of this activity now is that it gives jewellery customers confidence in product quality (as this is one of the few firms still allowed to deal in bullion).

The company has worked hard to upgrade its jewellery design, and has also modernised its stores to offer a much more pleasurable retail experience than was the case even as recently as ~18 months ago. The company continues to gain market share, with same-store-sales growth running in the mid-teens, and store rollouts continuing around the country.

On top of this sales growth, over time we expect that the company’s mix of bullion and wholesale will fall further as jewellery sales accelerate, thus driving margins and profits higher. Barring external shocks, we conservatively estimate profit growth of 15-20% per annum for the next five years, and are cautiously optimistic that the firm should be able to generate such growth even further into the future.

The company’s transformation from bullion dealer to committed jewellery retailer has not been an easy process. Over the years, management had built up various non-core investments in diverse areas such as fuel stations, banking and real estate.

The husband of the jewellery firm’s chairwoman used to serve as the CEO of a bank which provided gold-denominated loans to fund the firm’s working capital needs. Unfortunately, this business relationship also prompted the jewellery firm to take a substantial equity stake in the bank. The bank got into trouble and racked up a substantial amount of non-performing loans (following Vietnam’s real estate bust), and was finally placed under special supervision by the State Bank of Vietnam in the middle of 2015.

The stock market quickly worked out that this would mean that the jewellery company would need to make a substantial write-down on its bank stake (and a related real estate holdings). The share price tumbled by ~25% during the summer last year as investors dumped the stock.

We looked at the numbers and judged that it was an overreaction. Looking through the one-off hit to earnings from the write-down, we estimated that the jewellery company’s share price had fallen to a multiple of just 8x 2015 core earnings after tax.10

The negative market sentiment thus presented nimble investors with the opportunity to establish a position in this fast-growing retail franchise at a reasonable valuation. It was also reassuring that company management committed to divest or to make complete provisions for all non-core investments, a process which is now almost complete.

The share price of the company has more than doubled since the lows of the summer last year.

Thank you for reading.

Andrew Limond

The original source material has been edited for spelling, punctuation, grammar and clarity. Photographs, illustrations, diagrams and references have been updated to ensure relevance. Copies of the original quarterly letter source material are available to investors on request.

For more information, see the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q2 2015, as well as the following Seraya Insight: ‘Vietnam: from Frontier to Emerging Market?’.

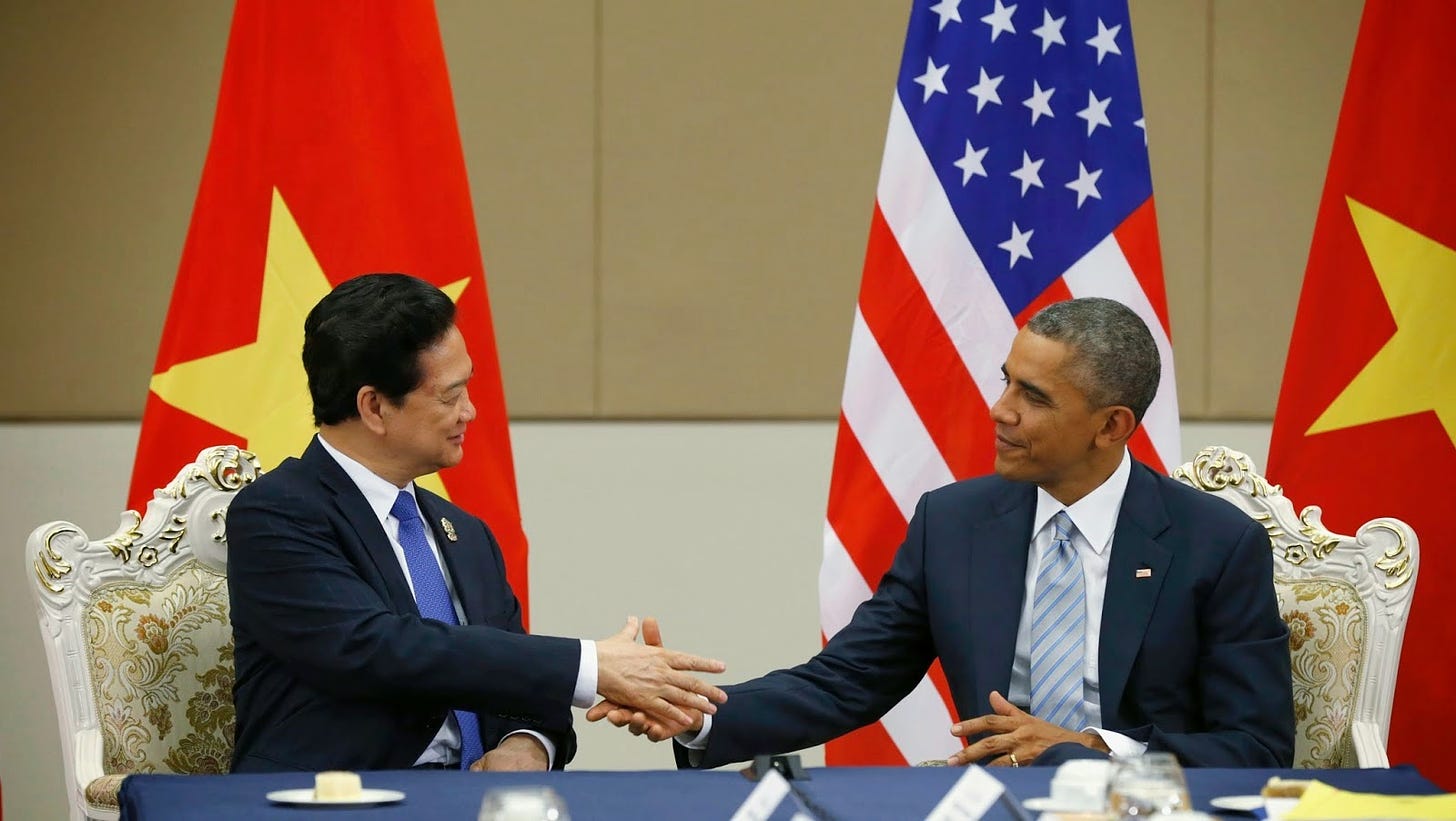

Vietnam joined the WTO in January 2007, and followed this up with an Economic Partnership Agreement with Japan in October 2009. The Korea-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement was agreed in December 2015. In the same month, Vietnam and the EU agreed a bilateral trade treaty; this is now awaiting ratification and implementation is expected in 2018. Vietnam recently also negotiated entry into the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Given worldwide tensions over trade and globalisation, it is uncertain whether this treaty will be ratified in the United States and other countries. However, a recent state visit by US President Obama to Vietnam hints that no matter whether the TPP is enacted, Vietnam will continue to build out its commercial and political ties to the US.

Redward Associates provides independent research into the forex markets of Emerging Asia. The principal of the company is Peter Redward, an economist with extensive experience who has been researching Asia-Pacific economies and currencies since the 1990s. The full report is available to shareholders of the Panah Fund on request.

Extract from Redward Associates report on Vietnam.

Extract from Redward Associates report on Vietnam.

A brief summary can be found here: http://www.vietnam-briefing.com/news/ifrs-vas-part-1-introduction-vietnamese-accounting-standards.html/.

One of the reasons for the popularity of ESOPs is that it brings tax benefits for the recipients.

For middle managers with more limited responsibility, rather than share awards, we favour cash bonuses when specific job-related targets are exceeded.